Journeying in the Other Direction: On Bringing a Great Tamil Writer to English Readers

On Translating Jeyamohan’s “Stories of the True”

I was introduced to Aram (Stories of the True) in early 2013. I remember reading the book in a frenzy, as if the heightened state in which Jeyamohan had written it had somehow transmitted itself to me. Story after story moved me deeply, leaving me troubled for days. I was particularly struck by the author’s intimate understanding of human nature and the detail with which he had brought to life the inner world of human beings.

Aram was my gateway to Jeyamohan’s works. As I read more and more of his writing, I found myself recommending them to those around me. If the literary reader is a minority in the Indian milieu, the bilingual literary reader is a rare species. Readers from Indian languages take to reading English works, but those who begin with English literature rarely make the journey in the other direction. Why couldn’t I share the stories I loved with those around me who could not read Tamil? By then, it was nearly three decades since Jeyamohan’s debut as a writer. How was it that a master writer’s work had not crossed linguistic boundaries? How could it have been ignored for so long? Though I began to translate the first story on a whim, really, I see now that it was a culmination of both a desire to share and an act of protest.

Debuting as a novelist in 1987, Jeyamohan has written over 20 novels (including a 26,000-page epic novel, a reimagination of the Mahabharatha), more than 300 short stories, writer biographies, travelogues, books on literature, criticism, philosophy, heritage, self-discovery and much more. With such a wide-ranging body of work, his writing resists categorization. Though emerging after some of Tamil’s greatest modernist writers—Sundara Ramaswamy, whom Jeyamohan calls his mentor, and Ashokamitran, a revered predecessor—his writing marked a great departure from them in style and sensibility. His works dig deep into India’s philosophical and literary traditions to produce highly expressive narratives that privilege emotion and meaning. He often seems like a timeless voyager, bringing us grand tales from the past, present and future—a pauranika or bard, as he calls himself. As a reader, I see his writing as a dialogue with the questful, contemporary mind that is weary of cultural isolation and cynicism.

He often seems like a timeless voyager, bringing us grand tales from the past, present and future—a pauranika or bard, as he calls himself.

As a translator, it also seems to me that Jeyamohan’s prolificacy is as evident in each individual work of his as it is in his oeuvre. He is a writer who sees an epic in a novel, and a novel in a short story. Some stories in this collection are nearly as long as novellas. This meant that I needed to make the language journey through the various changes of pace within the length of these stories—the leaps of imagination, the stillness of introspection, the vigour of dramatic moments and so on—seamlessly.

Jeyamohan is a culturally rooted writer, a quality that adds great heft to his writing. Dialect is an integral part of these narratives, no doubt; the change of caste and place, for instance, is instantly understood in the original through a change of dialect. But dialect is more than an identity marker, it is an internal language that communicates the characteristics of its speaker, too. This then, became my compass, as I attempted to carry over the nuances of local registers into English.

The more I translated the more I was drawn into the text, and whole new dimensions opened up to me. It was fascinating to see how the aesthetic essence, or rasa, shifted from story to story. Poomedai’s calling as an eccentric activist imbues the ‘Nutcase,’ with humour (hasyam). The searing response of Aachi in ‘Aram – The Song of Righteousness’ infuses the story with expressive anger (raudram). There’s wonder (adbhuta) while beholding the idea of One World. Preserving this changing aesthetic in translation was at once a demanding and thrilling exercise.

