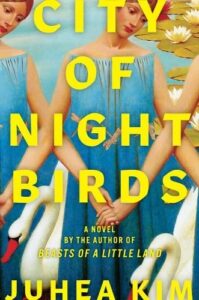

Juhea Kim on Rendering the Beauty of Ballet in Fiction

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of “City of Night Birds”

Juhea Kim’s first novel, Beasts of a Little Land, which focuses on a young courtesan named Jade in early twentieth century in Korea, during the struggle for independence from Japan and before its historic divide, was an international best seller. Kim, who was born in Incheon, Korea, raised in Portland from age nine, received a degree in art and archaeology from Princeton, and now lives in London, told NPR her intention with that first novel was to show “how we can live in a meaningful way, even when the world is falling apart, even when the sky is falling down.” City of Night Birds is a drastic pivot to the competitive life of a prima ballerina with all its struggles and glories, luxuries and deprivations.

How did she create the indelible character of Natalia Leonova? I asked. Has her own life been influenced by ballet?

I have a confession to make. The protagonist of my debut novel, Beasts of a Little Land, was as different from me as I could manage. I didn’t want to be accused of a lack of imagination. With City of Night Birds, I felt no such compunction. Natalia’s passion, intensity, diligence are all a reflection of my own personality; most of all, her reverence toward ballet and art directly mirrors my own feelings. Sadly, we are very different in terms of natural ability. I started learning ballet at age nine and danced through college. I picked it back up again during the pandemic. Lately I’ve been dancing two or three times a week at Danceworks, a studio in Mayfair, London, and other days in my living room with balletclass.com (Xander Parish-founded online program). I attend performances frequently. It’s interesting that my life has been so shaped by something I am not naturally great at. But I’m past the point of embarrassment and timidity. This is how I express myself—through words, and through movement. When I dance, I feel like a beautiful human being.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have recent years of pandemic and turmoil affected your life and your work, the writing and launch of City of Night Birds?

When I experience true art, I become obsessed with rendering it in literary form.

Juhea Kim: The isolation during the pandemic felt like a more intense form of writerly life, and I made the best use of solitude I could. On the other hand, the political, racial, and ecological turmoil posed greater spiritual difficulties for me. A critical moment came in February 2022, when Russia invaded mainland Ukraine. Like the rest of the world, I was shocked and horrified. Then of course, I had been working on a novel set in the ballet world of St. Petersburg and Moscow, and that became tenuous to say the least. The divisions that immediately appeared in the international art world were both inspiring and heartbreaking. I watched as high-profile dancers like Olga Smirnova and Xander Parish left Bolshoi and Mariinsky out of their anti-war principle. Some top Ukrainian dancers (at least one at Mariinsky who I think is one of the most beautiful prima ballerinas there) chose to stay in Russia despite criticism and suspicion. In America, there was at least one high-profile author who pulled their book from publication due to the criticism that it was set in Russia. Throughout all this, I determined that I have the deepest respect for an individual artist’s choice to not work in a certain country or boycott certain settings; they have considered this question with commitment to personal and artistic integrity.

On the other hand, I’ve always believed in making a difference through positive and cumulative action rather than abstaining or refusal. Advocacy, for me, is accomplishing something through years of active involvement. I knew I could do more for peace if I wrote this novel, and in such a way that respects the political situation while reminding us of our common humanity. Art is one of the few things in the world that transcends borders and reawakens our empathy; this may sound like a cliché, but I believe it with my whole being. Ultimately, I think I have done what I set out to do with the story itself, and with dedicating a portion of proceeds from the novel to Caritas Somalia, in recognition of the worsened food insecurity in the region following the Ukraine war.

JC: What inspired this second novel?

JK: I always start writing from a place of realization about life, about what it means to be a human. And for City of Night Birds, this realization had just been building throughout all my years of dancing, of playing the cello, of watching performances. A special impetus was seeing Angelin Preljocaj’s Le Parc, which is set to Mozart Piano Concerto no. 23. Another stroke of inspiration was the video of the singular Alexander Godunov in Bolshoi’s Carmen; I cried watching it many times. When I experience true art, I become obsessed with rendering it in literary form. And so, weaving this novel with my love for music and dance was all I wanted to be doing—aside from practicing ballet every day. Writing City of Night Birds was an act of devotion.

JC: How did Mozart Piano Concerto no. 23 shape the emotional narrative and structure of the book?

JK: My first novel was based on the idea of a symphony. City of Night Birds was inspired by the idea of this Mozart concerto, but also the concerto form in general, which showcases the entire artistic range of a solo instrumentalist. This is why you hear, for example, a presto arpeggio run followed by dramatic, sweeping legato passage. Then there are melodic motifs that are repeated or reversed throughout the movements.

