Laura Restrepo on Blending Ancient Myth and Contemporary Reality

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Song of Ancient Lovers

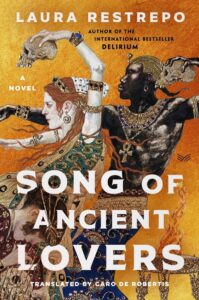

Colombian-born, internationally acclaimed author Laura Restrepo began as a writer of politically charged columns in her twenties, pivoted as a writer to telling truth through fiction, and has written novels awarded Italy’s Grinzane Cavour Prize, the Prix France Culture, and the Alfaguara Novel Prize for Delirium (also a Netflix film), among others. Her transcendent new novel, Song of Ancient Lovers, translated by Caro De Robertis, layers chapters illuminating the allure of the story of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon over the centuries with a contemporary love story set in refugee camps in Yemen.

When did you first learn about the Queen of Sheba? I asked Restrepo via email (her answers were translated by Caro De Robertis, translator of Song of Ancient Lovers). What fascinated you enough about her to devote years to writing this novel?

“The truth is, I’d never given the Queen of Sheba too much thought until she appeared to me, in flesh and blood,” she responded. “And there wasn’t just one of her, but thousands. I’m not talking about magical realism. It all began in 2009, with an invitation from Doctors Without Borders (or Médecins Sans Frontières, MSF), to travel with them and report on some of their camps in areas mired in severe humanitarian crises and wars forgotten by the media. The goal? To raise visibility by publishing eyewitness articles by established authors that would be literary as well as informative. There were twelve in our cohort, and each of us would be dispatched to a different country. MSF didn’t tell us our destinations beforehand; they were decided at the last minute, due to security considerations. Mario Vargas Llosa was sent to the Congo. Sergio Ramírez, to Haiti. And so on.”

A day before her departure, she was told: you’re going to Yemen. “I accepted immediately, even though I knew little about the country, just three things: one, that it was in the middle of a war, under constant bombardment by an alliance between Saudi Arabia, Great Britain, and the United States. Two, that it was basically a desert, but that its capital, Sanaa, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, was extraordinarily beautiful. And three, that in the early twentieth century, André Malraux had flown over it in a small plane in search of the Kingdom of Sheba’s lost ruins.

“Though he never found them, Malraux had left a record of his adventures in a small, wondrous book I’d read a few years before. I asked to travel with my son Pedro, and I assure you that it would never have occurred to me to think of the Queen of Sheba on landing in Sanaa, at an airport brimming with refugees and loud with nearby bombings, where the labyrinthine customs process kept us detained for 48 hours.

“The miracle happened a few days later, as we were driving through the desert in MSF’s Jeeps and ambulances and saw them approach, like a cloud or mirage: hundreds of women with their children, displaced by war, crossing the vast sands in search of an impossible place, where life could be possible. They were barefoot, in tattered clothes, hungry, thirsty, skin burned by sun and salt. I approached them as a journalist, and, one after the other, when (through an interpreter) I asked their name, origins, and where they were going, they responded, with great dignity and pride, I’m a descendant of the Queen of Sheba. Their tone held no plea, nor wish for pity. They were saying to me, you come here in a car and wearing good clothes, in your own country you must have food and a roof, while we have nothing and roam unhoused, but…blue blood runs through our veins, and ours was the most powerful civilization on earth when yours didn’t even exist.

“In that moment, legend and reality fused before my eyes. Myth was made flesh. Malraux hadn’t found the Kingdom of Sheba’s ruins, but I just had. These women were the resurrected Queen of Sheba. In that moment, I knew I wouldn’t only write the article MSF had commissioned, but also a novel, with two related layers: the sumptuous ancestral myth, and the current brutality faced by these migrant women, who were proud and sovereign despite the horror of war. They themselves had given me the key to their dual nature.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did you develop the characters of Bos Mutas, a South American so enthralled with the Queen of Sheba he travels to Yemen to research his dissertation on her, only to be detained at the Sanaa Airport, “unable to enter or leave, stuck in the middle of an anonymous crowd that throngs and struggles not to die of heat, hunger, war, disease,” and Zahra Bayda, the Somali midwife with years of experience with MSF, who helps him find his way out of the airport into volunteer work at the refugee camp?

I thought it would be more interesting for the narrator to be a man, rather than a woman like me. A man, even more surprised and driven to seek explanations, both for the myth and for realities.

