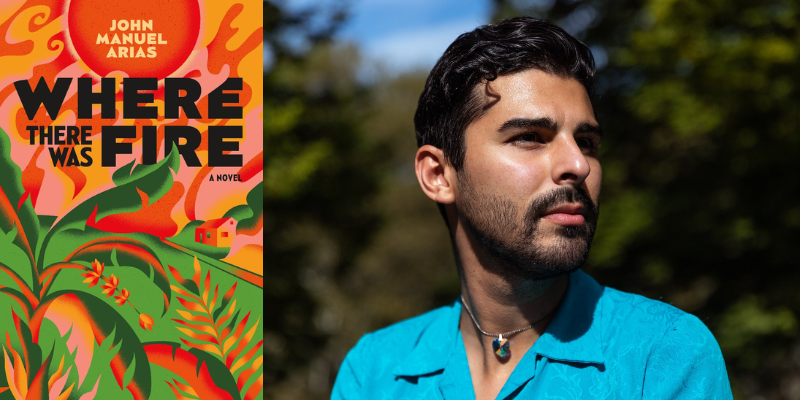

John Manuel Arias on Living With and Writing Ghosts

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

This week on The Maris Review, John Manuel Arias joins Maris Kreizman to discuss Where There Was Fire, out now from Flatiron Books.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

from the episode:

John Manuel Arias: It’s true. I did live with my grandmother and I did live with four ghosts and I knew who they are and they were quite annoying.

Maris Kreizman: What were they like? What were they doing?

JMA: Well, they’re scary. I’ve had friends visit my grandmother’s house and it’s kinda like a force field. They get to the threshold and they go, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, something’s going on here. And I’m like, no, it’s fine. You just sort of see the shadows in the – you know how old people have those convex television screens, and so you can see the entire room? – and so you’ll see the shadow sort of fly by, and then I’ve woken up and the covers on my bed have been taken off and folded on the floor and just really fun. They’re not mishaps, but they’re just minor inconveniences, which I think is what the dead do. Because they’re probably really bored. I think, what would I do if I was a ghost? I would probably inconvenience the living.

MK: I love that. In Where There Was Fire, the dead are often around. They come back and chat with the living all the time because of course if you’re bored, you wanna catch up with people.

JMA: Yeah, definitely.

MK: And so I don’t want listeners to get the wrong idea. This is not a horror novel, but it is a ghost story. Fair?

JMA: Very fair. Absolutely. I guess what sets it apart? I just taught a magical realism workshop with The Shipment Agency and it’s a craft. So it’s the way that you use ghosts, right? What are they meant to do in the story and how can they achieve that?

MK: I was gonna ask you about something that happens later in the book, and I think I’ll give it away right now. It’s not, it’s not a spoiler, I promise, but when Gabriel is in Costa Rica, he sees a woman doling out outlines from the Bible. And of course, her Bible is not the Bible. It’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

JMA: Well, that woman is me. I do walk around saying the first lines from One Hundred Years of Solitude and just talking about it. It is a cultural landmark in Latin America. It’s the one that started the boom. It put Latin America on the map on a global scale, and it just spoke to everyone who read it. I mean, my uncle has read it, I think, 10 times, in English and in Spanish. I actually really like the English translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude, the very classic one that’s been around for the last 50 years.

But One Hundred Years of Solitude is just, Garcia Marquez sat down and he showed what could be done with time, what could be done with the porous nature of what it is to be between the living and the dead. How they just come in, they hop out, and you’re just gonna hang out with them because that is just the way that it is.

So not only did Garcia Marquez write this big saga that contains elements of the magical on just about every page. So we’re going into Where There Is Fire and it’s a big story, like we see a family tree on the first page and there aren’t that many people. And yet this story keeps kind of expanding and, and the ripples of the plot kind of grow wider as we go.

MK: So I wanted to ask you a really practical question about plotting. You have a lot of characters and storylines to keep track of. Tell me how you did that.

JMA: So there are a few answers to that. And shout out to Nadxi, my editor, who very much helped. Nadxi understood, because I believe Nadxi has an MFA in poetry. And so that’s my first answer, that I am a poet, as some of you may know. And I am an associative poet, which means that my poetry doesn’t have a clear narrative. What I do is I jump from association to association in order to ground the reader in the narrative.

What I do with the book is I choose big, recognizable associations. So for example, a very hot night. It’s easy to go back and forth, right? You choose a hurricane, it’s easy to go back and forth in order to situate the reader in time because I don’t believe in linear time, both philosophically and culturally. I don’t believe that Latin America follows linear time. I think it’s a very restricting and incorrect view of the world and art and the way that fiction works, especially American fiction.

So relieving myself of the tethers of linear time allowed me to approach it in a completely different way. Because I believe that we experience time all at the same moment. So in this present moment, we are time traveling through the past with our memories and we are fast forwarding into the future with our hopes and dreams or our different lives and different selves are living those as well.

And so that’s what I put my characters through. I guess you could say that all of these things are happening concurrently. And some people might be a little bit hesitant to read that way, but sometimes it’s great to just go along with the ride.

MK: Absolutely, and I think especially for the reader, it then becomes a question of, what are we privy to when. Which chunks of time are revealed to us? Because for so much of the book, we know that there were two very tragic nights in the lives of these characters. And we know that they happened, but we don’t know the circumstances and why. And that seems like a rough thing to create a mystery around.

JMA: Yeah, I mean, it is the way that people tell stories. I learned a lot about storytelling from my grandmother, and Angie Cruz said it at her release for How Not To Drown in a Glass of Water, that when you are a person just telling a story, you have to excite the person in front of you. You have to tell it in a great way that’s going to keep them going with this narrative.

But when have you ever heard a person tell a narrative completely in chronological order? And also without having tangents? It doesn’t happen. That’s just not the way that people tell stories. So reading a novel like that would be a little bit restricting, but structuring it was very particular.

*

Recommended Reading:

Sea Change by Gina Chung • Candelaria by Melissa Lozada-Oliva

__________________________________

John Manuel Arias is a queer, Costa Rican American poet and writer. He is a Canto Mundo fellow & alumnus of the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop. He has lived in Washington D.C., Brooklyn, New York, and in San José, Costa Rica with his grandmother and four ghosts. Where There Was Fire is his debut novel.