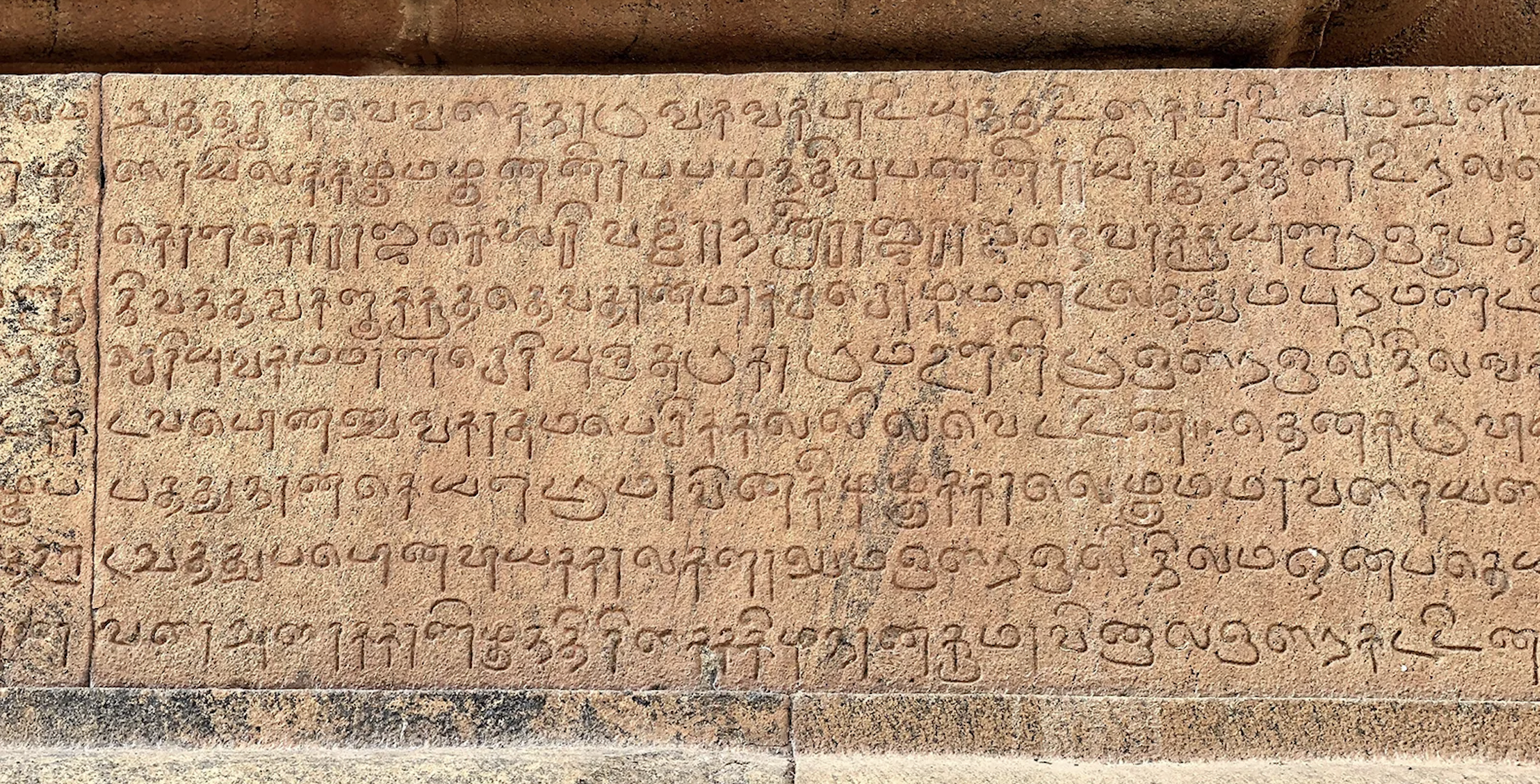

At the end of the exercise, though, I still had to deal with the elephant in the room. The single word title of the book in Tamil: Aram. A complex and, I dare say, untranslatable word. Aram is also the name of the first book of the three-part classical Tamil masterpiece Thirukkural, perhaps the most widely translated ancient Tamil text. In the English translations of the Thirukkural, ‘aram’ has commonly been rendered as ‘virtue’ or ‘ethics.’ While ethics probably comes closest in meaning, aram seems to me a far more capacious word.

I also toyed with dharma, the Sanskrit word which is a near-perfect equivalent of aram. It finds a place in English dictionaries. It is a word that most readers will be familiar with. What’s more, dharmam is a word used in Tamil too, as you will see in the stories. But in general, I had resisted substituting Tamil words with Hindi or Sanskrit equivalents, even if they were more common or better understood (such as dhoti for vaetti, paan for betel wrap). It wasn’t just the stubbornness of someone from the south of the peninsula, but I felt that to be using terms from a different part of the country would muddle the ‘place’ the stories are set in.

So, I let myself be guided by the dimensions of aram that the narratives speak of. Undeniably, there are evocations of podhu-aram or sadharana dharma, a relatively universal code of ethics that is necessary to live in harmony with other human beings, with society, with nature. Poomedai (‘Nutcase’), for instance, embodies truth; Kethel Sahib (‘The Meal Tally’), compassion; Garry Davis (‘One World’), non-violence. However, these stories reach far beyond the understanding of ethics as dichromatic, immutable codes of conduct and delve into more complex internal dilemmas.

