Learning How to Write Girls with Agency in Fiction

Stephanie Jimenez: Imagining Girlhood Beyond the Threat

of Sexual Violence

When I was seventeen years old, I was given a rape whistle, within three days of arriving at my undergraduate campus. I had applied to an all-women’s college far from where I grew up in New York, in part because I had read in the Princeton Review’s Best Colleges guide that it wasn’t uncommon to detect the scent of freshly baked cookies wafting down the halls of the Mediterranean-style dorms. I was used to helping my mother smash platanos for dinner, but cookies? I had never made those before. I imagined learning to bake with new friends. I was very excited.

As part of orientation, the new freshman class was ushered into the auditorium, where we received plastic whistles and witnessed a self-defense demonstration. The method, enacted from the same seminar stage where I would later learn about Darwin’s theory of evolution, was called “Slap, Grab, Twist, Pull.” It included driving an open palm into a stranger’s crotch. I was having trouble drawing a firm line between humor and horror, so when the crowd erupted into laughter, I was relieved I wasn’t alone.

I kept laughing, meeting eyes with my neighbors, knowing the presentation was just as funny, almost, as being at a college with only girls. Growing up, my mother taught me to love my gender. She made it seem like this great, sexy gift. Boys fell in love with you. You could flirt and break hearts. But when I went out past dark, she always tried to forbid it. Why? Because I wasn’t a boy. I would never be as strong as a boy.

At that point, I had lived a whole 17 years in New York City successfully averting danger, and my mother’s logic made perfect sense to me. To be a girl was to not be a boy. I knew this because as a high schooler, adult men leered at my Catholic school skirt on packed subway trains, but never once glanced at my brothers. In Queens, men stalked hallways and streets and called out to me. The thought of them overpowering me scared me.

But on my new picturesque campus, boys weren’t allowed unescorted in the dorms. Instead, we women students were invited to spend our time clipping from the rose garden and plucking from the orange trees outside our balconettes. It was inconceivable to me that this new, idyllic life in sunny California was mine, and this campus, the most beautiful place I’d ever seen, was now my home. I couldn’t reconcile that beauty with something as grotesque as rape, so when my pockets quickly became stuffed with flowers and fruit, I knew I needed more room for petals and oranges. I threw the whistle away.

*

Years after graduating college, while in the early stages of writing my first novel, a coming of age story centrally focused on girlhood, I was shocked to hear my first experience of critique. According to some readers, my main character, a 17-year-old Latina from New York City named Maria, didn’t feel like a real person.

I was shocked. The criticism seemed indirect and vague, a problem I couldn’t immediately identify and fix, no matter how hard I tried. I could alter a chunk of dialogue or identify expository writing that needed to be cut, but where exactly was my protagonist’s personhood lacking? Nobody could tell me.

As a result, I began to resent my readers, most of whom were white. As someone who had spent the majority of her life as the only Latina in predominantly white spaces, I was accustomed to over-explaining myself, especially in my younger years, especially as a college student in California who was so far from home she spent the long weekends of Thanksgiving in the campus’s dining halls. If my protagonist was not being properly understood, I rationalized, it was only a reflection of the way I myself have so often been treated like an anomaly.

Every time I demonized him, I was insisting on the sanctity of us—of our girlhood, of our friendship. Our all-women’s dorms. Whenever I said, he’s not your real friend, the subtext was obvious.

So I went on believing that there was nothing wrong with my character. Maria kept on obsessing over boys and making elaborate excuses to avoid doing her homework. She got drunk on weekends and rolled her eyes at her parents, in the same way I rolled my eyes at my ignorant readers. And there were many pages devoted explicitly to Maria’s experience of being leered at by adult men because that was the reality of being a girl—I knew because I had lived it.

I didn’t listen to people’s critique because I was attempting to write a book about girlhood, and the possibility that I was lacking the most fundamental skill for the task was intolerable to me. To acknowledge their critique felt like acknowledging that there was more to writing a concept into fiction than just feeling impassioned about it. That having once survived my very own girlhood hadn’t automatically meant I knew how to write a girl.

*

During my junior year on my all-women’s college and three years after “Slap, Grab, Twist, Pull,” I saw my classmates react to the prevalence of campus rape by organizing a SlutWalk. I didn’t participate, and when my classmates proposed the idea of hosting workshops to teach the boys from the neighboring colleges about consent, I thought it so ludicrous that I began telling my friends what I knew was the truth: Boys would never be receptive to such a thing. They aren’t really your friends.

This elicited vehement reactions. Friends proceeded to list all the guys who had been their friends in high school and camp and church—and I would respond with a variation of exactly the same point, only altered slightly according to the details I was given. “He just wants to have sex with you” would mutate into “He once wanted to have sex with you” and then “He’s now resigned to the fact that you’ve never had sex with him, but remains hopeful for the future.”

I thought my take on the matter was liberating, profound. The year was 2011, the same year that the Obama administration first acknowledged that there was a national epidemic of sexual violence on college campuses. And as I continued to have conversation after conversation, I noticed, behind the fast flick of an eyelid, that something was shifting—a perspective would recalibrate to mine and would see the dark truth that I’d been raised to see.

We are not them, I would reassure my friends, and because I was the seasoned girl from New York City, I was able to easily position myself as an expert, the one who knew all about horrible men. I told terrifying stories of men masturbating on subway platforms, of others hiding in hallways and behind doors. I knew what was lying in their dark, ugly hearts, and worse—zipped behind their denim jeans.

