Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham on Social Media, Black Futurity,

and the Archive

"Black Futures started as all great contemporary love stories do—on an app!"

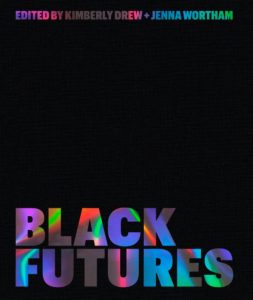

Writers Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham have edited and brought forth to the world Black Futures, a visually-stunning mixed-media anthology that threads together different facets of Black culture and thought by some of today’s most esteemed poets, artists, academics, and creatives. At its heart, the book seeks to answer the question “What does it mean to be Black and alive right now?” Yet, throughout the course of the book, we are not necessarily offered answers but capacious openings that showcase the beauty of Blackness and the imaginative possibilities of our futures. Below, Drew and Wortham answer a few questions about their work.

*

Rasheeda Saka: Could you tell us a bit about how Black Futures came to be?

Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham: Black Futures started as all great contemporary love stories do—on an app! Back in 2015, we connected over Twitter DM and began to ideate on what it would mean to create a multimedia project that could get its arms around some of the cultural flourishing across intersections that we’d observed online and in the world. We were initially inspired by Beyonce’s inclusion of popular Youtuber Evelyn From the Internets during her 2016 Formation Tour. It was an incredible moment of connectivity, and acknowledgment and co-creation that would foreshadow the social media world we live in now. But back then it felt revelatory! We asked ourselves: How could a media project conserve and make available some of the beautiful and undeniably important conversations, cultural contributions, and more that were being shared over the Internet? The project evolved from there, and began to emerge as a time capsule, a blueprint, a map and a resting place for our generation’s responses to the cultural, ecological, social and artistic revolutions of our time.

RS: Online, there exists an inherent tension between remembering and forgetting that is particularly tormented, given how little agency we have over how information and memories are stored. How does this reality inform or shape Black Futures?

KD + JW: It’s safe to say that we are all in a love/hate relationship with social media and our devices and yet, it is impossible to ignore the incredible ways that social media has served to create connections that drive us, inform us, entice us, and challenge us to be more curious about our own beliefs. With this in mind, we must also remember that all too often Black culture is at the risk of erasure or co-option. As co-editors of this anthology, we wanted to create a project that could counteract the forces of white supremacy and also inspire a generation of Black folks to see ourselves as we are right now, as we might have been, or how we could be if we were able to sit and love on ourselves with intention. We all have the agency of remembering and holding dear what feels most valuable to each of us. This book is our attempt at enacting that agency.

RS: Many writers—Saidiya Hartman, for example—write about the violence of the archive and the impossibility of recuperating much about Black life from it. In that vein, what does the archive mean to you and for this project?

KD + JW: We had a keen awareness that all archives are incomplete because they rely on the priorities and preferences of the authors and collectors, and relied on the wisdom of Dr. Hartman to guide us as we embarked on our efforts. We see our efforts largely as a rebellion against the ephemerality and overload of social media. We know one book is not enough. Inherent to the ethos embedded within “Black Futures” is (hopefully!) inspiring our readers to document our present as they see fit, too.

RS: I see that Black Futures is acutely attuned to questions of history and time. In particular, I’m thinking about Alisha Wormsley’s “There Are Black People in the Future” and Rasheedah Phillips’ piece on time and memory. How are you thinking about futurity? And what does this mean for us in terms of how we engage with our past?

KD + JW: In their own way, both of those pieces encourage Black people to start creating their own temporality and frameworks for time beyond what we have inherited. In Dr. Michelle M. Wright’s book “Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology,” Dr. Wright outlines the ways in which Blackness is constantly evolving and updating itself, expanding and stretching in ways that don’t fit into the epistemology of our current historical framework. Dr. Wright asks that we consider ourselves in relation to each other, rather a relationship to a fixed point in the past (or the future) and our book orients itself the same way, which is why it is non-linear and not tethered to a chronology of any sorts.

RS: Perhaps for good reason, it seems that there has been a rising number of folks who have grown cynical about the concept of joy since (as they argue) it is always structured by the violence of the systems in which we live. Do you think Black Futures has a response to this kind of affective turn? And how have you held on to joy and hope during 2020, with a pandemic, national protests, presidential election, and all?

KD + JW: All of these ideas are bound up in a piece by the filmmaker Arthur Jafa, whose work “Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death” is featured in Black Futures. The film is a love letter to Black people, it is also a dirge, it holds in both hands the very tension you mention between joy and violence, and how the two always seem bound in an unholy binary for Black people.

The film moves seamlessly from President Obama singing “Amazing Grace” during the eulogy for Rev. Clementa Pinckney, who was killed in the 2015 shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston to his daughter’s wedding day, from Black bodies writhing with pleasure at a party to being manhandled by the police. Watching that film fills you with sorrow and pride, it puts a feeling to what is so hard to articulate in words. We’ve found hope in the mutual aid efforts that have formed sustainable frameworks of help and care, and in the 15,000 people who turned up for the March for Black Trans Lives in June in Brooklyn. We are constantly in awe at the work people are making that capture the intangible feelings of our existence and the real-world ways people are resisting neglect and governmental disregard in the wake of the pandemic.

__________________________________

BLACK FUTURES, edited by Kimberly Drew + Jenna Wortham, is available now via One World.

Rasheeda Saka

Rasheeda Saka was Literary Hub's 2020 fall-winter editorial fellow. In 2018, she was named one of Epiphany Magazine's Breakout 8 writers for her short story "The Killers' Den." Her work has appeared in Alta Online, Literary Hub, and TriQuarterly.