Julian Bond Unified the Language of Black and Queer Civil Rights

On the Hard Work of Bridging the Gap Between Progressive Movements

I first met Julian Bond when he agreed to be interviewed for a book project about Martin Luther King Jr. and gay rights. My hope was to secure a comment on Bernice King’s anti-gay preaching and her claim that her father, Martin Luther King Jr., “did not take a bullet for same-sex unions.” We met for lunch in a busy restaurant near his home in the leafy northwest section of Washington, DC. He was nattily dressed, as usual, and caught the attention of several patrons, women and men, as we walked to our seats.

In preparation for our time together, I discovered that Bond, unlike other civil rights leaders like Walter Fauntroy and Fred Shuttlesworth, had argued for a number of years that gay rights were civil rights. “Of course they are,” he often said. “Civil rights are positive legal prerogatives—the right to equal treatment before the law. These rights are shared by all. There is no one in the United States who does not—or should not—share these rights.”

Indeed, there was no other African American leader from the 1960s who so closely tied the black civil rights movement to the LGBTQ+ movement. Bond conceded that the two movements were not exactly parallel: queer people do not have a history identical to slavery, and it’s people of color who mostly “carry the badge of who we are on our faces.” But Bond maintained that the thread connecting the two was discrimination based on immutable characteristics.

While his appeal to biological essentialism is now dated, it was common among social liberals of his era. “Science has demonstrated conclusively that sexual disposition is inherent in some; it’s not an option or alternate they’ve selected,” he said. “In that regard it exactly parallels race Like race, our sexuality isn’t a preference. It’s immutable, unchangeable.”

That was an unpopular position among conservative black ministers, many in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who regularly wielded biblical passages to condemn homosexuality as an immoral and sinful lifestyle choice. But Bond was insistent. “If your religion tells you that gay people shouldn’t get married in your church, that’s fine with me,” he said. “Just don’t let them get married in your church. But don’t stop them from getting married in city hall.” Marriage is a civil right granted by the government, not a religious right granted by churches, and religious believers “ought not to force their laws on people of different faiths or people of no faith at all.”

Bond also argued that his position was in line with the trajectory of King’s civil rights work. “I believe in my heart of hearts that were King alive today, he would be a supporter of gay rights,” Bond said. “He would see this as just another in a series of battles of justice and fair play against injustice and bigotry. He would make no distinction between this fight [for gay rights] and the fight he became famous for.”

Bernice King disagreed with that point, and Bond was well aware of her views. In her 1996 book, Hard Questions, Heart Answers, King had written, “Gay men aren’t real men”; they were to blame for “the present plight of our nation.” King continued to express her antigay theology when she joined Bishop Eddie Long’s ministerial staff at New Birth Missionary Baptist Church in Atlanta.

In 2004, she and the bishop—who had long depicted gay sex as unnatural—traveled to New Zealand to offer their support to a church movement seeking the defeat of a civil union bill that would have extended legal recognition and rights to gay and lesbian couples. It was during this trip when she delivered her most memorable line to date: “I know deep down in my sanctified soul that he [Martin Luther King, Jr.] did not take a bullet for same-sex unions.”

I asked Bond about that claim, suspecting he would either offer a bit of gentle criticism or simply sidestep the question. But Bond’s genteel manners, smooth voice, and sartorial splendor belied the ferocity of his reply.

“I don’t think you can call her anything except a homophobe,” he said. “You can say she’s mistaken or uneducated or not as well-versed in things as she might be, but she’s just wrong on this. And there’s one word for that—homophobe. She’s homophobic.”

He then launched into a lengthy criticism, faulting King for refusing to read, let alone learn from, her father’s papers, and for choosing instead to follow Bishop Long and his homophobic preaching. Although he spoke in a quiet and mellifluous tone, it was clear that Bond was disgusted and angered by what he depicted as Bernice’s perversion of her father’s legacy.

That’s when I realized that I wanted to study Julian Bond. When I heard him passionately condemn Bernice King’s truncated vision of her father’s inclusive ministry, when I watched him lean forward to emphasize that the black civil rights movement was expansive rather than static, when I saw his eyes light up when speaking of his own role in the LGBTQ+ movement, and when I sensed his delight that progressive movements often claimed the mantle of the civil rights movement—that’s when I told myself that I had to dig into the life and legacy of Julian Bond.

