Joshua Ferris Urges Writers Not to Cower on the Page

The Author of A Calling for Charlie Barnes Takes the Lit Hub Questionnaire

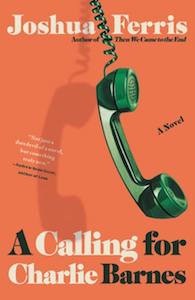

Joshua Ferris’s novel A Calling for Charlie Barnes is out now, so we spoke with him about writing habits, Sesame Street, and the books he rereads with enthusiasm.

*

Literary Hub: Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

Joshua Ferris: Everyone! I mean, my god. Why not? But not everyone will. So what I’d like, what the raw material demanded and what the finished book now requires, is the patient, forgiving, supple reader with a gently comic outlook and an appetite for play who will appreciate the arc of the whole, with its pointed reversals leading toward an unsparing realism and a structure that mimics a life in full.

Must we despair of the possibility of genuine change in our loved ones, in ourselves? Or is the ongoing hope in that possibility enough to sustain our illusions and nurture our souls? For the faithful reader, the answers are here.

But here is a little secret I’d never share with my publisher: I never cared about A Calling for Charlie Barnes as a book to be read, only as a book that had to be written.

LH: What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

JF: Ex-girlfriends. Skirmishes with the law.

LH: What time of day do you write?

JF: I write in the morning, before the day ruins me. I would spend all day in the morning if I could.

LH: Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

JF: Here is Emerson, in his essay “Experience,” at the start of a passage that eventually concludes with alarming and plaintive force:

Once I took such delight in Montaigne, that I thought I should not need any other book; before that, in Shakespeare; then in Plutarch; then in Plotinus; at one time in Bacon; afterwards in Goethe; even in Bettine; but now I turn the pages of either of them languidly, whilst I still cherish their genius.

I hate that it is a feature of the world that even Shakespeare and Montaigne will have their pages turned languidly, but that same sad fact can also unearth our oldest enthusiasms, as when we blurt out, “What? You haven’t read ______ yet?! Oh, god, you are so lucky.”

The pages I languidly turn with the most enthusiasm belong to Woolf and Wharton, Nabokov and Nietzsche, Didion and DeLillo, and to Emerson himself.

LH: Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

JF: I suspect that I was informed aesthetically and ethically by Sesame Street more than any other single thing.

LH: What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

JF: Be bold on the page. Don’t cower. Don’t conform to society when you sit down at the desk. Tear it down. Question everything. Enact subversion. Enact indecency, outrage, unsavory desire.

LH: What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

JF: Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, by William Steig. Because my father read it to me, and read it again, and read it a third time with love.

_______________________________________________________

Joshua Ferris’ A Calling for Charlie Barnes is available now via Little, Brown.