Kyoko Mori on Writing Through Deep Trauma

How a Celebrated Memoirist Works Through Childhood Wounds

Within two minutes of our first meeting, on a morning in September 2015, Kyoko Mori, the acclaimed author of fiction and nonfiction, is balancing her Burmese cat, Jackson (short for the singer Jackson Browne, “because he’s brown,” she explains), on her head and showing me how she can wear him like a hat. I immediately recognize that, despite her impressive backstory, this petite woman, dressed comfortably in jeans and a navy-and-red-striped t-shirt with a polka dot pocket, her long, dark hair hanging loosely past her shoulders, does not take herself too seriously.

Mori has just given me a quick tour of her stunning third-floor apartment in a stately red-brick building nestled amid 19th-century homes in Washington, DC’s Cleveland Park neighborhood. Characterized by high ceilings, architectural nooks and shelves, and a fabulous floor-to-ceiling bookcase with a rolling ladder filling the entire back wall of her living room, the cozy apartment feels ideal for a writer. I don’t have to stretch too hard as I scan the space to figure out that Mori is a passionate admirer of cats, birds, and flowers. Wooden boxes with colorful blossoms adorn the exterior of her tall back windows, a hummingbird feeder hanging over the top. An eclectic mix of artwork scatters her walls: watercolors, ink sketches, and tapestries, featuring the aforementioned cats and birds and flowers.

Unlike his extroverted brother, Mori’s second cat, Miles, a sleek blue-point Siamese (named for blues musician Miles Davis, “because he’s ‘kind of blue’”), runs to hide in a closet at the first sight of me. In a while he’ll warm up and dig through my bag until he finds a scrap of paper to pull out and chew. Later, both cats will charm me with their repertoire of tricks—a routine of leaping over plastic sticks, jumping through hoops, and climbing up shelves at Mori’s commands. Her deep affection for and devotion to these cats is obvious. She admits midway through our conversation, “My whole adult life has been a process of understanding that I really don’t like to travel. I like to stay in one place, you know?” A big reason for that, she tells me, is that she hates to leave her cats.

Paradoxically, though, the theme of displacement has been at the core of Mori’s writing, particularly her nonfiction. Her two memoirs, The Dream of Water and Yarn, and her collection of essays, Polite Lies, all share the thread of her life spent straddling two very different cultures and trying to determine where she belongs.

Mori was born in Kobe, Japan, in 1957. When she was 20, she moved on her own to the United States to study writing, attending Rockford College in Illinois for her undergraduate degree and receiving a master’s and PhD in creative writing from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She spent much of her adult life in the Midwest, just outside of Green Bay, writing and teaching at St. Norbert College, until she received a prestigious five-year appointment as Briggs-Copeland Lecturer at Harvard University and moved to Boston. She later moved to Washington, DC, and is now a full professor in George Mason University’s MFA program and also teaches in Lesley University’s low-residency MFA program.

The story that propelled Mori 6,000 miles from her Japanese homeland is rooted in trauma. When she was 12 years old, Mori’s beloved mother put a plastic bag over her head, unhooked the gas line, held it to her mouth, and killed herself. Two months later, her father moved his mistress into their home, and for the next eight years, Mori was cut off from her mother’s family and endured physical and emotional abuse from her father and stepmother. Her move to the United States was, in all senses of the word, an escape.

In 1990, during a sabbatical, Mori took her first trip back to Japan since her departure 13 years earlier. She toured the country, including her hometown, and spent time with relatives, many of those on her mother’s side whom her father had forbidden her to see so many years before—aunts, uncles, cousins, and her 94-year-old grandmother. “I came away from those visits thinking I was going to write a novel,” she tells me. She’d just finished her first novel, Shizuko’s Daughter, a coming-of-age story set in Japan that, in many ways, parallels her own coming-of-age story, and had contracted with an agent. “What I was going to write now was going to be almost like a prequel to Shizuko’s Daughter, about the older people in the family.”