When I have a piece of music before me, I both see it visually as overarching structure and hear it as prose. So I knew that as a concerto, City of Night Birds had to be in first person point of view. For that virtuosic texture, I traversed between the past and present. There are also motifs that I “heard” weaving in and out of the text. Finally, concertos are appassionato—would there be a point to listening to a cold, languid, nihilistic soloist? No. And that is reflected in City of Night Birds.

JC: What sort of research was involved in building Natasha’s childhood with her single mother, her discovery of ballet on a TV program, her early auditions at the Vaganova Academy in St. Petersburg, and the friends who come along with her during her triumphs and disappointments, as she builds a career as a prima ballerina?

JK: I read memoirs and history books, and I watched documentaries, interviews, and recordings of reference performances. There is a lot of material available online now, with ballet companies around the world and individual dancers putting up their own content. You will pick up interesting facts from so many places, but not all of it made it into the novel. You don’t have to cram everything you find into one book—it has to make sense in the world of that novel.

JC: How did you build the scenes of her rehearsals and performances, experiences at Mariinsky Ballet school and company in St. Petersburg, the Bolshoi in Moscow, her time as a star at the Paris Opéra?

JK: Being a balletomane, I didn’t even think of this as research for the book as much as just satisfying my own curiosity. All of these companies used to show their company class on World Ballet Day (unfortunately, since 2022, Mariinsky and Bolshoi have stopped participating). I have taken those online company classes many times—especially the Mariinsky ones. You actually learn a lot about a company’s style and traditions that way. But of course, seeing live performance at the respective theater is important. I took a guided tour of Opéra Garnier and saw a Forsythe performance there years ago, and of course, Paris in general is much more familiar to me. I saw Bolshoi for the first time in New York in 2014, with Svetlana Zakharova and David Hallberg as Odette and Siegfried. Then last month, after the whole novel had long gone to press, I saw Don Quixote at Bolshoi Theatre. In fact, I was also given a private tour just for me. It was so surreal to be walking around alone in the empty theatre, and I wish I had had that chance while I was drafting! I also attended a performance of La Sylphide at Mariinsky Theatre and boy, do I wish that I had had the chance beforehand. It wasn’t necessarily facts I regret—it was more the smell, the darkness of the hallways, the sensation of being in that place I didn’t get a chance to describe from experience.

JC: How common is the severe injury Natasha experienced? And her rehabilitation? I’m curious if you’ve experienced injuries from your own dancing?

JK: Without giving away spoilers, I can say that Natalia suffers from injuries that are all too common to dancers. Almost no professional dancer goes through their career without a significant injury that sidelines them for months or even years. Rehabilitation is a fact of life if you want to continue dancing. I am currently nursing a bruised toenail, and last week I woke up in the middle of the night because my big toe was gushing blood. The really strange thing is that it was fine before I fell asleep. I had even more painful injuries as an adolescent dancer—but now, as an adult, I’m better at self-monitoring and asking for help.

JC: Natasha’s attempt at a comeback at Mariinsky, now under the tutelage of Dmitri, a rival she described as “vile, dishonest, unethical,” has remarkable moments in which she is required to set aside her feelings and accept him. To what extent does the discipline of performance temper the human emotions in such a competitive field?

JK: At the risk of selling my novel short, I’ll say this: real life is more dramatic than fiction when it comes to ballet. There are so many examples, like a former prima ballerina at the Royal being barred entry to her home country’s opera house, or the acid attack on the former Bolshoi director Sergei Filin. So drama comes with the vocation; but they also find a way to work together, as when Bolshoi turned itself around after the acid attack. In fact, the culprit Dmitrichenko got out of prison and returned to company class in 2016. Is it outrageous by normal standards? Yes. But I think this happens in the ballet world because to these dancers, art is more important than anything else. There are certain codes to follow even amid the vendettas: the company class, the performance. These are sacred.

JC: How did you build the secondary themes—the love stories, the rivalries? Are there any particular ballerinas whose lives and performances gave models for how Natasha’s choices unfold?

JK: I always know the story very early on. Beasts of a Little Land “leaped” into my mind as a vision of a tiger, and City of Night Birds also “flew” to me nearly whole, with all the love stories and rivalries. What was difficult was Alexander Nikulin; I already knew what he had to do, but the plot didn’t make sense until I changed his brown hair to blond. His character and his motivations all clicked into place very quickly after that. There isn’t a real-life model for Natasha, because I have deep respect for dancers and I didn’t want to mine their personal life for my novel. However, I did watch performances by these ballerinas and their passion and artistry informed Natasha: Natalia Osipova, Viktoria Tereshkina, Ekaterina Kondaurova, Polina Semionova, Maria Alexandrovna, and Sylvie Guillem.

