If you are beautiful and broke, one place left for you is Asia. Usually when I ran out of money I went to Tokyo—always a face cream or a push-up bra there that could use me. This time, I went to Manila. I’d been there once before, with my roommate Sabine. In cities like these there is a demand for blue eyes and light hair and skin like milk.

Manila’s airport is a bit like Tokyo’s but noisier, more crowded, its faces a few shades darker. I towered, in both cities, over almost everyone. But while Tokyo could match New York for all its rushing, solitary people, in Manila no one seemed alone but me. At arrivals each brown face would locate the cluster of faces it belonged to, and merge into a heap of arms and laughter and chatter. Not that I had blended in much better with Sabine there. She was only half Filipina, and 5’10”—almost as tall as me.

I looked for a cab and could only get a stretch limousine—the airport’s longest person hailing its longest car. On the highway, skinny boys in wifebeaters dodged the traffic, some wearing flip-flops, others barefoot, their shins and calves dark with scabs. They carried trays of gum and cigarettes. When traffic stalled us, some boys lingered at my window, which was mirrored on the outside. They cupped their hands around their faces and squinted. Their eyes roamed, blank; they couldn’t see a thing. There were older beggars too, with body parts missing: hands, a leg, an arm.

This was the city where Sabine was born; when I’d first met her, though, I couldn’t guess where she was from. It was a question she had to answer often. “My mother’s from the Philippines, my dad is American,” she would say, in a practiced manner. “And no, he wasn’t ‘in the service.’”

Now my driver asked me the same question. “You American, miss?” he said, as he steered through the cars and bodies.

“As apple pie,” I said. It sounded more serious than I meant it.

“I can see that, miss. Where in America? Texas?”

“New York.”

“Here on vacay?” he asked, just like an American would.

I shook my head. “Work.” Then I remembered something. “Look, I’ve been here before,” I told the driver, “and I know we don’t go through Quezon City to get to this hotel.” Five years ago, the cab ride from the airport had taken three hours and cost 800 pesos—about double the time and money that we should have spent, Sabine and I later found out. We looked at a map afterwards. The driver had taken us along the edges of greater Manila and through Balete Drive, a long street in Quezon City that was supposedly haunted. While scamming us he told the story of a woman dressed all in white who roamed Balete after dark. She’d been run over by a car, he said, and now she crossed the street when least expected, causing accidents, wanting people to share her end. She favored taxi drivers or men who drove alone. One night after his shift, our cabbie thought he ran her over. He didn’t see her in the street until too late, and although he heard a thump and saw a body roll across the windshield, he found no woman and no blemish on his car when he stopped and got out. “But I have proof,” he said, rooting in his glove compartment for a length of white lace—allegedly torn from the lady’s dress and fished out of his fender hours after the accident.

After that, like a new celebrity or clothing brand, the ghost seemed to be everywhere for me. My first trip to Manila had been packed hour to hour with castings and photo shoots; I didn’t sightsee and met only those locals who I worked with. The one thing I learned about Manila was this weird and hazy ghost story, which kept on changing shape. Every stylist, every makeup artist knew a different legend of the white lady.

“They say the Japs raped her in World War II,” said one assistant on a swimsuit job, while she slaked my arms and legs with a light-diffusing cream. “Now she wants revenge against all men.”

“She stopped a Coca-Cola truck on Balete Drive,” said a photographer. “When the driver got out, she was gone. But the leaves of a banana stalk were waving nearby, even though the air was still that night.” This was allegory, he explained; Coca-Cola was America, somehow, and banana stalks the tropical Third World.

“She had big bones, and strong white teeth,” a hairstylist informed me. “The white lady was a white woman.”

I wondered now if the white lady was still popular here or if, like a clothing label or celebrity, her star had faded since my last visit. By the time I left the limousine, sweat had blossomed darkly under my blue cap sleeves. The humidity made a mist over everything; even the car windows were coated with little drops. My skin would probably break out in this kind of heat. The driver charged me 300 pesos. “Fair and square,” he said. “I’ll remember you. I’ll tell everyone there was this pretty Stateside actress in my cab, who knew her way around Manila.”

I laughed, picking up my suitcase and going into the hotel. Aside from that Balete Drive business I knew nothing about Manila. I was not an actress but a “mannequin,” as Sabine liked to refer to us. I was twenty-eight, old enough to know I would never be the Face of My Generation or the Body of My Decade, but not old enough to get it together to do anything else.

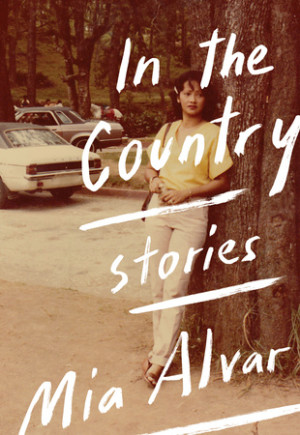

From “Legends of the White Lady” from IN THE COUNTRY. Used with permission of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Mia Alvar.