Mori’s mother’s family was deeply affected by the events at the end of World War II. They lost their land, their livelihood, their entire city destroyed by firebombs. Mori was born only 12 years after the war ended, and the specter of its impact was embedded in the childhood stories she remembers from her mother and grandmother. “So I wanted to write about that, you know?” she says, tucking a foot under her other leg as she relaxes into her chair across from where I sit on the couch.

The more she talks, the more I notice the distinctions in Mori’s speech. Her words still carry traces of her Japanese accent, but her inflection and dialect are distinctly Midwestern. She peppers her talk with “you know?” as a habitual punctuation to her points. “But, because I hadn’t experienced it,” she continues,

“I couldn’t even imagine, you know? It would be easier to write a historical novel about, like, five centuries ago than a historical novel about an event you kind of missed just by a few years. So I couldn’t do it. And then I was going to write nonfiction about it, but for the same reason, I couldn’t. I realized: who am I to write their story?”

Mori had to reevaluate her purpose: if not these stories she’d had in mind, then what? “I kind of wasted my sabbatical writing things that were never quite right, but I think I had to write all of that to get to the right place.”

It took her some time to recognize that the “right place,” the real story, the big story—the story about going back to Japan and realizing that in no way could it ever be her home—had been there from the moment she boarded the airplane. “I really think that so much of writing a book, especially the first part, is like avoidance,” she explains. “You avoid the real story because at once you think it’s too painful and too boring. I mean, some days, I think, God, I don’t want to go there because it’s too painful. But most of the time, I think, God, it’s too boring.” She tilts her head back and laughs. “That is like a deadly combination when you think of the most painful thing that happened in your life as being kind of boring, you know? Who wants to hear that?”

The question of whether people would be interested in reading this story was coupled with the question of how Mori was going to write it. Though she’d written a few essays by this time, she didn’t feel completely at ease in the nonfiction genre. “I hadn’t written a lot of nonfiction and definitely not a book-length narrative.”

“So how did you get started on it?”

“I was always a fiction writer who heavily based stuff on things that I experienced, and I was always in the habit of writing in my journal. So, when I was in Japan, I had a journal that I wrote in, like a notebook, and then I also had kind of like an appointment calendar, where I wrote down where I went and just a few comments. So, between those two, I had a really good record of what I did every day.”

Operating from a fiction mindset, though, Mori needed to figure out the plot that would drive the story from beginning to end. “I always think plot has to rise out of character, and that is exactly the same whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. It’s really about that person realizing something or working toward something or coming to terms with something. There has to be conflict, you know?”

Mori’s journey to Japan was rife with conflict: encounters with friends and relatives she hadn’t seen for years, revelations about both her mother and her father, palpable reminders of her life before and after her mother died, a painful reunion with her father and stepmother. She still struggled, though, to find a way to tell it that would be authentic. She was still avoiding. It was only when she decided that she really had to tell two stories to write this memoir—the story about her journey to Japan in 1990 and the story of her past—that the writing opened up for her. “I finally kind of saw the whole structure. Now I was writing with a purpose. I was going in the right direction. Whatever I was writing, even though there would be a lot that would change, I wasn’t just taking a stab in the dark.”

“So what was it like for you as you began writing about this journey and revisiting the painful history that it unearthed?”

“By then, I was so relieved to not have to be writing a novel I couldn’t finish or writing about people that I couldn’t keep interviewing because they lived in Japan. I was so relieved that I had everything I needed for this because it was in my journal, it was in my memory, and I also had artifacts—letters written by different members of my family in the past. I had those in a box along with photographs. I was just so relieved that I didn’t have to go anywhere else to collect any more material.”

For Mori, the writing became a kind of reprieve at a time in her life when she felt restless and self-conscious. “My whole life in Green Bay, I realize in retrospect, was [that] I never really felt like myself. I was such a minority in every way: as an educated woman, a Japanese American, a writer in my department at the college where I was the only writer. I just felt like I was on TV somehow as a kind of strange, peculiar phenomenon.”

