Kathryn Davis on Bingeing Lost and Coming to Terms with the Unknowable

“There is unearthly howling. There is a hatch leading who knows where.”

There is the moment you step off the edge of the cliff before you hit the ground. The moment you open the door before you step inside. This moment can last a second or it can last a lifetime. “They heard the two horses munching leaves.” A paragraph that is a single sentence swells to occupy all the space between the moment Rodolphe puts his arm around Emma Bovary’s waist and the moment he leads her deeper into the woods. Between “And I will show you something different from either / Your shadow at morning striding behind you / Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you; / I will show you fear in a handful of dust” and “Don’t tell me what I can’t do.”

The experience of leaping into space is a thrilling one. You leave the page behind and if you’re lucky you’re granted access to the mind of the person who wrote what was on it. Certain art forms—literature, music, film, the ones that exist in time or take time for their subject—lend themselves to this experience. Jean Seberg in a convertible without a mirror, Jean Seberg in a convertible with a mirror. An ape throws a bone in the air, a space satellite rotates back. The wild leap Beethoven makes from sweetness to discord at the end of Opus 134. And there you are, ghostly you and the ghostly artist, in ghostly communion in that non-existent place between words, images, notes.

A Buddhist calls this period of transition a lifetime, the great transition between birth and death.

I came late to Lost. The show first aired on September 22, 2004; I didn’t start watching until the spring of 2009. I’d been told I would love the show by people who knew me well enough to know my preference for the enigmatic. Sometimes, before I began to watch, I would overhear conversations about Lost and I remember experiencing a feeling of curiosity akin to longing. I was told The Third Policeman makes an appearance during the second season. I was told Eternity did too.

Sometimes, before I began to watch, I would overhear conversations about Lost and I remember experiencing a feeling of curiosity akin to longing.

Time passed and, as so often happens under these circumstances, things changed. My husband—not the husband of the Greek island—was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer and had to undergo surgery. There were post-surgical complications; it was obvious we needed something to distract us from everything else that was going on. In other words, we needed something to watch. By this point the first three seasons of Lost were available on DVD. It didn’t show up on Netflix until much later.

Even if you’ve never seen the show you probably know the premise: It starts with a scene of catastrophe, the wreck- age of a large airplane—Oceanic Flight 815—on a beach. People are wailing, pieces of fuselage are in flame, a man gets sucked into a still-whining jet engine. It’s unclear where this is, exactly, and it’s unclear what brought the plane down, though while a plane crash is not an everyday occurrence, there is nothing especially otherworldly about such a thing. It’s only gradually that we begin to see that the place where these people find themselves isn’t the predictable tropical island paradise it first looks like. Beating through jungle underbrush they come upon a polar bear; an animate cloud of smoke that is really a monster pours forth from a bamboo forest. There is unearthly howling. There is a hatch leading who knows where.

What I found most compelling about Lost is the same thing that came to turn off many of its viewers, even its so-called die-hard fans. After a while the delectable inexplicability of everything about the island, starting with the polar bear and the smoke monster and continuing through weeks of characters disappearing without a trace (young Walt), characters appearing as if from out of thin air (Daniel Faraday), characters miraculously cured (John Locke), characters dying and reappearing (Boone Carlyle), the popping up of clues (The Third Policeman!), the popping up of clues that ultimately led nowhere (characters named Locke and Faraday and Carlyle and Rousseau and Hume), of mysterious recurrence (the numbers 4 8 15 16 23 42 showing up as the serial number for the hatch and Hurley’s winning lottery number, as well as being the numbers that won the Mega Millions lottery for 41,763 Lost fans and the coefficients in an equation that predicts the end of life as we know it), and, finally, of the growing suspicion that the creators of the series (Damon Lindelof, Carlton Cuse, Jeffrey Lieber, and J. J. Abrams) never had an explanation in mind for why and how a particular group of people managed to survive a plane crash that was impossible to survive (in which the entire tail section of an aircraft broke o/ midair)—after a while all of this delectable inexplicability began to drive people, and not just denizens of the island, crazy.

The thing about cancer is that it seems bestowed haphazardly, the system governing its bestowal as inscrutable as the system prevailing on the island.

A series like Lost—any television series meant to be watched over a period of time—involves built-in, inevitable moments of transition, moments that can last as long as or longer than a week between episodes, or as brief as the instant it takes a binge watcher to switch from one episode to the next. During these moments you think you’re leaving behind the tropical island you’ve gotten lost on and reentering whatever constitutes “real life,” the interminable dark and seesawing ramp of the hospital parking garage, for instance, or the cramped room in which you sit surrounded by the bright young faces of your husband’s medical team. The only difference is that the parking garage and consultation room have now become liminal space, places of transition where time behaves differently, where the ending—if even a thing like an ending exists—is unknown, where neither the number stamped on your parking garage ticket nor your husband’s PSA number will come to mean what you think they do.

The thing about cancer—about any human malady that doesn’t have a knowable cause (not like bubonic plague, say, or rabies)—is that it seems bestowed haphazardly, the system governing its bestowal as inscrutable as the system prevailing on the island. Routinely you feel like some rational explanation is approaching from very far off, on the horizon, something you might end up being able to see, like the freighter Kahana, something that appears to be coming to save you but turns out to be bent on doing the exact opposite and has to be blown up. All appears to be lost—Lost!—and then someone in a mysterious station that has only recently made an appearance on the island turns a giant wheel.

Think of the island as a record spinning on a turntable, we’re told, only now, that record is skipping. Whatever happened down at the Orchid station . . . I think . . . it may have . . . dislodged us. Dislodged us from what? someone asks. From time, we’re told.

Thin air, nowhere, without a trace, impossible to survive—all of these are key words and phrases, as is the end of life as we know it. From “time present and time past” to “time past and time future.” From “two horses munching leaves” to “go go go, said the bird: human kind cannot bear very much reality.”

_____________________________

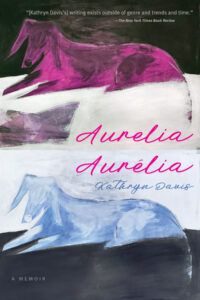

From Aurelia, Aurélia: A Memoir by Kathryn Davis. Used with permission of Graywolf. Copyright 2022 by Kathryn Davis.

Kathryn Davis

Kathryn Davis is the author of eight novels, including The Silk Road and Duplex. She is the senior fiction writer on the faculty of the writing program at Washington University.