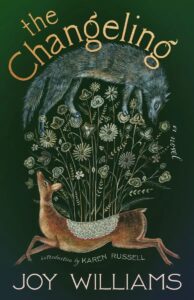

Karen Russell on the Mystery and Magic of Joy Williams’s The Changeling

“If you think your in-laws are difficult, these people will make your next Thanksgiving feel like a pleasure cruise.”

Almost half a century since its first publication, The Changeling feels at once unprecedented and eerily familiar. Readers who discover Joy Williams’s astonishing second novel in 2018 may be surprised to feel a primordial déjà vu; a tingling where their own antlers might have been, once upon a time. If The Changeling speaks lucidly to the madness of our spiritually famished, ecologically imperiled present, this resonance feels almost incidental to a deeper, timeless power. Every great book shapeshifts with its reader.

The Changeling, however, does something wilder still: it generates its own autonomous magic, one that feels wholly independent of the reader and her moment. The spirit inside it is not the human spirit—it is far vaster than that. Critics get a little nervous, I think, when their breath fails to fog up the glass. But it would be a mistake to read this book looking for the outline of your own face. The Changeling is not a mirror: it’s a window. It is refreshingly, transgressively uninterested in reflecting the familiar dramas of human life, or reproducing the conventional grammar of human thinking. Instead, its language opens a portal into the “cold, inaccessible depths.” Its project is annihilating transformation.

Ovid, Shakespeare, Morrison, God: like these authors, Williams is interested in metamorphosis and “the monstrosity of salvation.” Her sentences themselves have a cartilaginous magic. They come glinting out of profound and mysterious depths, slipping quickly through the deadening nets of any easy understanding. At one point Pearl, the novel’s protagonist, says of her own life: “It avoided meaning as the bird does the snare.” Bafflingly little has been written about The Changeling, but perhaps that critical silence is in fact evidence of its shimmering success, on its own animal terms. Like a fish from a fairy tale, a bouquet of hooks threaded through its lips, The Changeling keeps evading capture.

Rikki Ducornet considers The Changeling to be Williams’s greatest novel. Kate Bernheimer—this book’s evangelist and godmother, who heroically midwifed it back into print in 2008 for the Fairy Tale Review Press—calls it “one of the most astonishing and important works of the twentieth century.” It’s tempting to want to scold two generations of readers for more or less ignoring an obvious masterwork. But that move has always struck me as a little goofy in an introduction, like the teacher who delivers her lecture on punctuality to a bunch of empty seats. Reader, let the record show: you’re here.

Williams’s novel is concerned with time’s tyranny.

It’s also tempting to say that The Changeling was “ahead of its time.” Spatial metaphors about time make me a little nervous—there’s a suspect teleology built into them, and an unwarranted optimism about human evolution. I think this assessment gives our species too much credit. We are never going to “catch up” to Joy Williams; she is a unique instance, a true star in the firmament. And The Changeling will never be an old story, not even at the century mark. This is a young tale; its landscape is the womb of the world, its language is perennially green, and the only thing I can say about it with absolute conviction is that your encounter will surely be very different than my own.

The Changeling arrives disguised as the story of a young mother on the lam: “There was a young woman sitting in the bar. Her name was Pearl. She was drinking gin and tonics and she held an infant in the crook of her right arm.” Significantly, the booze precedes the infant in that sentence. His name is Sam; he is two months old. We seem to be in a world we know well, the world of crushing same-ness: parking lots and pretzel logs, homogeneous Florida retail. It’s a costume the novel wears for about a paragraph and a half, then shrugs off with one spectacular gesture:

Outside it was Florida. Across the street was a big white shopping center full of white sedans. The heavy white air hung visibly in layers. Pearl could see the layers very clearly. The middle layer was all dream and misunderstanding and responsibility. Things moved about at the top with a little more arrogance and zip but at the bottom was the ever-moving present. It was the present, it had been the present, and it was always going to be the present. Pearl was always conscious of this. It made her pretty passive and indecisive usually.

