Leila Aboulela on the Coups in Africa

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

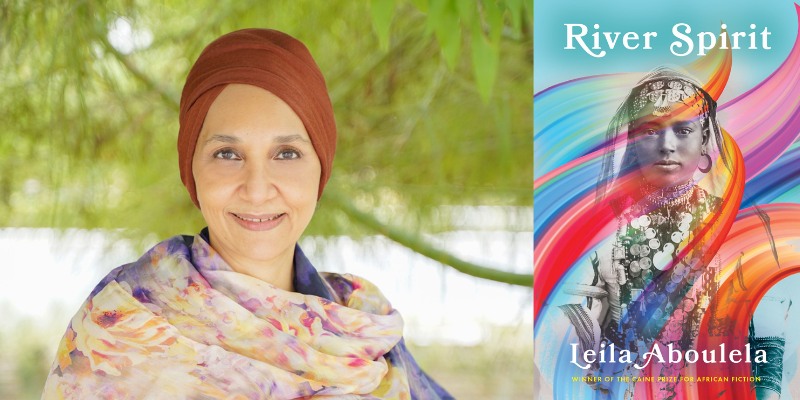

Novelist Leila Aboulela joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on their 200th episode to talk about the fighting between rival military factions in her native Sudan, which has displaced millions of civilians. She compares the situation of Sudan, which underwent a coup in 2019, with the six other African countries that have experienced coups since 2020. Aboulela explains the historical precedents and particularities and reflects on how, when a country’s military is its mightiest institution, a coup can be the only way to change leadership. She also reads from her new novel River Spirit, which covers the period of time leading up to the British occupation of Sudan.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: This year, conflict between rival factions of Sudan’s military government has led to fighting that has prompted, unfortunately, millions of people to leave their homes. You spent most of your childhood in Khartoum. This must be hard to watch. How are your friends and family there faring? And what is the situation like on the ground for civilians from the reports you’ve been hearing?

Leila Aboulela: I spent more than my childhood in Khartoum—I actually left in my mid-20s. And I had already graduated from university and got married and had a baby. So I did a lot of life there. My friends and my cousins, most of them, by day 11 of this conflict, had left the country. The first instinct of people was just to get away from this sudden, unprecedented bombing of their homes. And after they left for Egypt and other neighboring countries, things are very bad now for civilians, because this war has indiscriminately targeted hospitals, it’s bombed the airport, it’s bombed schools, water facilities, electrical supplies. So day to day life is just unbearable at the moment, and that’s why people have fled.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So they went to Egypt. Sudan borders, I think, seven other countries. I know there’s a lot of people who are internally displaced, and also people going into other countries. So your friends and family went to Egypt. Are there places within the country that are turning into refuges as well?

LA: Most people went outside the capital, they went to the provinces, which had less fighting. And they felt safer there. It just happened that my family and the people I know went to Egypt. I guess because we originally have ancestors from Egypt. So there’s always been a connection with Egypt. So the instinct was to go there as a place of safety. But people have gone to Ethiopia, Chad, South Sudan, depending on where they have links, where they have family members, but most of the displacement is happening within the country itself.

VVG: At the top of the show, we were talking a little bit about how I know someone in Egypt who has been working with people displaced from Sudan. And I was also reading a story in the Times about people who had gone from South Sudan, to Sudan, and were now returning, so doubly displaced. And I think that history of multiple displacements seems to be part of the larger story of the politics of this area. So Sudan became independent in 1955. And I was reading that since then, there have been 15 coup attempts in Sudan, five of which have been successful. Can you talk a little bit about how General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan came to power in 2019 and why he is now at odds with Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan, who is the leader of the paramilitary force, the Rapid Support Forces?

LA: Yeah, he came into power as a result of a civilian revolution against the old general, the old military dictator. So Sudan, almost from independence, with very few and short exceptions, has been ruled by one military dictator after the other, so really the army is the most powerful institution in the country. It’s got the biggest share of the budget. It’s the richest institution, it’s the most powerful institution in the country. So basically, just changing whoever’s ruling comes then with a coup, one coup after the other.

And so this General Burhan took over with a coup, but he was supported by this paramilitary, the Dagalo, that you mentioned. But then they fell out because this paramilitary was meant to be incorporated into the main army. But they negotiated the terms into which they would be incorporated in the country’s army, but they weren’t happy with the negotiations. And so they went to war in the capital, disregarding the people who were present. So that is what happened, unfortunately. And unfortunately, the paramilitary were encouraged and in the hope that they would lessen the power of the military. But it just backfired. It was just not a good idea. In theory, maybe it was a good idea. But in practice, it was just a disaster.

