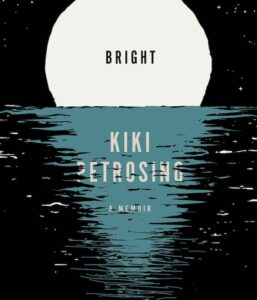

Kiki Petrosino on Race and Where “Brightness” Begins

Telling the Story of an Interracial Family

You don’t need white people’s approval to be happy, the Mirror said. But if you want anything from their world, they have to like you.

*

Bright is an American slang term for light-skinned people of Black & white ancestry. It’s not a compliment.

From an early age, I understood how bright applies to me, to my skin, to the face I show the world. I’m fair for a Black girl. Powdery-pale, especially in winter.

It’s hard to love bright. The sly, knowing way its lone syllable sidles up. Bright gets too close too soon, thinking it knows all about me. To be frank, there’s a mean smile in the word.

Light, bright, & damn near white, goes the rhyme.

Fuck those light brights, goes another.

As soon as I enter the classroom, as soon as I put my books on the lectern, as soon as I begin speaking, those who don’t like bright don’t like me, & I can feel it.

So what?

*

I was born in 1979, in Baltimore City, to a Black mother & Italian American father.

As Catholics (my mother having converted before my birth), they sent my sister & me to parochial schools.

At Immaculate Conception School in Baltimore, I turned the pages of a picture book about ladybugs beneath a bower of white-gold honeysuckle.

Some of the older girls taught me how to draw a single drop of nectar from the stem’s fine filament & place it on my tongue.

Part of my Brightness begins this way.

*

In the mid-1980s, we moved to Shrewsbury, Pennsylvania, then a small, nearly all-white town just north of the Maryland line.

Back then, I believed in my own unworthiness as deeply as I believed in the Holy Trinity.

My parents built our new house in a development carved from seemingly endless farmland. Instead of a garage, they added an extra family room to our three-bedroom ranch house with its gray aluminum siding & burgundy shutters.

It was to be a house for sleepovers & summer barbecues, for holiday parties lasting far past bedtime. For months after we moved in, the house smelled like plaster, paint. The sharpness of fresh earth.

My parents loved southern Pennsylvania: its clear air, its country charm. It must have felt, to them, like an escape from the city. On weekends, they bought Amish potato rolls from the farmer’s market & took us to nearby Dutch Wonderland, an amusement park composed entirely of kiddie rides.

What I remember: how the house spread horizontally across our quarter acre, while everything in Baltimore had been stacked high & close. Most of our neighbors in Shrewsbury were Catholic; we saw no other Black or interracial families.

Our Brightness was new, here.

*

Here’s how the plan for our family worked:

Each weekday morning, my parents got into the family car & commuted an hour from Shrewsbury back down to Baltimore to teach in the City schools.

My sister & I, in matching plaid uniforms, our braids tight on either side of our heads, took the bus in the opposite direction, to a small Catholic school where we were two of the only Black students in the building.

On the bus, we often held hands, even across the aisle, only unclasping when another kid boarded.

From the bus windows, I would watch the dawn mist, its huge angelic presence, rising from rural fields of green & manure-black. The barns we passed along the road were decorated with the stylized goldfinches, rosettes, & pineapples of the Pennsylvania Dutch.

What it meant: abundance, welcome, good luck.

*

When I first heard the name, Pennsylvania, I imagined we were moving to a house made of pencils. We ended up in a suburb just emerging from rural landscape.

Our street had no sidewalks, no parks or green space, only concrete gutters leading to storm drains, each one stained orange with clay. Neighbor to neighbor in this suburb, we glimpsed each other mostly through car windows on our silent, collective way to Elsewhere: groceries, church, the mall.

On summer nights, I could discern the promise of rain, as if it were a feeling inside my body. Secretly, I would open my bedroom window, touching my tongue to the metal screen. Crabgrass & vetch spread over the backyard, like fists clenching & opening.

When he visited the ranch house that first year, my Italian grandfather spent hours breaking up the stubborn clumps of reddish soil, heaving a pick over his head & bringing it down for marigold beds.

Only reluctantly did the earth accept what we planted.

*

She looked down & noticed her own thighs: uneven fields, dug out with tiny spades.

*

There’s a loneliness in being called the N-word, in being called zebra & darkie, in rooms with saints’ images on the walls, in spaces where we all prayed the rosary, bead by bead.

My sister & I forged a pact to get through recess: we would keep an eye on each other. If one of us ever saw the other alone, we would leave our game & come over immediately.

More than once, I remember my sister soundlessly appearing at my elbow, her face an orbiting moon of worry resembling my own.

For two weeks a year, on the hinge of summer & fall, my Italian grandparents would visit. Each of those days, Grandpa collected us at the bus stop, on foot, wearing his plaid flannel work shirts & jeans, fresh from the yard.

Even before Pennsylvania, there was something I didn’t like about my mouth, my teeth. It wouldn’t go away.

All the teasing, all the screaming taunts from the bus—they ended when Grandpa arrived. He walked us back to the house, slowly, in view of every neighbor on that street, each of his hands holding one of ours.

*

I don’t know how to explain Pennsylvania, how it changed the story of my Brightness.

How I sat alone at lunch each day. How I started choosing the end seat, so as not to be marooned by empty chairs in the middle (I still do this). Back then, I believed in my own unworthiness as deeply as I believed in the Holy Trinity.

With a desperate pull in the chest—this is how I yearned for kindness from the teachers who lined us up on picture day. Teachers who, if someone’s hair was out of place, would gently swoop it to one side with a plastic comb that was, then, that student’s very own to keep.

When that teacher came to me—my hair erupting from its braids in a crazed halo—she would only sigh & say, “I’m afraid to even touch this,” before turning her back.

Always, just at the edge of my vision, the white world burst into ecstatic blossom: girls sharing snacks & going to birthday parties, girls talking all night on the phone. I imagined what it would be like to go to a friend’s house after school, the feeling of being gathered up, by a friend, into a sudden hug.

Decades later, my eyes still move across the calendar to the loftier girls’ birthdays: April. May. June.

Abundance. Welcome. Good luck.

*

When my sister & I drew in our coloring books, my mother always joined in, selecting crayons from our communal box.

I noticed how she filled every human face with complexity, blending brown & reddish shades, leaving the pale “flesh” crayon to languish alone. To flip through her coloring book was to glimpse a world full of variation. A place of tenderness & protection, where brown angels hovered over sleeping forest animals.

Late afternoons back then, I stood before the full-length mirror at the end of the hall & stared into its dim surface. Even before Pennsylvania, there was something I didn’t like about my mouth, my teeth. It wouldn’t go away.

Part of my Brightness begins here, too.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Bright by Kiki Petrosino, available via Sarabande Books.

Kiki Petrosino

Kiki Petrosino is the author of White Blood: a Lyric of Virginia (2020) and three other poetry books. She holds graduate degrees from the University of Chicago and the University of Iowa Writer's Workshop. She teaches at the University of Virginia as a Professor of Poetry. Petrosino is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize, a Fellowship in Creative Writing from the National Endowment for the Arts, an Al Smith Fellowship Award from the Kentucky Arts Council, and the UNT Rilke Prize.