So much for first impressions. In an instant, our shaky courtroom sketch of Pearl the flighty young mother, Pearl the drunk, gets burned up and eclipsed by Pearl the mystic. Williams introduces us to a woman who is pierced by the clarity of her vision. Minute to minute, one melting ice cube to the next, Pearl is abysmally aware of the disintegrating present and the “encircling never.” Her passivity, if you want to call it that, can be read as evidence of the paralyzing acuity of her understanding. Pearl the mother has become Pearl the seer, and what she sees is time.

If you think your in-laws are difficult, these people will make your next Thanksgiving feel like a pleasure cruise.

Williams’s novel is concerned with time’s tyranny. We live under its sorcery, trapped by a sort of Looney Tunes physics: we’re heavily burdened by our substance-less memories, while equidistant at every instant from an imaginary future. Straitjacketed inside the inescapable present, Pearl gapes up to discover that her husband, Walker, has found her; Walker was always going to find her. If early on Pearl saw Sam’s father “with her heart,” she now arrives at the dismaying view that he is “more surgeon than husband, the surgeon with whom one would go into one’s last, unsuccessful operation.”

Walker has come to drag his wife and son back “home,” to a private family island in the North Atlantic, ringed by mists and ruled by Thomas, Walker’s pale, angry doppelgänger of a brother. Some of the novel’s most luminous and haunting writing occurs in the passage from the mainland to the island, in which we feel Pearl’s selves foaming away, one after another

As they headed out, the sky turned slowly gray, a creamy silver like the inside of a sea shell. A solitary cormorant flew past them, very close, the color of iron in the fog. Time passed. She felt warmer. The day was utterly without color or warmth, but she began to feel comfortable. She felt oddly illuminated, transilluminated, as though the sun had found a place within her on this journey, yet even as she felt this, the sun turned into something else, quite simple, the knowledge that she could never again be what she had been once.

Seven hours pass as seven years. The number seven, “the number of perfection, of completeness,” sparkles across this tale, vibrating with significance. The novel pushes into the realm of the animal, of the mythological, to a landscape that feels ominous and otherworldly even if issues of the Atlantic are somehow also delivered there. At first the house reminds Pearl of a “seasonal hotel”; there’s a library where cocktails are served, tennis courts, and a sauna. There’s a generally inbred vibe, and that bloody reek of inheritance.

This novel plucks at the ragged stitch across the never-healed wound of childhood.

Old money lives on uncannily here, as it does throughout New England; Grandfather Aaron’s fortune came from trapping and skinning animals. But there is also a feral band of children; a sister-in-law, Miriam, who like a weaver of myth quilts scraps from strangers’ ruined lives into patchwork skirts; a grinningly onanistic brother-in-law, Lincoln, who eats chocolate by the fistful and whacks off in the sauna; Walker’s sister, Shelly, a fleshy balloon of a woman, taut and empty; and Thomas, the terrible wizard whose wand is “education.” If you think your in-laws are difficult, these people will make your next Thanksgiving feel like a pleasure cruise.

Thomas, not Walker, is the reason Pearl fled the island to that Florida bar. Thomas is “a man of the world.” The children are his prisoners, hostage to his ambitions for them: “He would hold the twins and talk to them in French, in Latin. He would talk to them about Utrillo, about knights, about compasses.” The twins are four months old. Thomas shows no mercy. He stuffs these kids with facts, like those poor ducklings slated to become foie gras. He collects children for this purpose. Adoptees, orphans, several biologicals. “A dozen children, more or less,” according to Walker’s somewhat alarmingly nonchalant tally.

Thomas treats the children as a topiary artist treats foliage, bending their wild spirits into stilted shapes. He gives them “social graces and intellectual hungers.” He ruins babies’ minds, Pearl fear-fully determines. He is an adult. An adult is something that says, “It does not stand to reason,” dismissing most of creation from view.

This novel plucks at the ragged stitch across the never-healed wound of childhood. “Pearl was never sure whether she should count herself among the children or the adults,” we are told early on. By the novel’s conclusion, it’s clear into whose soft, dark pupil she’s been drawn.