JC: Your sensual descriptions, from food and drink, landscapes, cityscapes, from rehearsals to parties to rare vacations are superb. Have you spent time in Paris, St. Petersburg, Moscow? How did you gather such detail?

Weaving this novel with my love for music and dance was all I wanted to be doing—aside from practicing ballet every day.

JK: Thank you for your kind words! I’ve been lucky enough to visit France many times and I truly love it. To be honest, when I take the train from London to Paris, I feel a difference immediately in Gare du Nord—the French people’s warmth, open-mindedness, and sensuality. So it was natural for me to draw upon my love of France in those scenes. On the other hand, I was apprehensive about St. Petersburg and Moscow: I had applied for and received a travel grant in January 2022, and shortly after it became impossible to visit Russia. And I am such a place-based writer; I actually think of myself as a nature writer first and foremost, because if I know the landscape, the season, and the time of day, the rest of the writing follows. So, for St. Petersburg and Moscow, I had to rely upon my own life experience and imagination as much as what I observed from Russian literature and the arts. Gogol’s “Nevsky Prospekt,” for example, might not describe the present-day Nevsky Prospekt, but I do think I absorbed some of the energy and significance on a molecular level from these texts. And when I finally visited these two cities, I realized my approach wasn’t so amiss because they were so replete with history. Everywhere I went, there were statues of poets, composers, and novelists, and these figures and their works live on in the people’s minds. But if I’d visited before writing, I probably would have changed a few things. Moscow is a lot more beautiful than I imagined, and its traffic is a lot worse.

JC: You acknowledge your connection to Russian writers and dancers, including Anna Akhmatova, Gogol, Pushkin, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Nijinsky. How have these artists’ work fed you during the writing of this novel? Your first novel, Beasts of a Little Land, won the 2024 Yasnaya Polyana Award, the largest annual literary prize in Russia awarded by the Leo Tolstoy Museum-Estate. What was the impact of that award?

JK: I feel like I’ve woven all these artists and their spirit into City of Night Birds. They are such distinctive voices across disciplines. But one thing that is in common with Russian artists is their sincere conviction in the soul—and this is something I embraced in the novel. My single biggest literary influence has always been Leo Tolstoy. To be judged as carrying on his legacy—first, artistic and second, humanitarian—by his direct descendants and literary successors, is the greatest honor I could ever have imagined. It absolutely changed my life. Because as much as I’m grateful to be a writer, it is very harrowing sometimes. Writing is sacred, but publishing is not—and it can really destroy one’s soul. But now I have something that will sustain me for decades to come.

And to be worthy of that gift, I wanted to speak about peace and the true spirit of art at the award ceremony at Bolshoi Theatre. My acceptance speech was received very well by the Russian writers, critics, and the press. The truth is that the majority of the Russian art world do not support the war—because that’s what it means to be an artist. I sincerely hope my presence and my speech added in some small way to the call for peace. And one of the more tangible impacts of the award is that I’ve donated my entire prize money to tiger and leopard conservation. It will be used to conduct tiger DNA research that will prove the need for an ecological corridor connecting Lazo Reserve with area southwest of Vladivostok—moving up this urgently needed project by two years. This will also likely expand the territory of the Amur leopard, the most endangered big cat species in the world. I’m extremely proud of that.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

JK: Unbelievably, my next book is coming out November 25, 2025, exactly a year after City of Night Birds. A Love Story from the End of the World is “an exquisite, globetrotting story collection about humans in precarious balance with the natural world” according to the copy. So I’m editing that manuscript; I’m also working on paintings and installation art inspired by the collection, with an eye toward an exhibition perhaps in 2026. I conceive A Love Story as a multimedia art project, so that’s been incredibly energizing and motivating. I’m currently reviewing the Korean translation of City of Night Birds, which will come out in 2025. I also spend a lot of time on my causes of conservation, aid and education in Africa, and animal rights—around 50 percent of my work hours. The more I get involved, the more I see a path forward, which is very exciting. Then I have to eventually get back to drafting my third novel and fourth book, which is in my head already—I just need some time away from promoting and editing other books. All of this means a lot of balls in the air, but I think late thirties is a great time to push oneself. I worked desperately hard in my twenties and early thirties, just hoping for a single opportunity to spread my wings. I have been waiting for this phase of my life, and I hope to make the most of it.

__________________________________

City of Night Birds by Juhea Kim is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.