She had a writing studio in her basement. “When I went down there to write,” she explains, “and it was just me and the writing and Dorian (her cat who lived for close to 18 years) who just came and sat next to me, I felt great. Finally I got to be myself. So, I don’t think I cared so much about the fact that the material was hard. Just living was hard.”

That Mori had experience and saw herself as a writer also helped her through the process. “I did worry that nobody might read it, but I didn’t really worry that I shouldn’t be writing it, because if it didn’t work out, nobody was going to read it, so how would it hurt anyone?”

I reflect on the fact that most of the people involved in Mori’s first memoir live in Japan and speak Japanese, and there was a high probability that they would not read the story Mori was writing. “Was there a certain level of safety because of that?” I ask her.

“Completely,” she replies. “They wouldn’t read it, and I knew I could elect not to have it be translated into Japanese.” She adds, “It never was.” She leans over to pick Jackson up from where he’s insistently brushing back and forth against her leg. She smushes his face against hers and then settles him on her lap. “The thing is,” she says, running her hand absently across Jackson’s back, “these were all the people who had all the power when I was a child. And I had no power as a child. So no matter what I said about them as an adult, it couldn’t even begin to tip the balance. I felt like they kind of owed me, you know? I didn’t talk 20 years ago. It was now my turn to talk.” I think of so many of the other writers I’ve spoken with who’ve talked about this same determination to find their voices, despite the rules that might silence them. “Do you think we all have to launch some sort of rebellion against the family rules when we write these stories?” I wonder aloud.

“When you write about somebody, you are taking control. When you, as the writer, sign on for this, you kind of just have to accept this is how it’s going to be.” Mori laughs. “I just think that anyone who marries or goes out with a writer, they should understand that they are signing up for this. I would love to say to people when I associate with them, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll never write anything about you,’ but it would just not be true. So you might as well forget that.”

Mori gestures toward my copy of Yarn, her most recent memoir, lying on the coffee table. This narrative is a literal weaving together of her own history with the history of the creative art of knitting, set against the backdrop of the quiet dissolution of her marriage and her eventual departure from Wisconsin. “Writing about my parents was totally different than writing about my ex-husband. Entering into that [the story of their marriage] was so hard. How can I write about somebody I spent so much time with? And the upshot is that we’re not together, and how can I do it in a way that’s respectful? I was so much more careful in Yarn not to say anything that I hadn’t already said to Chuck, not to portray him in a way that would be surprising to him or anyone else. I would never reveal anything about him that everybody didn’t already know. We had a good relationship. We still do, even though we haven’t seen each other in a long time. We’ve always been in touch in some way.” She pauses, her face serious, obviously thinking through her next words. “I think this is the idea that this is a person I chose to associate with, and I can’t walk away thinking that I didn’t respect him enough to treat him with dignity.”

Mori reiterates that the same contract is not true with everyone in her life. “With my parents, I didn’t ask to be their child. So writing about them was totally different. My mother made her choice to die, and she died. It wasn’t necessarily Chuck’s choice for me to leave.”

In both The Dream of Water and Yarn, Mori lays bare some heartrending moments from her childhood: Coming home to find her mother dead and then being left alone with her mother’s body while her father goes to meet the doctor. Suffering silently through her own grief, while her father upends her whole world with the introduction into their home of his hateful and manipulative mistress. Meticulously following a nightly routine of propping chairs up between the door of her bedroom and her bed and scattering books and tennis balls on the floor to act as deterrents for her father and give her time for escape if he made good on his ongoing threats to stab her with a meat knife. Mori also guides us through the painful realities of coming to terms with many of these experiences and trying to understand their influence on the person she is today. I ask her how difficult it was for her to give words to these experiences.