In The Changeling, as in much of Williams’s fiction, birth and death twine helically through the DNA of her sentences. In one feverish passage, we watch Pearl split in two: she becomes a mother. “She was having a baby in a large, freshly cut field. There was blood on the grass but it may not have been her own . . . Her thighs were spread. Her arms were spread. She was going to have a baby.”

Later, in a scene of echoing horror and grim hilarity, Pearl is torn from her airplane seat and flung into the night. The body of the plane tears down the middle. “Perhaps this really was the way the dying did it,” Pearl muses, belly-up in the sky. “One simply spread one’s arms and flew home.” The swamp into which the plane falls feels at once real and unreal, “the aurora of grasses that was the Everglades”; Pearl stumbles through the smoking yellow straits where the dead meet the living.

A corollary burden: we have to go on remembering the dead, or they will die again.

Pearl doesn’t die, but her first life is over. Widowed by the plane crash, she returns to the island with a baby in tow, a baby who does not belong to her. (To readers who are understandably concerned that I am spoiling the plot for you, please don’t worry; this book is plotting for some-thing else entirely.) Her true child, she suspects, has been replaced by a changeling. This new child is an open secret, hidden in skin. Like Melville’s unnamed sailor who we call Ishmael, the one thing we do know about him? He is Not Sam.

Nevertheless, Pearl continues to mother him. She is absorbed into the world of the island children. “Children were like drunkards really, determined to talk at great length and with great incoherence. Pearl more or less understood them in that regard.” (Here and throughout, Williams’s precise and uninflected observations stab out of the darkness, surprising the reader into laughter. At the book’s most horrifying moments, I often found myself giggling hysterically, my body turning on its ventilator fans. I loved best, for some reason, this Beckettian dead pan: “It had taken Sam almost seven years to become al-most seven.”)

Suffer the little children. You wonder how the Lord managed this before the invention of gin. Innocence and goodness are not the same thing; The Changeling shares William Blake’s respect for the wayward freedom of the children’s imagination. Williams cheerfully shreds the culture’s postlapsarian fantasies of childhood. These kids are spooky, and often annoying. Sometimes Pearl reads like Gulliver netted by the Lilliputians, tossing in a troubled sleep on the poolside chaise. She is manacled in warm, chubby fists; her own name becomes a torture device: “Pearl! Pearl! Puuuuurl!” The children speak in a sort of wise and frightening pidgin. They are impervious to the despotic logic of the adults. Pearl loves the children, but she craves silence like oxygen.

“Children should be throwing Frisbees or something,” Pearl grumbles when they cajole her into participating in their macabre play. “Children were quite disturbing really. They were all fickle little nihilists and one was forever being forced to protect oneself from their murderousness.”

If Pearl is an irresponsible mother—and that seems beyond dispute—her abdication of duty made a terrible sense to me, given her keen understanding of the obligation. The maintenance of her own life is no longer option-al; somebody depends on her. She voices a fear to which new mothers, and humans generally, are usually afraid to admit: “She did not want to be responsible for maintaining the light in herself.”

A corollary burden: we have to go on remembering the dead, or they will die again. “Memory is the resurrection.”

I first met Joy Williams in the summer of 2010, at a rolling bar cart that the kindly organizers of a literary conference had arranged to appear each night at dusk like a hummingbird feeder. If you’ve read Williams’s sentences, which streak across the mind with the fiery, otherworldly authority of comets, it might shock you to learn they have a human origin. She was and is my favorite author, a lame epithet for someone whose fiction has caused my bones to blossom. Peripherally, I confirmed that Williams herself was right beside me. Nouns startled from my head. I’d gotten “gin” off, but now I couldn’t think of a single mixer.

“Just gin?” asked the bartender, astonished.

“Yes.”

I drank a tall glass of straight gin with lemon. I introduced myself to Joy Williams. I wish I could tell you what we talked about, but the gin swallowed that up; I have a vague memory of telling some ill-advised anecdote while gesturing like a Muppet. The following evening, Joy Williams reintroduced herself to me, as if we’d never met. This was a mercy, I felt; like all mercy, as Williams’s work finds a spectacular variety of ways to remind us, undeserved.