Laura Restrepo: I needed a narrator for my story. In the article, which was eventually published (as were those of the other authors) in the newspaper El País, the narrative voice is my own. But for the novel, I created a fictional character, a kind of alter ego who discovers the wonders and realities I witnessed on that trip to Yemen, on later trips to Ethiopia and Somalia, and in the years of book research that followed. Like me, Bos Mutas is Latin American—we have that in common, as well as both being complete foreigners in the lands in question.

But I thought it would be more interesting for the narrator to be a man, rather than a woman like me. A man, even more surprised and driven to seek explanations, both for the myth and for realities. In my novels, I usually explore themes at a slant, that is, not head-on, but at an angle, through improbable protagonists, so as not to fall into more common, expected modes. I was intrigued by the uncertainty and, in some ways, clumsiness the story would get from this ex-seminarian, this young dreamer, Bos Mutas. Also, I was drawn to the possibility that he might not only be curious about the Queen of Sheba, but also directly and passionately in love with her (or one of her incarnations). That would allow a raw, hard story to become a seductive one, a story of love.

As for Zahra Bayda, unlike Bos Mutas, she’s a character lifted almost entirely from real life. Her real name was Habiba—I never learned her last name—and she was a doctor, working as a midwife for MSF. Habiba/Zahra Bayda was my interpreter and guide. On the journey, we became good friends, and during our spare time she told me her life story. Later, in writing the novel, I brought that story to the fictional character of Zahra Bayda. Because of the security issues on that trip, Habiba and I never said goodbye. We couldn’t even exchange email addresses. To this day, I haven’t been able to find or reach her. I don’t know whether or not she’s still alive; MSF has no news of her whereabouts.

JC: How did you develop the historic/mythic narrative about the Queen of Sheba, aka Goat Foot; her rivalrous mother, the Maiden; her journey to becoming the Black Lion of the Desert, her choices over the years, and the complicated relationship with King Solomon?

LR: I wove in many stories about the Queen of Sheba that I heard in Yemen, Ethiopia, and the Somali camps. She is revered in those regions, and oral tradition keeps her myths alive. I also drew on a great deal of later reading. Some stories, I made up; in reality, quite a bit is the product of my imagination, because the truth is, the only original references to her that have survived are a short paragraph of the Bible, and an equally short one in the Koran. That’s it; the rest is recreation.

There’s much more historical material about King Solomon. I drew on that, starting with the Old Testament.

JC: Goat Foot develops a powerful trade in incomparable perfumes, which include “an epically layered and poetic perfume that speaks of desperate love affairs and ancient bloody battles,” made of four secret ingredients–olibanum, an extract from the musk gland of a red stag, black rose, and “tiny dead particles of herself,” drawn from a piece of one of her fingernails, “a tip of her hair, a drop of her bodily fluids or flakes from her skin.” Are these formulas based on history/myth? Are they still used in perfumes today?

LR: Olibanum still forms the base of perfumes, using ancestral methods—especially in Oman, Yemen’s neighbor, where it has been a major product from ancient times to this day. Expensive, exclusive perfumes are manufactured there, such as Oman Luxury and, above all, Amouage. Though I learned there’s a perfume made in Switzerland that approaches these: L’Air du dèsert Marocain, by Tauer. So my answer to this question is, Yes. But who knows whether traces of hair or fingernail are included in these products; perfumers tend to lie about their formulas, to keep them secret.

JC: What sort of research was involved to detail connections of thinkers and artists like Thomas Aquinas, Gerard de Nerval, Andre Malraux, Arthur Rimbaud, Frida Kahlo, and Patti Smith to the Queen of Sheba? Did you visit Maison Rimbaud in Aden?

LR: Throughout the centuries, several great thinkers, writers, and poets have devoted whole pages to their own versions—historical or imagined—of this extraordinary myth, which renews itself each time. I found it while rereading authors as varied as the medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas, for whom the Queen of Sheba is the “light of the Orient,” or wisdom through love. Or Gérard de Nerval, the great nineteenth-century poet, who brought her to life with such agony and fervor that, after his suicide in a dark alley in Paris, his friend Thèophile Gautier declared that he’d hung himself with the silver-and-wool rope the Queen of Sheba wore around her waist. Since these and other historical figures had contributed to the myths, I decided to make them characters in my novel, giving life to the strange, fascinating dynamics they had with the Queen. I mean, I’d already taken my fusion of truth, myth, and fiction so far, why not keep going?

