Kathleen Boland on Getting Lost (as a Writing Practice)

“I didn’t find myself. Instead, I found an obsession.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

The advice to “write what you know” presumes you know what you know. From Jesus to Wordsworth, people wandered into the wilderness in hopes of communing with a greater power, to be forced to confront their truest selves. Get lost to get found: it’s a whole romantic thing, deeply American, inspiring everything from Manifest Destiny to the national parks. But that was back before computers had mapped every valley and cataloged ever face. ln in our digital age, is it even possible to get lost anymore?

The most lost I’ve ever been was in a Utah slot canyon. I was twenty-three. I was alone, arrogant, and underprepared. I told everyone I was headed out to the desert to “find myself.” I left Denver and drove to the Escalante-Grand Staircase National Monument in Utah. I parked near what I thought was a trailhead. (It wasn’t.) I backpacked out down a wash and set up camp next to what seemed like a stream. (It wasn’t.) I headed out in the supposedly right direction of a well-known natural amphitheater. (Have you caught on? It wasn’t.) It took less than an hour of hiking for me to realize my mistakes. There was no cellphone service, and I had none of the backcountry gear the desert requires. It was hot, my boots were too small, and I ran out of water.

By nightfall, I was terrified. I climbed onto a small rock out-cropping, hoping to catch sight of headlamps or fires. Instead, I saw two rattlesnakes and one flash of lightning. When a rock climber appeared the next morning and asked if I was alright, I laughed. He helped me back to my camp, which ended up being less than a half mile away. I couldn’t believe it, though the rock climber could. He’d grown up in the area and seen plenty of people like me. I was lucky, he said, especially since there were storms in the area. When I got back to Denver, I told friends and family I forgot to check the weather, which was true. It took me years to admit just how lost I had been.

After that trip, I read everything I could about Southern Utah. I made excuses to visit. I moved to Louisiana, but the desert still appeared in my writing, popping up in stories and characters. I would recite facts about Utah to unsuspecting friends. Did you know about the Zamboni? Did you hear about the Mormons who posed as Native Americans? That terrifying night had transformed me, but not in the way I had expected. I didn’t find myself. Instead, I found an obsession.

I’ve discovered most of my obsessions while being lost.

I’ve discovered most of my obsessions while being lost. The premise of my novel, in fact. It was a difficult fall. I had just moved to Portland, Oregon and lived the basement of a mold-filled Victorian. My roommates were two couples, who were nice, but seven years younger, and we were in phases of life where the age difference mattered. They were fresh out of undergrad, best friends and first loves, working entry-level office jobs that gave them optimism and health insurance. I was close to thirty, single, and trying to justify moving across the country for a part-time internship.

I had an unfinished novel manuscript and no friends. They lived upstairs in rooms with windows and closets. My room in the basement was a badly retrofitted laundry area home to dozens of spiders. My nights were filled with the thumping of someone else’s dirty clothes and the feeling of something skittering across my leg. Insomnia quickly became a fact of life. Most nights, I would drink lukewarm wine in bed and try to get lost. Specifically, online.

I would look up the Wikipedia page of whatever first came to mind, topics like “dew claws” or “Madonna” or “stratocumulus,” and then click through linked pages until I found a topic interesting enough to forget about the spiders. I played this game every night for weeks, hours upon hours of browsing, but there was only the one page I remember: Forrest Fenn. A wealthy man from New Mexico who buried his fortune, wrote a poem of how to find it, and sparked an honest-to-God treasure hunt. People were obsessed with him, people stalked him, people died because of him. This actually happened. Look it up. When I did, it wasn’t just a lightbulb, it was spotlight. I could see it all, finally.

From that moment on, I knew how to write the book. I finally realized what was possible. It was thrilling and invigorating. I was lost, but I was alive. I started writing again. I got a full-time job. I moved out. Eventually, after a few years, still buzzing from that revelatory night, I finished the novel.

I thought I knew how to backpack in canyon country. I thought treasure hunts only existed in children’s books. Wrong on both accounts. If I hadn’t gotten lost, hadn’t wandered into the wilderness of Wikipedia or the desert, would I ever have known how wrong I was?

What happens when you step away from the known, or what you think you know? Because of the internet, there’s the assumption that every question is searchable, every place is viewable, and every person is findable. This is not true, and never will be. Perhaps this is the prerogative of the writer, to go left instead of right, to click instead of scroll. If you assume the internet, just like the world, is a conquerable and knowable place, then you exempt yourself wonder. And there is no art without wonder. As writers, we must not only believe wilderness still exists, but also cultivate it. Writing what you know is safe, but writing while lost is sublime.

So, go get lost. Maybe I’ll see you out there.

______________________________________

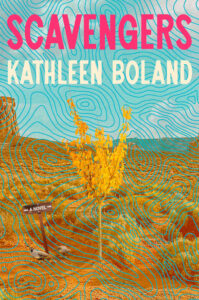

Scavengers by Kathleen Boland is available via Viking.

Kathleen Boland

Kathleen Boland’s fiction has appeared in Tin House, Conjunctions, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere, and she has received support from the Tin House Summer Workshop, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Vermont Studio Center. The former event director for Catapult/Counterpoint Press/Soft Skull Press, she earned her MFA from Louisiana State University, where she received the Robert Penn Warren Thesis Award.