Saved, yes. David Rizzo knew his son’s resurrection had saved his gun shop. The arrival of this fact abrupt, vivid—brought him to silent tears behind the wheel of his unreliable Eldorado. He drove through txhe depthless desert sky, wiping his face, the world a smear of bare earth and sunlight. Rizzo’s Firearms, rescued. His son, not dead. It settled between his stomach and his throat, this stark revelation.

As Rizzo drove to the hospital on that heat-sick afternoon to pick up his son—drove fast across the tall loop of the freeway, over the lifeless suburbs: Sonora Gateway, Arroyo Foothills, Moon Valley Manors; above the carnival spreads of outdoor shopping centers: Desert Ridge, Scottsdale Quarter, Metrocenter; past the pockets of turf fields, car dealerships, adobe churches, drive-through liquor stores, uncharmed apartments; as he drove on beside the midday glitter of the casino, Talking Stick, across boundless land streaked with posing saguaros, then the barbed purple columns of the east valley mountains, Superstition, toward the minor glass of downtown—yes, as Rizzo drove through his home of Phoenix, Arizona, he began to unbend all the angles of his elaborate salvation.

All his life he had waited for a sign from above. Here it was, his estranged son, back for a reason. It had been more than a year since he had last seen the kid. And of all days this one: when Rizzo was supposed to sign the shop away, the call came. Overdosed three days ago, he said. Flatlined. Nicholas, on the phone with that familiar mumble, meek and sorry. It was obvious: if his son could return from the dead, so could Rizzo’s business. Now, in the clay-colored valley of the desert, all was glory, all was light, all burned with the eternal grace of the divine.

The Eldorado’s engine was smoking. Rizzo, distressed, parked in what seemed like the only open spot at Banner Health. His shit engine. Outside the car he paced around, afraid the whole thing might catch fire. Seared the shit out of his fingers when he tried to lift the hood. He twisted his pinkie ring, patted the gray curls at the back of his head, hoping the coils of smoke would suddenly quit. They did not.

After walking a mile to the Circle K for some coolant—a lonelier journey than Rizzo anticipated: he leaned through the dust knocked into the air, the one man on the roadside, and the sound of every truck bed rattling past made him feel as if he was somehow left behind—Rizzo got back to the hospital just in time to watch his Eldorado be loaded onto a tow truck. How could he have missed the sign that said those spots were reserved for medical vehicles? Rizzo, dumbstruck, sweated through his silk shirt, still hugging the container of coolant, unsure of how to spare his Cadillac the sad ordeal of the tow yard.

“You see that last night? Six dead. Fourteen injured. Sorority girls, deputies, cyclists,” the tow truck guy said, tearing several identical pieces of paper from a clipboard. He was a man of frail build and dense beard. “Makes you wonder. Some maniac in a car, mind gone, shooting everyone. You never know. Right here right now. Could be us. Except this kid hated women or something and wanted to kill them all. But hey, you never know. We could be women. It could’ve been us. Random, everything, right?”

The tow truck guy socially pondering a recent massacre meant the vehicle was safe—or so Rizzo thought, but then a button was pressed and the car rose with a groan to the flatbed.

Of course this was not a big deal. In the grand scheme. Calmly Rizzo, inside the hospital, introduced himself to the first-floor receptionist, who sent him to the second-floor receptionist, who held up a finger while she called the first-floor receptionist before unloading Rizzo on Maria, a lisping medical assistant who, phone pinned between shoulder and ear, steered a stretcher through the packed hall. “Unforgivable. Totally unforgivable,” Maria said to her phone. Rizzo jogged beside her, explaining. His son? Yes, his son, you know: Nick Rizzo—the tall kid with the crazy hair who might be decent-looking if he put some weight on—brought in because of an overdose? But Maria did not know. So Rizzo repeated all he knew, how he had been trying to reach his son on the number the kid had called from but got only a busy signal. In response a laconic Maria said to take the elevator to the third floor and walk to the east wing, two lefts, a quick right, and Rizzo said he planned to do just that, but he first wanted to talk to the doctor.

The old guy spread on the stretcher pointed a finger at Rizzo. “Do me a favor, please. Hey. Okay? A favor.” He was a wrinkled man with striking eyebrows. “Tell Charlie Miniscus I hope he rots in hell.”

Everything stayed in motion: Maria with her stretcher, but also a flurry of creaking wheelchairs, wobbling gowns, a traffic of the diseased and the damned—and there went Rizzo, weaving to keep up, embarrassed and breathless.

“The doctors are in meetings,” Maria said, walking faster now. All of them? “One second,” Maria said, to her phone, while looking at Rizzo. She said she understood now, and then repeated her earlier directions: third floor, two lefts, a quick right.

The guy on the stretcher again: “Rot in hell, Miniscus!”

Rizzo smiled at everyone in the elevator so that they all understood how completely fine he was. Oh, he was so fine. A sallow man in the corner of the compartment wept, Rizzo noticed, while incanting the word kidney.

