Kristine Langley Mahler on How Online Rabbit Holes Fuel Creativity

“The looking is the creeper behavior, but the processing of those digital finds can become the nonfiction writer’s justification.”

I’ll go ahead and answer the self-deprecating Twitter question: yes, you do get to count Googling as writing if you’re a memoirist or essayist. It’s all research, baby. At the Tin House Winter Workshop a few years ago, Hanif Abdurraqib gave a craft talk about his work and straight-up advised us to follow the procrastination burrows because they can nourish the work. Go ahead and open those tabs—when you’re nurturing side questions about the material that originally brought you to the page, you’re keeping your interest alive. Always trust the author of a National Book Award Finalist, I say.

But sometimes a nonfiction writer isn’t following online rabbit holes because she’s bored—sometimes she’s deliberate. Sometimes she’s working on a piece chronicling what can be found out there. Sometimes she’s tracking the bent stems and the boot imprints and the discarded granola bar wrappers and using the retrieved information as a bolster but also as a bulletin board: do you realize what anyone can find? A mugshot, a property tax assessor search, a roster for a high school basketball team that went to the state finals in 2000. You can slough off social media, but Google will find you anyway. And then I will find you on Google. This is the essayist’s destiny in the era of Google: to write about what can be seen if one simply looks.

*

Everyone does it. We used to be so covert—we were taught to be covert with what we shared online! Remember? No first names! No last names! No locative details! They’re all old and degraded and long since disintegrated, so I can tell you my AIM name back then was daisy8girl, a moniker that revealed nothing except that I was…a girl? Who liked daisies? Maybe? The early 2000s social sites like MySpace and Livejournal also encouraged alternate identities (mindALIVE and daisygirl—I was a little fixated), but even as late as the mid-00s, I was rolling through TheKnot wedding chat boards as from*the*west (what’s up, fellow Metro Detroit brides? Remember the drama with TheRater?).

This is the essayist’s destiny in the era of Google: to write about what can be seen if one simply looks.

And then came Facebook. Damn Facebook, with its requirement that you use your real name when you set up an account. That was the beginning of the end, the harbinger of the reveals coming with Mature Google as its algorithms improved its returns. Meanwhile, all our hometown newspapers slowly crept into the 21st century and put their backlogs online. Searchability, now, is an A/S/L nightmare no one imagined in the mid-90s when we were chat-rooming it up. Nowadays, the minute you let your last name slip—online or in person—you’re on lock.

Our history’s a crumbled pile of artifacts half-buried in digital soil, an elbow-like link poking out and just waiting for someone to pluck it up from the e-archives with a click. Access to the things we didn’t intend to share has been there for a long time, ever since Google flattened a path to what we most want to know.

Which is what can be found.

*

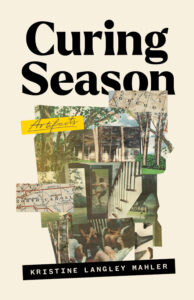

For almost fifteen years, I was absolutely terrified that my old best friend (I call her Annie in my essay collection, Curing Season, so I’ll maintain that scrim of a lie here too) would be able to find me. Annie and I had an adolescent friendship which deteriorated as she practiced normal teen behaviors like DRUGS and LYING and BULLYING and I scrambled to stay relevant to her by PRETENDING I UNDERSTOOD DRUGS and LYING TO MY PARENTS ABOUT HER ACTIVITIES and ACCEPTING THE BULLYING AS MY DUE. Annie moved away and then my family moved away and, in the mid-90s, that should have been that so far as any future interactions were concerned, but somehow she found my family’s new phone number and contacted me when we were in high school. And again when we were in college. And then I found her, but that’s a whole essay you’ll have to buy Curing Season to read.

I used to Google myself—yes, even back in 2004—to see how much access a random person could have. The returns increased exponentially if said person knew the city where I lived. So there’s one reason I’ve had my (since deactivated) Facebook and Instagram accounts private since their inception. But the second reason is because I too am a Google Creep. I’ve been Facebook-stalking and Googling my old classmates for years and years. Through the laptop screen, I’ve watched relationships turn into pregnancies turn into children turn into middle schoolers—surreal considering I knew some of their parents when we were in middle school ourselves. The existence of Google and the sloppy privacy settings of social media have meant access to personal information is, and has long been, there for anyone who has the interest in piecing it together.

I have had the interest in piecing it together.

Access to the things we didn’t intend to share has been there for a long time, ever since Google flattened a path to what we most want to know.

From the ages of 10 through 14, I lived in Greenville, North Carolina. My family had relocated from Oregon so my father could take a position teaching at East Carolina University, so when I arrived, I was a newcomer to the South. I was eager to belong to my new homeland—I’d had no personal claim on Oregon, as both my parents and I had been born in the Midwest—but I found it was impossible to feel like I belonged in the South since I had made the cardinal mistake of having no Southern kin. Still, I was always good at finding backdoor access, so I researched—well, as much as a girl could in the mid-90s.