And in evangelizing to my friends, urging them to believe that the opposite sex was inherently untrustworthy, I had carved out a privileged position for myself. Every time I demonized him, I was insisting on the sanctity of us—of our girlhood, of our friendship. Our all-women’s dorms. Whenever I said, he’s not your real friend, the subtext was obvious. He will trick and betray you, but I know someone who wouldn’t. I know someone who understands you, and who can keep all your secrets. Someone who can help you realize yourself. Someone who will be your real friend.

*

In the summer of 2017, several years after I graduated college, I attended the Breadloaf Writers Conference and took a class taught by Tiphanie Yanique titled “Writing the Girl.” Yanique stressed the importance of giving girl characters agency, denouncing the many instances in which girls had been poorly written into literature. She stood at the center of the room with so much authority that after she wrote the word “girl” on the blackboard and asked us what we associated with the word, a minute went by in which nobody spoke.

I had wanted to write a character whose life, like most girls’, is replete with danger and sexual threat, but somehow, in the process, I was robbing Maria of all her humanity, too.

I remember how much I loved her seriousness then, the gravity with which she was treating the topic. This wasn’t easy, so you better pay attention, you better get it right, you better not do it wrong. You were writing the life of someone important. You were writing the life of a girl.

It took me until that moment to finally see what I had been robbing my protagonist of. I wanted to write a character whose life, like most girls’, is replete with danger and sexual threat, but somehow, in the process, I was robbing Maria of all her humanity, too. I was robbing her of all the things that make a person a person: a personality, hobbies, a friend.

When Maria becomes friends with one of the wealthiest girls in her grade, a girl who is radically different from her in more ways than one, she finally comes alive. The superficial and often one-sided relationships with boys are replaced by a friendship full of conflicting emotions, from admiration and awe to jealousy and anger. Whereas her interactions with the opposite sex are prescribed and dictated by society’s unwritten rules—like the one that forbids her to go out past dark—this new friendship seems limitless and fertile for growth. When Maria visits her friend’s apartment for the first time, she gingerly treads on the carpet, recognizing that what she is experiencing is fragile and rare—that there is no greater gift of intimacy as bringing someone into your home.

Through a friendship that is ultimately destroyed, Maria’s life expands in ways she could have never imagined before, and by the end of the book, the shape of her adulthood begins to emerge, as if from below a thick fog that is finally lifting.

And for me, as a writer, it was like I finally was able to see the girl beyond the sexual harm that could befall her. I no longer had to write the girl from the lens of her weakened sexuality. To be a girl, I suddenly realized, was not simply to not be as strong as a boy.

*

When I was 17 years old, I had never heard of feminism. In my all-women’s college years, my ethnicity and socioeconomic background already put me at a disadvantage in the context of my wealthy classmates. To add another bullet to my list of oppressed identities depressed me. During the “Slap, Grab, Twist, Pull” demonstration, I laughed because I did not take the threat seriously. I wanted us all to be capable of dodging the rapists each time.

I pretended there was a set of rules—our solidarity being one of them—that would always protect us.

The irony in this was that I didn’t play by my own rules, and I certainly didn’t stay locked behind the fruit-laden walls of our all-women’s dorms. I traveled to South Africa and Colombia, unafraid to venture wherever I dared. I wore stilettos and was not unaccustomed to blacking out from drinking. And despite all my talk about how evil the opposite sex was, I loved sleeping with boys.

Meanwhile, I was becoming more educated than anyone in my family. I would soon spend several years of my professional life advocating for access to abortion. I would one day become a published author.

This is the puzzle of writing characters from marginalized backgrounds—we tend to oscillate between writing them as indestructible superheroes or passionless victims.

Some people want to protect their characters, but for me, I had the opposite impulse—I wrote a character so diligently through the lens of her vulnerability that I had forgotten to write her personality.

This is the puzzle of writing characters from marginalized backgrounds—we tend to oscillate between writing them as indestructible superheroes or passionless victims. How do you accurately depict a character’s pain while also honoring their joy and humanity? How do you honestly write an autonomous woman, no less a young girl, in a world where everyone hates her?

Writers are often instructed to put their characters through hell, but for marginalized characters it might be more important to first consider they ways they’ll survive. To begin by writing their hobbies, their lives. The things that they love. Their friends.

When I visit my college’s website today and see the pictures of the sun casting blue shadows on verdant lawns, I feel awash with the sense of possibility. When I write my girl characters now, I home in on that feeling. I hold the good and the bad, the hard and the soft, and the gender binary all in my head at once. I think of my first entry point to feminism, and how it began not with weakness or power, but with the fantasy of a friendship spread on a tray of baked cookies.

_________________________________________

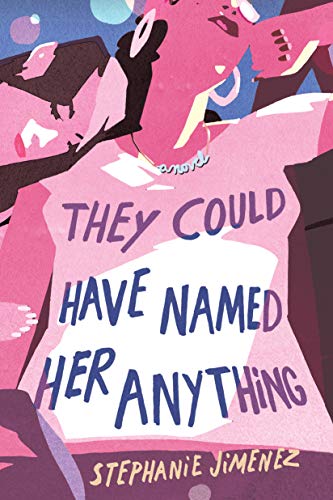

Stephanie Jimenez’s They Could Have Named Her Anything is out now from Little A.

Stephanie Jimenez

Stephanie Jimenez is a former Fulbright recipient. She is based in Queens, New York. Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in the Guardian, O! the Oprah Magazine, Joyland Magazine, The New York Times, and more. They Could Have Named Her Anything is her first novel.