Korean Revolutionary Kim San on Moral Courage in the Face of Imperialist Violence

“To rise above oppression is the glory of man; to submit is his shame.”

My whole life has been a series of failures, and the history of my country has been a history of failure. I have had only one victory—over myself. This one small victory, however, is enough to give me confidence to go on. Fortunately, the tragedy and defeat I have experienced have not broken but rather strengthened me. I have few illusions left, but I have not lost faith in men and in the ability of men to create history. Who shall know the will of history? Only the oppressed, who must overthrow force in order to live. Only the undefeated in defeat, who have lost everything to gain a whole new world in the last battle.

Oppression is pain, and pain is consciousness. Consciousness means movement. Millions of men must die and tens of millions must suffer before humanity can be born again. I accept this objective fact. The sight of blood and death and of stupidity and failure no longer obstructs my vision of the future.

The tradition of human history is democratic, and this tradition is the equal birthright given to all men. But some do not claim this birthright, and others steal it from them. Water can drown or save a man. Human society today is not a village pond but an angry flood. One must learn to swim. From the age of fourteen to this moment I have never left the water. I have given myself up many times, but I am not yet destroyed.

I have few illusions left, but I have not lost faith in men and in the ability of men to create history.

I have learned that there is only one important thing—to keep one’s class relation with the masses, for the will of the mass is the will of history. This is not easy, for the mass is deep and dark and does not speak with a single voice until it is already in action. You must listen for whispers and the eloquence of silence. Individuals and groups shout loudly; it is easy to be confused by them. But the truth is told in a very small voice, not by shouting. When the masses hear the small voice, they reach for their guns. The mere urgent whisper of an old village woman is enough. True leadership has keen ears and a guarded mouth. To follow the mass will is the only way to lead to victory.

For the individual to struggle against superior power is only futile tragedy. One must organize equal force against force, and if this cannot be mobilized, action must wait and not engage in adventurism. Parties and groups and large bodies of men make many stupid mistakes leading to disaster, and I have participated in many such blunders, but mistakes are an inevitable part of leadership. You may see this mistake, but until you can win the following of the majority you have no right to leadership. To be in advance of your time does not qualify you for leadership but only for propaganda work and criticism. Lenin was the greatest democratic mass leader of our day because he followed the masses and pushed them. He did not pull them along by a string.

Yet the minority must be protected, for it is the initial instrument of change, the child and father of the majority. To stifle it is only to breed a monster. And it is the duty of every man to fight for his belief. To be false to himself is to be false to his class, his party, and his revolutionary duty. There is no place for cowardice in revolutionary leadership. No man has the right to leadership who has not strong beliefs and confidence in his own judgment. Moral courage is the essence of the revolutionary ethic.

When a revolutionary submits to being deprived of his right to exercise freedom of opinion, he is failing in his duty. And no mind is free which oppresses others. Monoliths are not built of broken stones and the weakest quality clay. They can be made only of living men and strong minds, and no mortar can hold them together except the cement of free association. Without this democracy even the feeblest clay will one day turn to dynamite. A keystone is not an arch. Without support from both right and left, it will collapse. When voluntary following turns to fearful obedience, disintegration begins.

It is not easy to be morally brave in a political party; it is easier to follow, and to shirk responsibility. To be alone on a mountaintop is pleasant; to be alone among comrades is to be lonely indeed.

The quality of moral strength, however, lies not in stubborn stupidity but in the ability to change with changing conditions. The growth of the human mind seems to be limited. At a certain point it remains static and can no longer reach out and grasp new realities but softens into a childish nostalgia for some October long past. “Old Bolsheviks” would do well to be interred gloriously with their Lenins before the next generation trims their stubborn whiskers in derision.

One must accept the vote of a given majority—but whether that majority is right or wrong, that is another question. A Lenin may be right and the whole party wrong. But when a solitary Lenin happens to be right it is because he represents the majority will of the masses, not because he is an infallible individual personally. And when the party is wrong, it is wrong because it no longer represents the mass majority under it. Where democratic expression exists, the problem of leadership is easy. Where it is suppressed, it is dangerous and difficult. A true democratic mass vote cannot make a wrong decision; the problem is how to realize this vote. The line between right and wrong is a fluid one.

In times of rapid historical change, what is right one day may be wrong within a week. The mercurial changes within a mass movement are proof of the correctness of mass judgment, for they truly reflect change, which is the essence of truth. Truth is relative, not absolute; dialectical, not mechanical. The swing from Right to Left and back again is in itself a process of reaching a correct evaluation. And that swing is also in itself a factor producing change. Men learn and reach correct judgments only by experience. To test a certain line of action is not to make a mistake but to take the first step toward discovering the correct line.

