Kamila Shamsie On Intizar Hussain's Novel, Basti

Reimagining the Intimate Sweep of History

When did I first hear about Intizar Hussain’s Basti? I can’t possibly answer that. Even for someone who grew up reading English almost exclusively it was impossible not to know that Basti was one of the great novels of Pakistan. It was on my “must read” list for years but the stuttering slowness of my Urdu reading meant that it was only when the English translation arrived on my doorstep a few months ago that I actually sat down with both Urdu original and English translation side by side, and plunged in.

How strange to discover it started in the days of the Raj! I’d always thought of it as a novel about 1971. But it was that too. How was such a thing possible? How could any novel, let alone such a slim volume, carry within it the story of both Partitions—that of 1947 as well as 1971—without becoming entirely weighed down? But of course, I quickly remembered as I read on, it is the particular genius of the greatest of writers to find ways to change our concept of what a novel can do between its bindings. Such a writer is Intizar Hussain; such a novel is Basti.

Basti, a word which might refer equally to a group of houses or a sprawling metropolis, works beautifully as a title for a novel that is vast and yet concentrated on the life of an individual, Zakir, who starts as a boy in British India, is a young man in East and West Pakistan and approaches middle-age when his already truncated nation is further truncated into simply the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Summarizing the events of Zakir’s life is a difficult business—he is precisely that character which creative writing teachers warn their students against writing: he drifts through the world, existing more in thought than deed, almost entirely passive. Of course, the wise creative writing teacher would tell students that there is only one rule of writing: if it works, do it. It works.

But why does it work? This is the more difficult question to answer but it must start with the language of the text which sets the story up as both creation myth and prelude to the Fall of Man. Here is Frances Pritchett’s translation:

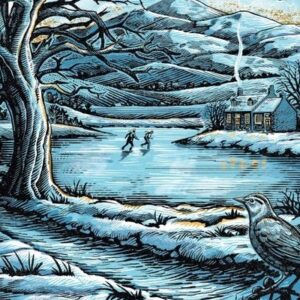

When the world was still all new, when the sky was fresh and the earth not yet soiled, when trees breathed through the centuries and ages spoke in the voices of birds, how astonished he was, looking all around, that everything was so new, and yet looked so old.

It is in no way a criticism of Pritchett to say that the translation successfully conveys tone and meaning without matching the music of Intizar Hussain’s original.

So, here we are in a prelapsarian world—this is both Zakir’s childhood, the world of innocence, and the world of unpartitioned India in which the boy runs between Bhagat-ji, who is Hindu, and his own father, who is a Muslim scholar, and collects fantastic stories from both about the world’s creation. One tells him the earth rests on the head of an elephant which stands on a tortoise. The other tells him no, the earth rests on the horn of a cow which stands on a fish. Zakir gathers up the stories, and finds no contradiction, only an expansion of his image of the world. This is all Hussain needs to do to signal to us how much will be lost later when Zakir’s family migrates to Pakistan at the time of its creation and leaves behind the multi-religious world in which he grows up. No polemic about plurality is necessary.

It isn’t, of course, a particularly rare novelist who uses story and image to convey an idea—where Hussain’s genius comes through is both in the evocative language of the stories and, later in the book, in the unexpected echo of that beginning. Here is Zakir, considering the earliest days of Pakistan’s existence:

When Pakistan was still all new, when the sky of Pakistan was fresh like the sky of Rupnagar, and the earth was not yet soiled. In those days how the caravans arrived from their long, long journeys!

Despite all that is lost to Zakir when he leaves behind his childhood home and arrives in a new nation, it is still a place of wonder, of possibility and generosity. The Fall of Man is also an arrival in a New Eden. It is only when the second Partition occurs that Paradise is truly lost.

At the time of its publication in 1979, Basti was criticised for its apolitical nature—the great events of history are far more likely to be given to us in this novel in a flowerpot knocked over by a group of protestors than in a direct comment about elections. The oppression faced by the people of East Pakistan leading up to the war is alluded to in historical metaphor rather than head-on. And yet, nothing I’ve ever read or seen in any genre better expresses lost dreams, or is a clearer call for Pakistan to hold on to the multiplicity of its traditions rather than allow a singular narrative to define what it means to be Pakistani.

By the late part of the novel, when the war has broken out, Zakir takes to writing a diary, and the entries drift between the present, history and myth—as though the only way to understand or express the moment is by reaching back to stories that carry the weight of centuries. The story of 1971 merges with the story of the Fall of Delhi in 1857 which merges with the story of Nandi the Bull on whose back the god Shiva rode which merges with the Thousand and One Nights. In the translation, a series of ellipses marks the places in which Zakir’s diary ascends into fantasy but the far bolder decision is that of Hussain’s original which runs everything together in an intoxicating, dizzying, glorious break with every tradition of the novel in Urdu, and English. A new reality called for a new form of storytelling, which also pays homage to the old forms—oral and written.

And what the old forms love most of all is a story of benighted love. If there is an anchor in this novel which so often floats free of expectation it is the story of Zakir and Sabirah, the cousin he once dreamed of marrying. On the other side of the border, in India, she is glimpsed, with longing, from the corner of his eye—and it is entirely in his hands to turn and face her directly. In any conventional story, the ending would be precisely that moment of turning—a moment in which the novelist chooses if the story is romance or tragedy. And what does Intizar Hussain do? Read Basti, and find out.

This essay was originally written for BBC Radio 3’s arts programme ‘Nightwaves’

Kamila Shamsie

Kamila Shamsie was born and grew up in Karachi, Pakistan. She is the author of eight previous novels including Burnt Shadows, shortlisted for the Orange Prize, A God in Every Stone, shortlisted for the Women’s Bailey’s Prize and the Walter Scott Prize, and Best of Friends, shortlisted for the Indie Book Awards. Her novel Home Fire won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2018. It was also longlisted for the Man Booker Prize 2017, shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award, and won the London Hellenic Prize. In 2023, her story Churail was shortlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award. Her work has been translated into over thirty languages. She is a Vice President of the Royal Society of Literature and was named a Granta Best of Young British Novelist in 2013. She lives in London and in Doha where she is Writer in Residence at Georgetown University in Qatar.