WT: Seems a little bit like the issues that Russia has been having with General Prigozhin, who runs a paramilitary organization there, as we all know, and he’s now dead. The Wagner group that became powerful then turned on the military itself. And there’s this infighting in that way. And both of these generals that we were speaking of played a role in an earlier conflict in Darfur. I wondered if you could talk about that and how that contributes to their history.

LA: Yeah, so this Hamdam Dagalo was a warlord in Darfur, and all these atrocities that were taking place in the capital [now] took place in Darfur. And he’s a warlord and he owns a lot of mines and gold and you know, he’s quite a powerful person in the west part of the country. And actually, people in Darfur are saying now to the people in Khartoum, well, you’re just tasting what we had before, the war has come to you in the capital. You used to be safe in your bubble. But now, the war has reached you as well.

WT: Sudan was a British colony. Earlier in the episode Sugi mentioned six African countries where there have been coups. Guinea, Niger, Chad, Gabon, Burkina Faso and Mali. These are all former French colonies. Of course, they all have their own specific political context. But what role does colonialism play in what’s happening here?

LA: Well, colonialism laid down the boundaries—the maps of all these countries—in ways which the colonialists thought was logical, but it might not have been logical for the people, and the way they were affiliated with their tribes and how they felt that they were loyal. But then colonialism decided to mark “this is Sudan, this is Chad, this is Guinea.” So that is one thing you’ve got, you’ve got a boundary, which is European-created. That is one thing.

And then the other thing is the way the colonialists did the divide and rule and how they kind of would set one group against the other and play one group against the other. And so this created these kinds of divisions and the separate development in certain areas of the countries and how perhaps one tribe would be elevated and be favorites amongst the British and be given land and be given help, whereas others won’t, because they’re deemed to be a threat. So these kinds of divisions and all of that, this is what the legacy is of colonialism, I would say. But I know at the end of the day, we’ve been independent for all these years, we can’t blame colonialism for every fault. We have to, as Sudanese, shoulder the good part of the blame.

WT: To what extent—this is just a thought experiment, you can tell me if this is completely nuts, but—you know, sometimes there are patterns. For instance, in the United States there’ll be clusters of mass shootings, right. If something bad happens, you give someone else an idea to do the same thing. And I wonder if—is it possible that because one state has a coup and then some other group thinks, “oh, we could do that in our country,” could that be contributing to the reasons why this number of coups are happening at this particular time, or are they all individually oriented and there’s no connection between them?

LA: It could also be to do with the flow of the firepower, you know, the guns, the weapons, the defense. The defense industry is very secretive, we never hear about unemployment in the defense sector, or how much sectors are earning. We’re not privy to all of these details, they’re all top secret. So we don’t know what is going on. And I’ve noticed, for example, in Sudan, you get a very poor country, and then suddenly a military truck is driving down the road, and it’s so sophisticated, and it’s so pristine, and the soldier is dressed really very nicely.

So a lot of money is being poured into this. And if there’s guns and bullets, why wouldn’t they use them? They’re gonna use them because they’re there. And how come they are affording all of these things in a place where they can’t afford vaccines, and they can’t afford schools and all that? But suddenly, there’s no problem, they never run out of arms, they never run out of bullets, and yet they run out of food, and they run out of all these other things. So the weapons are a big part of it.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento. Photograph of Leila Aboulela by Rania Rustom.

*

River Spirit • Bird Summons • Elsewhere, Home • The Kindness of Enemies • Lyrics Alley • Minaret • Coloured Lights • The Translator • Articles in The Guardian

Others:

“What’s behind the wave of coups in Africa,” Al Jazeera • “Chaos in Sudan: Who Is Battling for Power, and Why It Hasn’t Stopped,” by Declan Walsh and Abdi Latif Dahir • “How To Write About Africa,” Granta, by Binyavanga Wainaina, 2005 • “Binyavanga Wainaina, Kenyan Writer And LGBTQ Activist, Dies At 48,” by Colin Dwyer, NPR, May 22, 2019 • Sudan, a coup laboratory – ISS Africa • Khartoum (1966 film)

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.