Pearl is a guilty drunk and her drink of choice, too, is gin. You could read this thirst as alcoholism, a retreat into the padded room of a boozy numbness. My own reading, not incompatible with the alcoholic diagnosis, is that all those cocktails are a spell of protection. The gin is an icy fortress around Pearl’s vibrant interior life, her dreams and her intuitions, apple-red knowledges, a “music both intelligible and untranslatable.”

How to say anything about The Changeling without blaspheming its deep mystery, its reverence for the unspeakable, animal heart of creation?

As a child, I remember sometimes faking sick to give myself an alibi for the wilder turnings of my mind. Retreating behind the wall of a fever, I was able to conceal a budding green world from adult mockery and disgust, adult incomprehension. Gin, it seems, does something similar for Pearl. Pearl’s drunkenness provides the substrate for the novel’s magic, its icy transformation of the ordinary. Her sozzled mind becomes a kind of floating dock inside the book, anchored by her guilt.

Drinking is also how Pearl protects herself from the tyrannical interrogation of Thomas, an empiricist with a visible cruel streak (it runs from armpit to hip, according to the children). Like his apostolic namesake, Thomas believes unquestioningly in the evidence of his senses. Whereas Pearl is woozily aware that eyeblink to eyeblink, her reality is an illusion; like Job, she sees the flaw in sight itself: “The senses are such bad witnesses. She could trust none of them.” At her most intoxicated, Pearl accesses the most unbearable truths: “Everything was an artifice. What the mind thought and the tongue spoke and the heart felt.”

Late in the novel, Thomas accuses Pearl of becoming the children’s “holy fool.” Drunkenness, like madness, protects the messengers of heretical truth from disbelief, disdain, and retaliation. If you’re a drunk, nobody has to take you seriously; if you’re a drunk, there is always the possibility that you might sober up and “be reasonable.” Fiction does a similar trick. Inside the bathysphere of the novel, readers make contact with a darkness that our frightened minds might otherwise reject.

Somewhat paradoxically, Pearl’s nonstop drinking grounds The Changeling. It yokes us to a chronology we recognize, a cycle of action and consequence: ice cubes melting in glasses, a mind spreading and folding its wings, intoxicated nights and hungover mornings. It disarms us, too. We readers are more receptive to certain sobering truths, I think, because Pearl is drunk.

“Pearl had always suspected that the entire universe was made by something more than human for something less than human anyway.”

Damn. That would make anybody thirsty.

How to say anything about The Changeling without blaspheming its deep mystery, its reverence for the unspeakable, animal heart of creation? The tools of ordinary criticism seem ill-matched to the light that floods from these pages. Also, the darkness.

I read this novel when my son was four and five and six months old. I read it that slowly, with long breaths between paragraphs. It was a deeply quiet season for me, a time of humming quiet. I felt awed and cowed inside my body. We went on long walks together, the baby and I, bundled into one coat. Dogs loped up to us through heavy snowfall, sniffing and licking at my son; they recognized that he was like them, an animal living with humans. I received well-meaning emails from the hospital: Do the Diapers Ever End? Common Pelvic Floor Problems. The Most Important Person to Your Baby: YOU!

Uh-oh, I thought. There seemed to be no language for the space that had opened inside me during the birth of my son. But then I read The Changeling.

It was a cold and feverish time, February light in Portland, when it seemed that I was nursing around the clock, a clock that spun at deranging speeds, doubling my son’s size in three months, yet sometimes slowing nearly to a standstill, until I could hear each blue stalagmite dripping inside the cave of the present moment. 5:02am. 5:03am. I felt possessed by a wild joy. I felt afraid almost all of the time. And I was having dreams.

I never spoke about these dreams with any kind of specificity, aware that a midnight vision described in hospital lighting immediately becomes a symptom.

I was afraid the doctors would try to dampen my new antennae with medication; I was afraid to perjure an un-utterable understanding by trying to talk about it. And you know, I still am. I felt crazy with love.