First, I read Gone with the Wind and stored away Scarlett’s missteps like a catalog of warnings—because apparently even a homegrown Southern girl could alienate herself if she wasn’t careful. Then, armed with that intelligence, I smiled and high-kicked my way onto the middle school cheerleading team because I never forgot a step once I’d learned it; I can still perform the first half of our routine to the ECU fight song today (though my 40-year-old hips aren’t as limber as they once were). “Beep-beep bonnnnng” went the dial-up as I clicked into AOL chat rooms as TeeninNC (yes, in 1994 that was me; I nabbed it at a prescient age 12), watching how easy it was to pretend to be someone else.

I paid exquisite attention to the behaviors of others, but in the end—when we moved away from the South four years after we’d arrived—I had acquired nothing so much as a bank of the reasons I felt like I couldn’t ever belong there, no matter how much I’d wanted it. And I could not deal with my failure. As I got older and believed I was so far away from being that grasping 14-year-old girl who’d just wanted to belong (a truth I didn’t know would never go away; we never fully escape the people we were), I needed evidence that no one had really succeeded at fleshing out the life I had constructed around their perceived privilege.

A nonfiction writer keeps a lockbox of memories and she loves sifting through her saves, but a nonfiction writer also knows that accumulated dust will fur atop her sticky questions over the years. A nonfiction writer knows when the memories need a little corroboration, a little update, a little something new to either resent or reframe—a little information fortunately acquired through a little Googling.

*

I said I’d paid exquisite attention to others, and by that, I mean I also remembered just about everything about them. The names of my peers, the neighborhoods where they’d lived (if not their exact addresses), the activities they’d participated in. These became the portals I followed when Facebook and Google arrived.

A nonfiction writer keeps a lockbox of memories and she loves sifting through her saves, but a nonfiction writer also knows that accumulated dust will fur atop her sticky questions over the years.

Suddenly I could find out… a lot. Facebook had me covered with personal details: I attended quite a few weddings to which I was never invited; I also watched several relationships explode. I reveled in the shit-talk comments posted on the photo a former classmate shared of herself and her putative grandmother, where a rando hollered out, “You can stop trying to convince yourself that X isn’t Y’s. As you can see, this is a picture of X and Y’s mom. I also have DNA that Y is X’s dad and there is never any doubt in my mind who her Daddy was.” All without ever having to friend someone who—let’s be honest—was never my friend. She was just a classmate, once, with an unlocked—which is to say, non-private, non-friends-only—Facebook account.

But my good friend Google did the rest.

*

You know these facts already—you know what can be known by searching online. In the first 10 pages of Jeannie Vanasco’s memoir Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl, she Google-Street-views her rapist’s work address—a detail she found by first searching and finding him in an online forum which revealed his occupation. Ashley Marie Farmer’s essay collection Dear Damage has an entire section comprised solely of the internet comments she found—posted by others—about her grandmother’s murder. In Another Appalachia, Neema Avashia keeps tabs on an old neighbor through his Facebook posts, discovering that his recent right-wing views on immigration don’t align with the neighborly kindness she had experienced when she was a child. In Curing Season, I don’t obscure my research either. I lay out the discoveries I obtained through my creeper behavior, zooming in on houses and graveyards in Google Maps, deconstructing a family WikiTree, hunting up school board complaints. I use blog comments to bolster my work as well, and then I go lo-fi by transcribing (and modifying) printed family histories. There’s a section in one of my essays, “A Fixed Plot,” that says, “the information has always been right there, unobstructed, but it’s obvious only to those who know how to look.”

The looking is the creeper behavior, but the processing of those digital finds can become the nonfiction writer’s justification. By turning the night-vision goggles on herself, a writer has the opportunity—I say, necessity—to dissect what is being revealed about herself by both her incessant searching and by the discoveries she chooses to share.

For instance, if I am writing about a classmate who had seemed to be the epitome of what it might mean to belong in the South, doesn’t my essay gain accuracy—and poignancy—when I discover through Googling that she still lives in Greenville; that her wedding announcement included the traditional assignation of groom’s-father-as-best-man; that she and her husband vacationed on the Outer Banks; that she had two sons and named one son with her maiden name, the other son a III; that she opened a store specializing in monogrammed pillows (those monograms that drove me crazy when I lived there: First Initial LAST INITIAL Middle Initial)? When I include those details in the essay? When I show you all that I was still so desperate to prove her life did turn out like I’d expected that I was willing to go trolling through five pages of search results?

Yes, you can Google me, too. You can find the 2014 Google Maps image of my house with the sunflowers we tried growing that year, but that picture is outdated. Those baby trees have grown into a wall, allowing me to peer out from between the branches. Just scroll around to the cul-de-sac. The garage door is open because there are access-mistakes I used to make as well. I write about them.

___________________________________

Curing Season: Artifacts by Kristine Langley Mahler is available from West Virginia University Press.

Kristine Langley Mahler

Kristine Langley Mahler is the author of Curing Season: Artifacts (WVU Press, 2022) and A Calendar is a Snakeskin (Autofocus, 2023). Her work has been supported by the Nebraska Arts Council, named Notable in Best American Essays 2019 and 2021, and published in DIAGRAM, Ninth Letter, Brevity, and Speculative Nonfiction, among others. A memoirist experimenting with the truth on the suburban prairie outside Omaha, Nebraska, Kristine is also the director of Split/Lip Press. Find more about her projects at kristinelangleymahler.com or @suburbanprairie.