As for Patti Smith, I found that Rolling Stone had called her “the punk Queen of Sheba.” This seems right to me. If anyone could be the reincarnation of that ancient rebel Queen, it’s Patti Smith. One of the most fascinating legends says that the lady of Sheba was disabled (“goat foot”) because she descended from a long tradition of royal women with deformed feet, which was later continued by a lineage of French queens known as “large-footed.” I enjoyed exploring the possibility that Patti Smith, as well as Frida Kahlo, having experienced such physical disabilities, were modern inheritors of this tradition.

And yes, of course, I visited Rimbaud’s former home in Aden, in the south of Yemen, a port on the gulf of the same name, where MSF’s work is intense and the human realities harsh, as migrant Africans arrive there half-dead after crossing the sea in dinghies, trying to reach the Arabian Peninsula. Some drown on the journey. But Aden also holds the hotel where Rimbaud once lived, while working as an arms dealer, as well as slave trader, according to some biographies. It’s an enormous wooden building, quite run-down, its dull green paint peeling.

Today, it houses many families. So, to reach Rimbaud’s former home, you have to go up several flights and through halls full of hanging laundry, hotplates steaming with food, and playing children. Rimbaud’s quarters consist of a small room, simple and dark. Since there’s no guide, you find it almost by chance. The only signs you’ve found it are a few faded photographs stuck to the wall, and a small glass case for his personal items: a shirt, and a camera, which is no longer there, but a label says it used to be. It’s not much, and yet it’s a lot, and it’s moving.

JC: How did you gather information for the stories of the refugee camps? Did you spend time there?

LR: Yes, on several occasions, during week-long stays in various regions. The theme of migration runs through other novels of mine, as well. I’m familiar with it first-hand because I belong to a country, Colombia, with an ongoing, constant war that’s displaced millions of people, both internally, and beyond our borders. With MSF, I often visited camps and tent hospitals—for Yemeni, Somali, and Ethiopian people, but also for Palestinians, for Syrian refugees in Greece, in Mexico, in several parts of India, and in my own country.

JC: What ancestral ties do the women in the MSF camps in Yemen where Zahra Bayda and Bos Mutas work have to the Queen of Sheba?

The Queen not only forms part of their history and mythology, but also of their present; they feel that it’s her same blood running through their veins.

LR: The camps offer refuge to women who migrate in great waves from Yemen, Somalia, and Ethiopia, places where the Kingdom of Sheba once was, or so it’s believed. As such, the Queen not only forms part of their history and mythology, but also of their present; they feel that it’s her same blood running through their veins. They revere her, tell many versions of her legends, and speak of themselves as her descendants. Her presence is alive in these women.

It’s not the only living myth in Yemen, where past, present, and future blend into one, and Biblical times seem to extend into ours. It’s something that, when you’re there, is a constant surprise. For example, I was taken to see the place, near a camp, where the remains of Noah’s Arc are buried. Another example: Ethiopians venerate the Arc of the Covenant, containing the tablets of the Ten Commandments, which, according to them, is a sacred relic to be found in their lands. I’m telling you, in that area, yesterday and today are profoundly connected.

JC: A few questions about the translation. How do you and Caro De Robertis work together in crafting the translation of Song of Ancient Lovers into English? Does it help that you have worked together before, on The Divine Boys?

LR: It’s been my immense good fortune to be translated twice by Caro De Robertis, who in addition to being a translator, is an extraordinary writer, and who deeply knows the subtleties of language—in both English and Spanish. Their translations of my books are so natural to me, that, upon reading them, I at times forget that they were originally written in Spanish. My gratitude goes to Caro, as well as to Gabriella Page-Fort, my editor at Harper Collins, thanks to whom my books are beautifully edited for the English-speaking public. And thank you, also, to Jane Ciabattari for these questions, which I appreciated for the way they point toward the soul of the book, and which I’ve enjoyed answering.

JC: Thank you for taking the time while traveling, and Caro De Robertis for translating. What are you working on now/next?

LR: Like the perfumers, I too guard the secret of what I’m concocting. The Cuban writer Lezama Lima says it beautifully: “I tell my secrets, but I don’t reveal my mysteries.”

__________________________________

Song of Ancient Lovers by Laura Restrepo, translated by Caro de Robertis, is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.