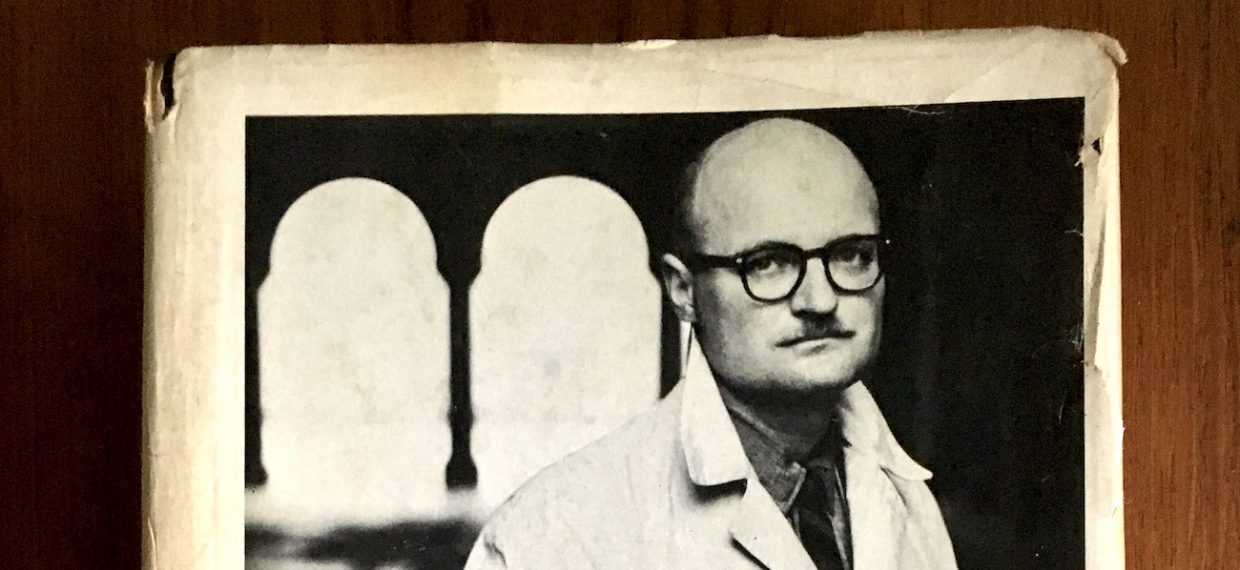

Kaleidoscopic novelist John Barth has died at 93.

It’s hard not to think about form when writing—to say nothing of starting—an obituary for John Barth. The conventions of the obituary are there to be picked up: appraise the work succinctly (see “kaleidoscopic” above), trace the biography (did you know he studied jazz?), and end with a quote, always end with a quote (“Well, I am congenitally and temperamentally a novelist.”). Hopefully we all come away with new understanding and deeper appreciation. And excellent obituaries have already been written in The New York Times, The Times’ book review, The Guardian, The Washington Post, and more, I’m sure. What more is there to say about a writer who said so much, and so well?

So I’ll keep it short: Barth was a writer of intricate and mesmerizing books. His writing investigated and excavated conventions, reflecting on literature through parody and holes punched in the fourth wall. He was concerned deeply with the novel as a form—his essay “The Literature of Exhaustion” declared “the used-upness of certain forms,” and Barth’s writing strove for a way forward while remaining aware of things “already said.” As Richard Powers said, “Barth, more than anyone, has lived to show that the novel is ever a wild goose only passing itself off as a dying swan.”

His early work in the ’60s established him as an accomplished postmodernist: the detouring The Sot-Weed Factor, the parody and allegory of Giles Goat-Boy, and the self-reflective stories of Lost in the Funhouse. His later novels didn’t attract the same acclaim, but still found devotees. Right here in Lit Hub, John Domini wrote that “John Barth Deserves a Wider Audience,” making the case that Barth’s later novels are essential experiments worthy of applause.

Barth’s work was rigorous, but always delighted in possibility and in play. There’s an evident joy in writing (did you know he wrote longhand with a fountain pen?) that is infectious. His work surprises, and I get the feeling sometimes that he surprised himself too. As Barth told the Paris Review, “I start every new project saying, ‘This one’s going to be simple, this one’s going to be simple.’ It never turns out to be. My imagination evidently delights in complexity for its own sake.”