Kate Beaton Applies Her Graphic Genius to the Tyranny of Babies

The Hark, a Vagrant! Creator Knows Her Audience

“Bam! Pow! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!” That headline has been appearing in mainstream publications for decades—so much so that it’s become an Onion joke. News outlets are, somehow, always surprised that comics are a medium for adults as well as kids, even though award-winning, best-selling comics for adults are by now a fixture of the publishing landscape. Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991); Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (2000), Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (2006); works by Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, the Hernandez Brothers—it doesn’t seem to matter. Comics are still associated with kids.

The fact that comics are linked with children has made some comics artists and publishers defensive. Paul Pope reports that he was told definitively by an editor at DC comics, “We don’t publish comics for kids. We publish comics for 45-year olds.”

But while some folks may yearn for adult cachet and dollars, others are less shy of the form’s juvenile past. Kate Beaton is one example. She’s best known as the creator of the online comic Hark, A Vagrant!, which focuses on such mature topics as Jane Austen’s angst and bad Wonder Woman. Though the strip is ostensibly for adults, my 12-year-old fell in love with it immediately, and I’m sure he’s not the only under-16 fan out there. When Scholastic approached Beaton about drawing books for kids, the move seemed natural. “When they asked if I had an interest in picture books, I jumped at it,” she told me by email. “Who doesn’t?”

Beaton’s first children’s book, The Princess and the Pony, was released last year—a tale of a young princess who yearns to joust, and her tiny wall-eyed farting pony who prefers to cuddle. Beaton’s new book, King Baby, is set for release on September 13th. It is, appropriately, about the dictatorial power of infants. “Your king also has many demands!” declares the crowned pudgy plush toy-like baby, leaping dramatically, limbs outspread. “FEED ME! BURP ME! CHANGE ME! BOUNCE ME! CARRY ME!” The kid might add, “DRAW FOR ME!” Comics artists must also bow to the king.

From King Baby, Kate Beaton

From King Baby, Kate Beaton

Creating for kids isn’t quite the same as creating for adults, according to Beaton, but there are similarities. “You definitely approach adult content and kid content differently,” she said, “but in both cases it’s about knowing your audience and trusting how smart they are and how much they will pick up, so in that way it’s not different. And kids are very, very smart. They just haven’t the backlog of experience behind it yet.”

Beaton says her influences as a picture book creator include contemporaries like Carson Ellis, Jon Klassen, Matt Forsythe, and Vera Brosgol. She also points to Arnold Lobel, Quentin Blake—and, of course, to Maurice Sendak. “Haven’t we all read Where the Wild Things Are a million times trying to understand the perfect equation that it is?” Beaton says. “Yet it’s reading about Sendak the man that is more inspiring to me than a lot of his work somehow. He always gave kids the credit for being smart enough to get the tough things.”

Sendak was himself strongly influenced by comics art. In the Night Kitchen, which famously includes an entirely naked and anatomically correct young protagonist—is a tribute to the visual style of Little Nemo creator Winsor McCay.

From In the Night Kitchen, Maurice Sendak

From In the Night Kitchen, Maurice Sendak

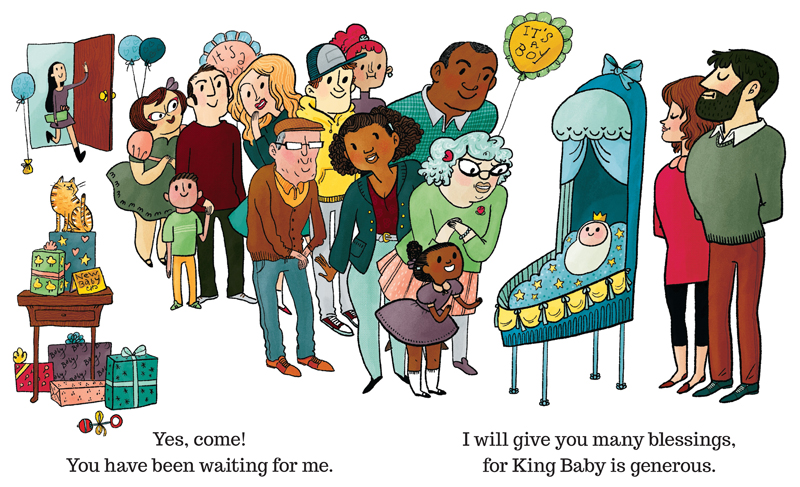

Comics these days are often most associated with superheroes like Captain America and Superman who whoosh across movie screens in pursuit of truth, justice, and so on. Sendak, though, is an iconic reminder of the fact that many of the most popular comics art is, and has always been, snuck away in those picture books. Mo Willems delightful Elephant and Piggie series, for example, looks a lot like a comic, with its speech bubbles and cartoony style, and the same goes for the wonderful work of Satoshi Kitamura . The line between comics and children’s books has always been smudged, as creators like Kate Beaton scuff over it from one side to the other and back, quite consciously. One of the loveliest sequences in King Baby in fact is a two page spread showing King Baby crawling then walking about the yard, getting more toddler-like as he goes. His perambulations are marked by a dotted path taken from many a Family Circus comic, tracing his progress from flower-bed to sandbox to toy horse, with the cat following along.

If the form of comics and children’s books blur into one another, it’s no surprise that the audiences are similarly mashed together. Comics can be for adults or kids—and children’s books are for adults and kids as well. That’s certainly the case with King Baby. The picture book is told in the voice of the infant, based on Beaton’s nephew Malcolm. But the plot is meant to appeal to Malcolm’s beleagured and exhausted parents as well. I think a good picture book appeals to both [parents and children],” Beaton told me: I mean, it’s the parents that have to read it, right? You find a lot for kids in a Chuck Jones cartoon but the thing that makes them great is how much is there for adults too without taking away what is there for kids. So yes, the overlap is definitely appealing. ”

“And in this case,” she added, “I couldn’t really help but talk to adults too, because I’m surrounded by friends and siblings with babies, and that perspective is so strong in my life right now, the lives suddenly changed forever by a new arrival.”

From King Baby, Kate Beaton

From King Baby, Kate Beaton

For Beaton, and for many other creators, comics’ connection to children isn’t an obstacle to be overcome, or a surprise. It’s a resource. Thanks to the history of crossover, comics folks can make comics for adults, children, adults with children, or King Babies with adults. Children aren’t a burden on comics, but an opportunity, an audience, and an inspiration. As King Baby forthrightly declares from his crib surrounded by cooing relatives, “Yes, come! You have been waiting for me. I will give you many blessings, for King Baby is generous.” That’s a message to happy parents, but also to comic artists—and to Kate Beaton herself, who has drawn some aunt who looks a bit like herself coming through the door in the background, looking very pleased to be in a children’s book.

Feature photo by Stephen Rankin.

Noah Berlatsky

Noah Berlatsky edits the online comics-and-culture website The Hooded Utilitarian and is the author of the book Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-48.