It is in this quest that the narratives move from podhu-aram, a collective dharma, to thannaram or swadharma, the dharma of an individual. Thannaram varies from person to person for it is a journey of self-discovery—a journey to realize that which you are. Through these stories, we meet Dr K, the elephant doctor, who seems to echo Seneca’s view that the wage of a good deed is to have done it. We meet Howard Somervell who forsakes a comfortable life in England for a life of service in India. We meet a professor who so embodies the dharma of a teacher, it plunges him in eternal grief. These personalities have already reached the other shore, so to say, of swadharma when we meet them. What we witness in the stories, therefore, is a steadfast adherence to ‘their truth’.

Interweaving these stories are characters who are still on this journey of self-discovery. The boy who grapples with his adoptive faith with unyielding honesty, even though he hero-worships the man who converted him. The writer who contemplates his role as an artist in a seemingly dark world. The bureaucrat who struggles to find a way to do right by his tribal mother, and many more. These ‘moments of truth’ also stand illuminated within the frame of these stories. Thus, the stories hold in tension a truth realized, and a truth to be discovered. And so, Aram became Stories of the True. Dharma is nothing but the truth. ‘Yo vai sah dharmah satyam vai tat.’ That is what the Upanishads say too.

The reason I chose to translate this work is also the reason I am greatly drawn to Jeyamohan’s writing. No matter how dark the subject might be, his works evince a deep faith in humanity. It is not merely a disposition but a fundamental spiritual realization emanating from the author’s personal journey. In his afterword to the Tamil original, Jeyamohan writes: “By the time I turned twenty-four, I had already suffered the harshest of sorrows that a human being can be faced with. Death, ignominy, loss of my home, my land, my people and endless wandering. I was literally on the streets, begging, and I had reached the very nadir, health-wise. One of those days, I set out to kill myself. I headed towards a railway track somewhere between Kasaragod and Kumbla. I have written many a time about that morning – one that presented itself to me as an immaculate, new dawn. That it could well be the last daybreak I was witnessing made me see it that way perhaps. In the golden light of that morning, I set eyes on a worm resting on a leaf, with a body that glowed as if it was made of light. With a soul made of light. Here is a being for which every moment of this life is of utmost significance. Death may be right beside it, still, it has its own creative purpose in this world, a purpose that can be fulfilled by no other. It was a darisanam, a vision – the revelation of a world view that I later transformed into my life’s philosophy through deep and sustained reading. On that day, I resolved that there would be no more sadness in my life. That there would be no more bitterness, no more resentment. That I would not waste another moment heartbroken and hopeless. That there would be nothing secretive about my life. That that which I am would always be in plain sight, unhidden. Indeed, I have kept to the resolve ever since. No one would have seen me discouraged or weary or even physically tired from that day on. Not even Arunmozhi, who has lived with me for twenty years now.” To me, Aram epitomizes this cornerstone of Jeyamohan’s thought and attitude.

The reason I chose to translate this work is also the reason I am greatly drawn to Jeyamohan’s writing. No matter how dark the subject might be, his works evince a deep faith in humanity.

It is the same attitude that has also shaped Jeyamohan into a “literary activist.” Going beyond writing, he works with missionary zeal to cultivate a superior reading culture and an appreciation of literary heritage among the Tamil reading public. Organisations parented by his vision host serious literary gatherings, confer prestigious awards, build encyclopaedic information on Tamil literature, art and culture, and impart literary, cultural and philosophical education to hundreds of curious minds. In this sense, he is an idealist who has inspired two generations of readers and writers, one whose personality would fit right in with the pantheon of dreamers in Stories of the True.

In Tamil, Aram drew many readers on the fringes into literature. Nearly fifteen years after its publication, I still see at least one new reader writing about it to the author every other week. I fervently hope that I have captured at least some of its magic in this translation. At the risk of invoking a cliché, translating Aram has truly been a labour of love.

_________________________

Adapted from the Translator’s Note that featured in the India edition of Stories of the True, published by Juggernaut Books. Jeyamohan’s Stories of the True, translated by Priyamvada Ramkumar, is available now from FSG Originals.

You can read an excerpt from Stories of the True here on Lit Hub.

Priyamvada Ramkumar

Priyamvada Ramkumar is a translator from Tamil to English. She was selected to participate in the South Asia Speaks Fellowship Programme, where she worked with the noted Bengali translator Arunava Sinha. Her debut translation was Jeyamohan’s Stories of the True, originally published in English in India by Juggernaut Books. She has been awarded a 2022 ALTA Emerging Translator’s Mentorship as well as a 2023 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant for her work on Jeyamohan’s White Elephant. She lives in Chennai, India.