Laura van den Berg on the Possibilities of Setting

"Place is ... a powerful generator of tone and atmosphere."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In Florida, the landscape is omnipresent, from the soaking heat of summer to the bluster of afternoon storms to the lizards that find their way inside, appear on counters, tabletops, walls. Perhaps this accounts for why I have to know where a story is set before I can begin. I need a sharp sense of the landscape before I can think about character or event.

The novelist Anne Enright has a quote that I return to often: “All description is an opinion about the world. Find a place to stand.” Descriptive writing of place should offer more than literal details—it should establish a sense of perspective. Place is not just a practical or logistical consideration; it can be a powerful generator of tone and atmosphere. It can help dictate what is possible in a fictional world and what is not.

Once I know where a story is located, I can start thinking about how specified the setting will be. In some cases, I prefer to leave places unnamed. My story “Friends,” for example, is set in Cambridge, Massachusetts—a place I know well—but in the story, the city remains unnamed. This ambiguity helps to give the impression of a world where leaps into the surreal are readily available.

Another story, “Slumberland,” is clearly pinned in Central Florida, but the exact area is left ambiguous. In my imagination, the story is set in my sister’s neighborhood, but I wanted to give myself some leeway with the logistics—the latitude to move a particular house from one side of town to the other, for example. Tone was a consideration, too, as I wanted the story to feel both of the familiar world and not. With other stories, the opposite is true: place needs to be named, known, clear. “Karolina” is set in Mexico City in the aftermath of the 2017 earthquake, and it felt important to render the verisimilitude of that particular moment—as I experienced it—as faithfully as I could.

This can make for an interesting writing exercise, these gradations of specificity. To explore this idea further, consider revisiting a preexisting draft and altering the story’s relationship to setting. For example, if the setting is exact, make the place partially ambiguous (i.e. the general area is specific, but the exact coordinates are withheld) or largely ambiguous (i.e. a place that could be any number of places). If your setting is already partially or largely ambiguous, consider experimenting in the opposite direction and make the setting highly particular (i.e. neighborhoods and streets are named). Notice what changes as you play with these different approaches. How does the story’s aura shift? What begins to feel possible or not? How does the representation of setting alter the fictional world?

*

Read more on developing a setting:

Brett Biebel on avoiding geographic clichés.

Rebecca Priestley on experiencing a landscape in order to write it.

Ben Weissenbach on thinking about the meaning of place.

Amanda Page on telling the story of the American Midwest.

*

3 Books with Inventive Approaches to Setting

RECOMMENDED BY LAURA VAN DEN BERG

Elias Rodriques, All the Water I’ve Seen Is Running

Katie Kitamura, A Separation

Rachel Kushner, The Flamethrowers

__________________________________

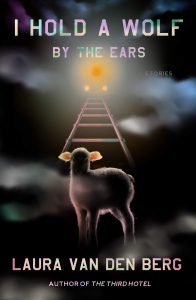

I Hold a Wolf by the Ears by Laura van den Berg is available via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Laura van den Berg

Laura van den Berg is the author of the story collections What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us, The Isle of Youth, and I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, which was named one of the ten best fiction books of 2020 by TIME, and the novels Find Me and The Third Hotel, which was a finalist for the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award and an Indie Next pick, and was named a best book of 2018 by more than a dozen publications. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Strauss Living Award and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Bard Fiction Prize, a PEN/O. Henry Award, and a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, and is a two-time finalist for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award. Born and raised in Florida, Laura splits her time between the Boston area and Central Florida, with her husband and dog.