Leila Mottley Wonders If You Can Truly Write a Place You’ve Never Been

Creating an Authentic World Without Living in It

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

I’ve always been obsessed with Google Maps, specifically street view, but even more so since becoming a novelist. I have spent countless hours cruising down open highways on “Driving Through” YouTube videos and looking at the 360 view of a dead end street on Google Earth, memorizing street names, and getting to know a place from the comfort of my computer to include a new setting in a short story or describe a character’s hometown. So when I decided to set my sophomore novel in Florida, I believed I could depict it using a thorough expedition on Google Maps and a library’s worth of travel books. Only when I actually began writing did I realize I was in over my head.

I knew the book had to be set in Florida before I wrote the first word. It was the only place in the country that could perfectly mirror the themes of the book, while simultaneously providing a vivid and beautiful Southern setting in a state where access to abortion was severely restricted. This was going to be a book about young mothers who are rarely viewed in their complexity, without judgement or shame, and it would be set in a part of Florida that is neglected, misunderstood, and complicated.

Florida is a state of paradoxes, from its history of colonization and relationship to enslavement, to its immigrant communities and conservative politics, to its gorgeous waters and swampy inlands. Young mothers are also living among the dissonance of teenage girlhood and parenthood, subject to the joys and challenges of both, and often misrepresented and othered because of it. The only problem was that I’d never set foot in Northwest Florida.

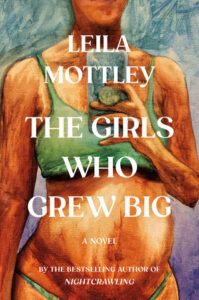

As soon as I made the decision to set The Girls Who Grew Big in the Florida Panhandle, I dove into research, exploring the Forgotten Coast, the emerald waters, the many poor small towns and the larger beach destinations. I tried to understand the geography through books and Google Maps and travel blogs. I tried to learn the language, the particular southern twang, through internet forums and interviews and YouTubers. But no matter how much I made use of the resources I had from my Oakland apartment, I couldn’t quite get there.

I believe it is part of the job of the writer to imagine beyond ourselves. I also believe there are limitations to what we can know without living, at least tangentially. Toni Morrison said in an interview with NEA that she told her students at Princeton to stop only writing what they know because they don’t know anything and she wanted them to stop “record[ing] and editorializ[ing]” and instead “imagine it, create it.” The advice to write what you know is in conflict with the very purpose of fiction. When we restrict ourselves solely to what we believe we know, we stifle our imaginations and prevent ourselves from the hard work of becoming, creating, and envisioning something far wider than the sliver of knowledge we have access to.

However, we also have a responsibility as writers to do our due diligence. Not to take the easy way out, to assume we know something because we have been exposed to it, or researched it, or heard about it. Particularly when we think about writing about other places, other cultures, other communities, we have to assume there is a wealth of experience so far out of our reach we don’t even know what questions to ask. We have to assume we will not get all the way there and be prepared to remain accountable for our shortcomings. At the same time, we have to do extensive work to get as close as we can and be willing to abandon the project if we see or believe the distance is too vast. When we are lazy in our imaginings and in our process of achieving authenticity, we can do more harm than good.

I have found it to be impossible to skillfully write about a place I’ve never been. I wrote the first half of The Girls Who Grew Big before I’d been to the Florida Panhandle. I figured that because I’d been to Miami and Georgia and had spent so much time researching, I could capture the place without seeing it myself. But draft after draft, my renderings fell flat. The water was vaguely green, the sand nothing but sand, the roads indistinguishable from any other road. I decided to write about a fictional town in the Panhandle and believed that would give me enough jurisdiction to bend reality and create new geographical ties, but my imagination struggled to know what I was looking for, what stores would be in the strip mall, how people walked, what people wore, the exact height and feel of the sand dunes. So I booked a trip.

The advice to write what you know is in conflict with the very purpose of fiction. When we restrict ourselves solely to what we believe we know, we stifle our imaginations and prevent ourselves from the hard work of becoming, creating, and envisioning something far wider than the sliver of knowledge we have access to.

I spent a few days in the Florida Panhandle with a camera and a rental car and no plan. I was not prepared for how wrong I’d been. Not that the descriptions in the early drafts were inaccurate, but that they were fractional and nonspecific, unable to draw upon the regional lilt of these peoples’ voices, the scents of the ocean mixed with sunscreen and gasoline from the dozens of pickup trucks in a beach parking lot, the way the place seemed to be stuck in the early 2000s in wardrobe and storefronts and Wi-Fi access.

I could not have understood the grit or the creatures or the endlessness of the sky without seeing it for myself. I spent days driving and walking and overhearing people talking at beaches and restaurants and even the middle of the swampy forest where I ran into a black man in jeans who told me to be careful of snakes and then continued on his walk in the woods. I wrote pages of notes, recorded the sound of the waves, took hundreds of pictures, and when I returned home, I brought it to life.

Suddenly, the book had color and sound and taste. It was no longer mine, because it could no longer understand only the things I had references for. My imagination had to grow. I had to see this place, feel it, hear it in order to have the framework to imagine these characters lives. I would not have the lived experience of being from there, living for years among the people I was writing about, but I knew I was as close as I could get.

I had created a Florida Panhandle that was intimate, rich in life, easy to touch, full of compassion and a genuine admiration, and I had assembled a world that could accurately and compassionately hold the story I was telling. Ultimately, this novel was about young motherhood in a sliver of Florida we rarely think about as anything but a Spring Break destination and it deserved to be written as a tangible, vivid, contradictory place where these girls are faced with challenges and decide whether to sink or swim.

_____________________________________

The Girls Who Grew Big by Leila Mottley is available via Knopf.

Leila Mottley

Leila Mottley is the author of the novel Nightcrawling, an Oprah’s Book Club pick and New York Times bestseller, and the poetry collection woke up no light. She is also the 2018 Oakland Youth Poet Laureate. She was born and raised in Oakland, where she continues to live.