“I think they were not quite as difficult only because I thought about them all the time anyway. I think when a reader reads something like that, they’re reading it for the first time. But when you are writing it, you’ve already thought about it so many times. Which is why sometimes it seems like it’s even almost boring. It’s not shocking to you because you already know it so well.”

Mori is pragmatic about the emotions the writing did stir up. “In writing about it, I realized that I was still sort of mad about it in ways I never thought I was.” She chuckles. “But I also never expected to feel better about any of this stuff after writing it because if that were the case, writers would be like the best adjusted people in the world.”

For Mori, the “feeling better” part happened with the satisfaction of completing the book itself. “I didn’t feel better about what happened, but I felt better about the book. It was like a substitute.”

Finding the right shape and structure for both of her memoirs was a lengthy and solitary struggle. Mori’s not someone who shares her writing in process. And, she admits, she’s not someone who confides in people when something in her life is in process. “I think it is a personality thing,” she explains. “And a Midwestern thing,” she adds. “When I make major decisions, I don’t usually talk about it until I’m pretty sure I’m going through with it. Then I might tell a couple of people. I like to figure it out on my own. I’ll let you know when I figure it out.” The page becomes Mori’s confidante. “The impetus for writing really is so that then you can talk about your feelings.”

When the manuscript is finished and sent, Mori explains, “then it’s done. Now I can talk about what it was, and to finish it and find a publisher. That was a huge big thing. I felt great. I was finally done. Now I could go do something else.” Even though she’s gone on to do those “something elses,” her other stories, in various ways, still contain morsels of her backstory. I ask her about that ongoing confluence. “There are just sort of certain touchstones in your life that you always have to come back to—you know, the place from which all of your writing originates. My mother’s death was definitely one of those for me. The decision for her to die. And, also, the decision for me, in some ways, to let it happen. I mean, I knew she was going to do it. I knew I couldn’t stop her. And I wanted her to know that I was going to be okay without her. That is such a touchstone for me, that moment of letting her go.”

Jackson jumps off Mori’s lap to investigate what Miles is doing with the paper he’s nabbed from my bag. “I think this is where nonfiction is like fiction, in that there are things you realize later and you layer it back in. You know, the stuff you did not articulate to yourself then.” She explains that in these realizations, the world becomes a bigger place with broader possibilities.

“Did this broadening of thinking change your feelings about your story when it was finally in print?”

With the same pragmatism as earlier, Mori answers, “I think I became more solidified in everything I said because it was out there. It wasn’t like I saw things more clearly, but everything I said, I couldn’t take back. Here was the official version. An official version for me, too.”

I tell Mori my personal fears that putting my story in print will box me into being that person on the page. “Do you ever worry that people will assume these ‘official versions’ are the only versions of who you are?”

“I don’t really worry about it. Even if it’s a recent book, I think anybody who reads should understand that the most fundamental thing about writing is that the persona in the book is not all of who you are. Even right now. It’s like a part of who you are, strengthened many times.”

She tells me about how her first novel, Shizuko’s Daughter, a New York Times notable book, was first translated into German and then Korean, even before it was translated into Japanese. “That, for me, is a metaphor of what it’s like to be read. Even when somebody’s reading the book in the language you actually wrote in, it is like translation in that you cannot be standing looking over their shoulder making sure they understand everything you really meant and nothing else. You have to sort of give up this idea that you can control everything.”

Mori cautions that assessing reader response can be an overwhelming prospect. “I think I came to totally lower my expectations about how people are going to read my work once I put it out there.” She’s also selective about her own responses to what readers say about her writing. “I do read the reviews, whether they are good or bad. And I totally care what my friends think. But all my close friends are writers, so what they think about the books is different from what somebody thinks about the books who is not a writer.”

She immediately qualifies, “I’m always honored that people would share their personal stories with me about how they too had to overcome their parent’s death or suicide, but then I feel like I also need to step back from that. I’m glad that people read the books and feel that they are helpful, and I certainly wouldn’t write anything that would be hurtful.”