If that test proves a certain line to be wrong, the test itself was correct, was an experiment in search of correctness, and therefore necessary. There are no controlled conditions in the great laboratory of social science. You cannot throw away a test tube and start again with the same given elements. There is only one test tube, and its compound changes qualitatively and quantitatively as you watch. Everything you do or fail to do goes into that mixture and can never be retrieved.

I have not always reasoned in this way. Until 1932 I sat like a judge, mercilessly condemning “mistakes” and beating recalcitrants into line like a drill sergeant. When I saw men killed and movements broken because of stupid leadership and stupid following, a fury possessed me. I could not forgive. When Han and another Korean party leader were on trial in Shanghai in 1928, I did not care whether they were spies and traitors, but I felt earnestly that they deserved any punishment for their objective criminal stupidity in having a party organization so weak that the Japanese could arrest a thousand men in a few days.

Nothing can rob a man of his place in the movement of history. Nothing can grant him escape.

I was an idealist. I judged the actions of men by their intelligence. Now I know that a man is composed of many things besides a brain. A revolutionary leader does not work with human skulls, to be lined up Right or Left. He works with the material of human life, with all its animal and vegetable characteristics, with all its variable and imponderable attributes. He works with the human spirit, so hard to crush, and with the human body, so easily destroyed. Often the body must be destroyed to waken and free the spirit of others. The execution of one man like Li Dazhao or Peng Pai may mean the awakening of a million.

For myself, I no longer condemn a man by asking what is good or what is bad, what is right or what is wrong, what is correct or what is mistaken. I ask what is value and what is waste, what is necessary and what is futile, what is important and what is secondary. Through many years of heartache and tears, I have learned that “mistakes” are necessary and therefore good. They are an integral part of the development of men and of the process of social change. Men are not so foolish as to believe in words; they learn wisdom only by experiment. This is their safeguard and their right. He knows not what is true who learns not what is false. The textbook of Marxism and Leninism is written not in ink but in blood and suffering. To lead men to death and failure is easy; to lead men to victory is hard.

Tragedy is a part of human life. To rise above oppression is the glory of man; to submit is his shame. To me it is tragic to see millions of men blindly give up their lives in imperialist wars. That is waste. It is tragic to see them utilized to oppress each other. That is stupidity. It is not tragic for men to die consciously fighting for liberty and for the things they believe in. That is glorious and splendid. Death is not good or bad. It is either futile or necessary. To be killed fighting voluntarily for a purpose in which you believe is to die happy. I have seen so much waste of human life, so much futile sacrifice ending in failure, that it has not been easy for me to reach a philosophical justification for this. But one thing I always remember—the revolutionaries died happy in their sacrifice; they did not know it was futile.

One man’s happiness is another man’s sorrow. I claim no right to it.

Nearly all the friends and comrades of my youth are dead, hundreds of them: nationalist, Christian, anarchist, terrorist, communist. But they are alive to me. Where their graves should be, no one ever cared. On the battlefields and execution grounds, on the streets of city and village, their warm revolutionary blood flowed proudly into the soil of Korea, Manchuria, Siberia, Japan, and China. They failed in the immediate thing, but history keeps a fine accounting. A man’s name and his brief dream may be buried with his bones, but nothing that he has ever done or failed to do is lost in the final balance of forces.

This is his immortality, his glory or his shame. Not even he himself can change this objective fact, for he is history. Nothing can rob a man of his place in the movement of history. Nothing can grant him escape. His only individual decision is whether to move forward or backward, whether to fight or submit, whether to create value or destroy it, whether to be strong or weak.

__________________________________

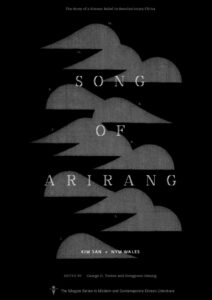

From Song of Arirang: The Story of A Korean Revolutionary in China by Kim San and Nym Wales (translator). Edited by George O. Totten III and Dongyoun Hwang. Copyright © 2024. Available from Kaya Press. Featured image: Nym Wales

Kim San

Born in 1905, Kim San (Jang Jirak) left his family in Korea as a teenager and crossed the border into China, where he joined Mao’s Red Army. A participant in or witness to some of the most critical events of the Chinese Revolution, he became a leader in the fight against Japanese colonial rule, and was executed in China in 1937. He was awarded a posthumous “Patriot” award by the South Korean government in 2005.