Sometimes doctors talk about this feeling as if it is a temporary insanity, “the baby blues,” from which a mother will soon recover. Walker offers this diagnosis himself, leeringly dismissing Pearl as a silly mommy, awash with hormones, mildly and minorly hysterical. “Your world is one of bodily urges and meanings. You don’t understand anything,” he says. Thomas, later in the book, assaults her with the words with which men of the world, men of reason, have long attacked female modes of understanding: “Lunatic. Bitch.” There is something very patronizing, I think, about the notion of “the baby blues.” The sublime fear that follows birth deserves more reverence than that. Like Pearl, mothers can hear the tidal roar of the “ever-moving” present.

They know that in a best-case scenario, time will take everything from them.

The mistake doctors make is to locate the depression inside the woman, instead of the world.

“Children had never seemed reasonable to Pearl. They grew up. They vanished without having died.”

“My baby. . . .Please, I had a baby. Please give me back my baby. He was in my arms.”

“I’m having a breakdown is all,” Pearl reassures herself in the hospital, after losing Walker and her true child in the smoking yellow swamp. It says something about our human predicament that insanity would be consoling at this juncture.

The mistake doctors make is to locate the depression inside the woman, instead of the world.

“Once, in the very earliest time, a human being could become an animal if he wanted to and an animal could become a human being.”

Children are children because they exist in their very earliest hour, a long predawn before time and death take root inside their consciousness. Despite being genetically spelled down to their fingernails, every cell shaped by millennia of evolution, they live so lightly in their bodies, unburdened by memories, unbridled by convention. Pearl understands growing up to be a loss that masquerades as progress, the exile that separates humans from animals: “The secret society of childhood from which banishment was the beginning of death.” Part of the pain of The Changeling is feeling the years pass. Time draws these kids osmotically through a membrane, turning them into things like us, adults captured by the brittle carapaces of our egos.

What might it mean to become less human? To become more childlike, more animal?

By the final third of The Changeling, a storm is gathering, a terrific and imminent change haunting the atmosphere of the island. It promises erasure and violent rebirth. Thomas, for all his proprietary yammering about his young wards, turns out to have fatally underestimated them. It is the children who show Pearl the way forward, not the other way around. A change inhabits them.

“Could she be like one of them?” Pearl wonders. “She hoped so. The animal was inside her too, the little animal curled around her heart, the beast of faith that knew God.”

A few months before my son was born, we went to Eagle Creek—as we do every fall in Oregon—to watch the salmon run. They couple among the wrecked galleons of former salmon, dead and decaying fish, some thinned to a purplish translucence. Silvery costumes abandoned in the shallows. This was where life had disrobed.

Each time we reach the top of the river, I’m shocked anew to see the ghostly skins moving against the frenzied, amorous pairs, the egg-laying mothers. On this trip, I stared into the pool for a long time. Slowly, embarrassingly slowly, I merged into an understanding: life was going to shuck my skin, and go striding into the future wearing the form of my son.

In the hospital, I’d remember the huge salmon flipping out of the water, their tails thrashing over the rocks. Shuddering on the narrow bed, I learned that life is as unstoppable as death. In the moment of my son’s birth, my spasming body understood this. Death would come, as resolutely and unobjectionably as anything that happens in a dream. But life would continue.

“Once,” Pearl confesses, “she had thought that she was crazy and that she might get well. She thought that she had to be herself. But there was no self. There were just the dreams she dreamed, the dreams that prepared her for waking life. . . . The children had their lives too, new forms by which the future would be accomplished.”

The Changeling, as no other book I have read, is illumined by the spark of life, the life that wears a thousand skins. Its wisdom is unparaphrasable. A transformation, as Pearl discovers, can only be experienced. “Have you been sent here to save me?” Pearl asks Sam the changeling son, appropriately terrified by the terms of such salvation. A transformation requires an extinction.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Changeling by Joy Williams. Copyright © 2018 by Karen Russell. Published with permission from Tin House, an imprint of Zando, LLC.

Karen Russell

Karen Russell is the author of four books, including Swamplandia, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She is the recipient of a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship and was named as one of the New Yorker’s 20 Under 40.