Maria’s directions brought Rizzo to a florid man in a suit who, with his legs crossed in a wheelchair parked near a bathroom, stood to introduce himself. “Chad Garlin. Hey there, how you doing?” Chad—who was just fantastic, thanks for asking—happened to be a medical supplies salesman from AventCore specializing in heavy-duty gauze. “Best stuff for your gunshot wounds, your buzz-saw wounds, any impaling situations.” And he was on break, technically, Chad choosing this wheelchair here because he spent much of his day walking up and down the stairs for his meetings with doctors. “Good way to get my steps in,” Chad continued. Up, down. Up, down. Half his day, lost in the dumb metal heat of the stairwell. How many steps had Rizzo taken today, Chad wanted to know. How many? Chad mimicked a marching motion. It amazed him how doctors could be so oblivious when it came to their own health, he said, slapping Rizzo’s shoulder. “Oh, is that right, not a doctor?” Chad, dimming, lowered himself back into the wheelchair, then directed Rizzo with a wave toward a far window.

Rizzo found the area disastrously hot, the hallway a blur, and the only person around was the janitor, a confident man with a limp, mopping, who explained they had moved all the patients in the third-floor east wing to the first-floor west wing because of the busted AC. “Or at least that’s the story they’re telling,” the janitor whispered. After listening to the janitor’s theory—basic experiments: risky organ removals, unproven pharmaceuticals—Rizzo was back in the first-floor west wing, near where he had entered, and soon he figured out from a cafeteria worker with an eyebrow piercing that his son was no longer in the hospital; that is, his son had been sent across the street to the health system’s psychiatric center, the place they used for the detox spillover.

Not that any of this frustrated Rizzo. Oh no, not one bit. It all almost made sense.

Rizzo halted and sprinted in accordance with the traffic on his way to retrieve his son. After a day in a coma, after three days of detox, Nick looked even worse than Rizzo expected: pale, sunken, forlorn. He had a lazy beard and the curls in his hair were greased to the right side of his head. Nicholas Rizzo, his stupid fragile son. He stood there in the lobby waiting, glum and unkempt, in jeans and a flannel. Behind the front desk a man said, “And in my opinion he got what he deserved,” into his headphones. Rizzo gave his son a firm nod that he hoped communicated what a shit time this would be to talk.

Outside they waited for an Uber in silence. It was at this point that Rizzo realized he was still holding the container of coolant. The car that came was a minivan, and the driver apologized about all the stuff they needed to climb over: dented boxes of TiVos, iPods, DVDs, smart alarm clocks, noisy baby toys. The driver was helping a friend unload some stuff—speaking of which, the driver said, a thumb over his shoulder, if they saw anything they liked? Let him know. He could maybe possibly perhaps make a deal. So just let him know, okay?

They sat crammed in the last row. “My phone,” Nick whispered, all the sudden. A frantic pat down followed. “Shit.” Leaning back, dejected. Then, hands behind his head: “Hey, Dad? Thanks for coming. I’m sorry about all of this. But things are different this time, I don’t need rehab. The hospital was enough.”

In a rare occurrence, Rizzo agreed. This rehab crap? Not worth it. Same with NA. For some it helped, but for others, like you, my son, all it does is acquaint idiots with more accomplished idiots. So instead of rehab Nick would work—as in, work for his father’s business.

“Oh.” Nick, scratching his head. “Wait. You’re still doing the gun thing?”

It would be easy to sleep tonight, Rizzo knew, because there was absolutely nothing to worry about. Rizzo was okay. He was at the kitchen table with a cigarette. This was a good table, a scarce heirloom, the surface tiles painted by his own grandmother, the place where many a Rizzo had graced a meal with a pile of complaints. He looked around the house. The desert landscape paintings of uncertain origin. The little crucifix hung beside a wrought-iron star. Envelopes stacked on the counter beneath a cordless landline. Rizzo now began to feel these objects no longer belonged to him but rather to the house itself, this collapsed version of a home with its low ceiling and an open kitchen and a single hallway, a structure identical to those owned by neighbors he had never spoken to nor seen but whom he knew existed by the infrequent grating lift from their garage doors. He was the rare year-round resident in a community of second homes. Rizzo ashed his cigarette in a plain mug his wife for some reason had liked, staring through the dust-streaked glass of the slider door at the yard of decorative rock.

It would make sense to worry if he had no plan. His thirty-year-old son, back again, marooned in the house, and no plan? His business, his stupendous debt, and no plan? But there was no need to worry because he knew he would come up with something, a way to save his gun shop, his son, himself. There was no need to worry because, the last time Rizzo checked, this was still America, and in America there would always be hope.

*

So then why was Rizzo crying?

Why?

Mere hours after he had been so certain, and yet here he was outside, as far away as he could be from his son—who sat like an idiot at the kitchen island, hauling cereal to his face—in a corner of his backyard, poorly obscured by the drooping mesquite, crying?

Crying, in what was officially the palm tree twilight?

Beneath the mountains streaked in a brittle green? In a backyard so new, so ready for use, with fake flagstone, a propane grill, and heat-cracked wicker chairs? Why?

Who cries in paradise?

__________________________________

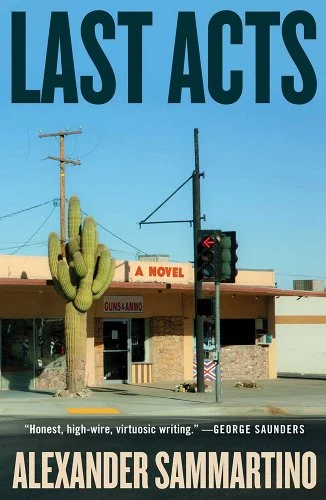

Excerpted from Last Acts by Alexander Sammartino. Copyright © 2024 by Alexander Sammartino. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, LLC.