The next time I contacted Bond was in 2012, when I asked him to write the foreword to I Must Resist: The Life and Letters of Bayard Rustin. He accepted the invitation without hesitation and, true to form, penned a clear, concise, and compelling piece. “I knew Bayard Rustin; he was a commanding and charismatic figure,” he wrote. “I was taken by his platform personality, his way with words, and his ability to persuade.”

When I read those words today, they call to mind not only Rustin but also Bond himself. Like Rustin, Bond was a commanding and charismatic figure; even a cursory review of his many video interviews will reveal as much. Like Rustin, “the intellectual bank” of the civil rights movement, Bond was a personal think tank to whom various human rights advocates would turn for wisdom and strategic thinking. Like Rustin’s, Bond’s way with words, polished early on by black church and Quaker educators, was characterized by clear thinking, deliberate pacing, prophetic content, and intersectional analysis.

I returned to my idea of studying Bond’s life and legacy in the early days of the Trump presidency, while I was working on a book about nonviolent resistance in US history. Bond’s name kept popping up, especially in the period in which the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee issued its statement opposing the Vietnam War and calling for freedom fighters to engage in battle against racial injustice.

After Bond had announced his support for the controversial statement, racist members of the Georgia state legislature, with support from the state’s white media, denied him his elected seat in the house chambers. It was a very low point in US political history, and not unlike the one in which we now find ourselves—a time when antidemocratic leaders seek to crush peaceful dissenters who dream of equal justice for all.

If there’s anything that his words reveal without qualification, it’s that Julian Bond was one of the most eloquent and brilliant leaders of the resistance.Revisiting the racist attempts to squelch Bond, I thought it would be helpful to resurrect Bond’s voice for our present struggle against the racist forces of injustice. I knew I had made the right choice when I began my research of his papers at the University of Virginia. In the early days of my research, to tell the truth, I did not know a whole lot about Bond other than the basic information available in numerous civil rights books: he was the son of the famous African American educator, Horace Mann Bond; he worked in communications for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; he was denied his seat in the Georgia House of Representatives; he was nominated to be the Democratic candidate for vice president while he was still too young to serve in the office; he was elected as a state representative and senator; he lost his bid to become a US representative to John Lewis; and he served as the chair of the NAACP.

I also knew that Bond had narrated Eyes on the Prize, the award-winning documentary about the black civil rights movement and its monumental legacy. In fact, there were few things I enjoyed more as a professor than introducing my students to Bond’s moving descriptions of the movement’s nonviolent foot soldiers who overcame nightmarish obstacles between them and the “beloved community” of Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream.

What I did not know as I began my research was that Bond had carefully documented his own work in the black civil rights movement and his relentless efforts to steer the movement from protest to politics and to connect it to evolving movements for the rights of women, the poor, the elderly, prisoners of color, prisoners on death row, victims of police brutality, black Africans, and those with special needs, among others. What I didn’t know was that no one from the black civil rights movement, not even Reverend Jesse Jackson, had sought more consistently and doggedly to establish solid connections between the black civil rights movement and the many progressive movements it sometimes unpredictably inspired.

And I learned too that Bond’s numerous papers included radio commentaries, newspaper op-eds, syndicated columns, letters, notes, television interviews, oral history interviews, and other means of communication, many of them explaining in no uncertain terms his progressive positions on virtually every significant human rights issue that needed attention during his lifetime.

Bond’s works are not merely things of the past; they’re living and breathing, fresh and refreshing, and ripe for picking. If there’s anything that his words reveal without qualification, it’s that Julian Bond was one of the most eloquent and brilliant leaders of the resistance, that is, the ever-shifting group of political activists who oppose anyone and anything that undermines equal justice under law. The lasting power of Bond’s contribution lies in his ideas about strategies for resistance, ways to build what King called “the beloved community,” and to make the connections we need to make as we resist and build in the post-King years.

__________________________________

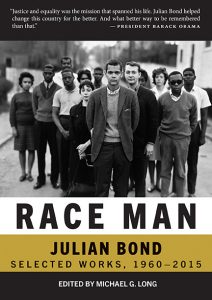

Introductory essay by Michael G. Long, adapted from Race Man: Selected Works, 1960-2015 by Julian Bond, edited by Michael G. Long. Copyright © 2020 by Michael G. Long. Reprinted with the permission of City Lights Books.