Jackson has joined Miles in a new search through my bag for more paper. Mori leans over to playfully shoo them away. When she turns back to me, she says, “I guess ‘do no harm’ is really kind of my philosophy about writing. I hope, in some general way, everything I do contributes to the positive energy in the universe, but the reason for my writing is that I like doing it. I like to sit down at my desk and kind of arrange things. And some days, I don’t even enjoy that. But I feel compelled to sit at the desk and rearrange things until I like the way the pattern looks. That is important to me. I hope that I’ll write things that people would find helpful, but in a way, I’m happier when people find the design to be beautiful than the content to be helpful.” She pauses. “I would feel really terrible if somebody thought I did not write well. That would break my heart. I want something beautiful in the end that I can look at and say, ‘I made that.’”

Despite the much-deserved success she’s achieved in her writing career, with seven books and numerous essays to her name, and the countless times she’s sat down at her desk to begin the process of writing something new, Mori still admits the “making” is truly the hardest part. “I continue to be surprised every time I sit down to do it how much you have to write and revise to get a book. And each time, this is the thing I have to forget. Any time I start a new book, I can’t be thinking too much about how much of what I’m writing is or is not going to be in the book by the time I’m done. Forgetfulness is great.”

I point again to my copies of The Dream of Water and Yarn and ask, “Do you ever look at these stories and ask, ‘Did I get it right?’” I’m speaking to my own insecurities now by asking this question, my fears that no matter how hard I try to recount my experience with my dad’s illness and death, I won’t ever be able to do the whole story the justice I feel it deserves.

“By the time that was the question, I think I realized that the part I had to get right really wasn’t about anyone else; it was really about me,” Mori replies. “I would never really know what my mother’s story was, or my relatives’ reaction to it, or my father’s even. The thing I had to get right was me trying to figure that all out. Once I realized that, then really what mattered was that I do my best.”

Mori seems to understand that this final question I’m asking is more about me than it is about her because she shifts to a gentle tone I imagine her using with her own writing students who are struggling to bring their experiences to the page. “These things already happened,” she says. “Whatever you do with it is yours. And if these bad things that happened in your family enable you to write a book that is going to be the ticket to the next part of your life, I don’t think that there is any guilt or shame in this, because those things already happened. While they were going on, you reacted in the way you reacted with the best of intentions, probably not always doing the right thing. And when you write the book, it will be the continuation of that. You’ll have the best of intentions, and not always do the right thing in terms of craft or in terms of the storytelling or even in terms of getting it published. But you are going to do your best, and what more can you do?”

Later that night, I replay this section of the interview when, on my flight home from DC, I relax into my window seat and pop in my ear buds to check the quality of the recording. I have plans to listen to the whole thing in the coming days, so I only rewind the last few minutes. I watch the expanse of lights from our nation’s capital disappear into the night below the clouds and allow Mori’s voice to quiet my mind. “Do your best. What more can you do?” I lean my head back against the headrest and close my eyes. There is nothing else for me to see beyond the dark out the window.

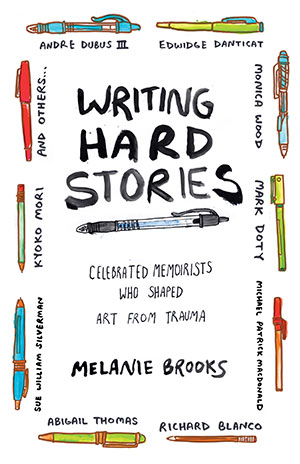

Excerpted from Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma by Melanie Brooks (Beacon Press, 2017). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Melanie Brooks

Melanie Brooks is a writer, teacher, and mother living in Nashua, New Hampshire with her husband, two children, and yellow Lab. She received her MFA in creative nonfiction from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Master’s in Fine Arts program. She teaches college writing at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, and Merrimack College in Andover, Massachusetts. She also teaches creative writing at Nashua Community College in New Hampshire.