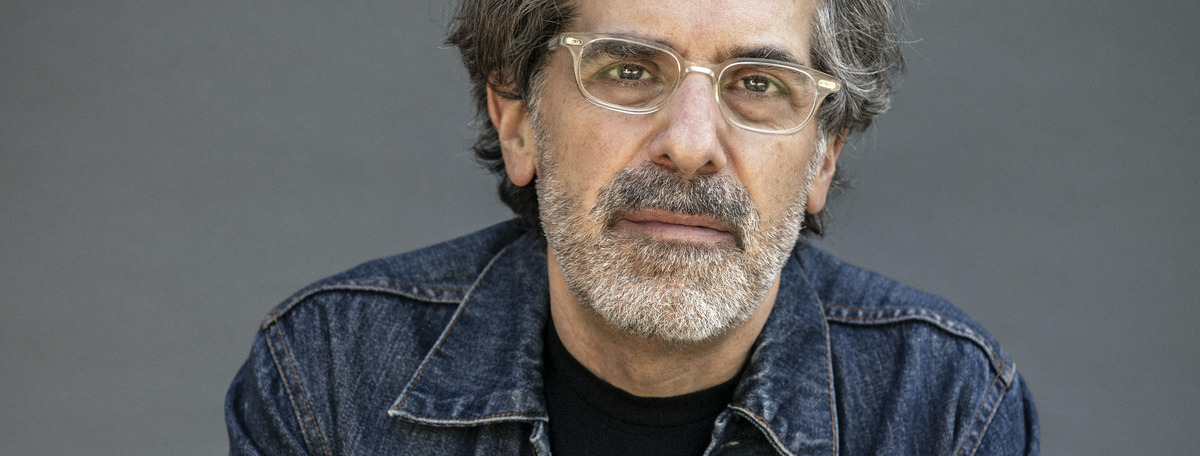

Jonathan Lethem on Revisiting Old Short Stories While Writing New Ones

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of "A Different Kind of Tension"

Jonathan Lethem appears steadily in the contemporary literary livestream, He’s earned the title “bard of Brooklyn” for fiction about his native borough. He’s invented eccentric narrative voices like Lionel Essrog, the detective with Tourette syndrome in Motherless Brooklyn, which won the 1999 National Book Critics Circle award and the 2000 Golden Dagger Award for crime fiction; Chase Insteadman, the onetime child star and his buddy underground cultural critic Perkus Tooth, wandering stoned through an alternate reality on the Upper East Side in Chronic City (2009), and the chorus of Brooklynites past and present who cobble together a manic mosaic in his metafictional masterpiece, Brooklyn Crime Novel (2023). In thirteen novels so far, he layers and twists genres, embeds homages to his favorite authors, filmmakers and visual artists. His five collections and dozens of uncollected short stories also show a virtuoso at work and play.

Now he’s pulled together stories from five precious collections, uncollected pieces from decades past, plus seven stories written in recent years. What possessed you to create a “career box set”? I asked him in our California-based email exchange in early September.

“A ‘Collected Stories’ is something you might get when you’re dead, if you’re lucky, although how you can be lucky and dead at the same time is a conundrum,” he explained. “I’m lucky and alive, so I got a ‘New and Selected.’

“So, I turned sixty,” he added. “Or I was soon turning sixty. I had enough stories to begin to think about a next collection (depending on how you count it would have been my fourth, or my sixth). A next, but I could also wonder if it would be my last—my previous collections had come at intervals of ten years, or so. And you’re obligated at a certain point to wonder if things might be last things. I felt proud that I’d stuck with the practice for so long. No one had ever asked me to stop writing short stories. At the same time, no one had ever told me it was an especially good idea to keep writing so many, once I was publishing novels. Collections are famously hard to publish, but when I suggested a New and Selected, no one told me no. I set out to work.

“I studied versions of the ‘New and Selected’ by living writers I admired. Ann Beattie’s, Charles Baxter’s, Stephen Millhauser’s. These offered a certain guidance, though to me almost any writer’s trajectory looks more orderly than my own. I began to look to a second model, the box set (perhaps by some band that hadn’t been, you know, the Beatles or Stones, but had stuck around, gotten some tunes stuck in people’s heads). I liked what this did for my thinking about the book. I recalled some interesting b-sides—stories left off the ‘albums’—and began to want to rescue them.

“No one would have any reason to know this, but I have a family connection to Mike Wanchic, the guitarist who has spent his career supporting John Mellencamp, on stage and in the studio. Mike is part of my extended midwestern family. I remember talking with him at a point where Mellencamp had thrown him the task of puzzling together the box set. Their record company had sent him a bunch of other box sets so he could consider the form. Mike was sitting in their home studio listening to all of these box sets and he said the one that really impressed him was the Kiss set. You never know.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did you arrive at the title?

Short stories at their best find keyholes into the problem, through which blasts light….they have to invent their own form each time, in order to exist in the first place.

Jonathan Lethem: Well, I stole it from The Buzzcocks. They’re not the Beatles or Stones (though maybe “Orgasm Addict” or “Why Can’t I Touch It” is stuck in your head). Nor Elvis Costello, nor Dylan nor Springsteen—all those customary bands and musicians from whom writers in my age cohort steal their titles. Why not some love for The Buzzcocks? It’s a title I’ve always liked because of the implication it hangs over the album. What kind of tension? Tension between whom or what? One wants to understand.

One answer is the tension between the long and short form. For a novelist, what are the short stories for? What are they trying to do that a novel can’t do? Then again, there’s a tension I’m permanently stuck inside by this point, between the publication lives I’ve led. I set out publishing stories in science fiction magazines, and poetry journals. The New Yorker published the majority of my stories after a point—bless them—but many of the recent examples are—hey, go figure—science fiction stories. Elsewhere, semi-realism, but some of the animals talk, like in Alice in Wonderland. Or some of the people have animal identities, like Super Goat Man.

JC: You seem to always have included a speculative element in your stories, a mix of the real and the surreal. Why?

JL: Thanks for this question, which goes right to the heart of another tension: the doubleness in my sense of how fiction works. Which is also to say how I think consciousness works. How reality works. (It doesn’t.)

I see the world through a Marxist lens, by birthright. And those insights have been extended and modulated for me through various others, like T.J. Clark, Frederic Jameson, David Graeber and so on. I’m not claiming I’m an effective activist or a political theorist myself, but that I understand our situation—our outward situation—through a materialist, historicizing perspective. So, one might think I should write strict materialist fiction, treating human experience with the bluntness of actuality, a fiction that restricts itself from the vicarious and surreal and mystical. Proletarian fiction.

Yet I see the world through a lens of Freud, too. Extended and modulated by means of Mari Ruti, D.W. Winnicott, a hundred others. I understand our situation—our inward situation—in terms of dreams, wishes, fantasies. Consciousness, human life, utterly in the grip of its own dreamlife, all our thinking and voicing caught in a web of surreal distortion, generated by our irrational yearning and apprehensions, our appetite for myth, our solipsism. We’re dreaming animals.

For me, the greatest human invention for abiding with and describing this doubleness—the outward situation and the inward situation, and the two in constant dialogue and crisis—is the novel. The greatest of novels often swell to mammoth size, contain an element of crazy hyperabundance, because of the effort of doing justice to both things at once. My own favorite examples would be Moby Dick, The Golden Notebook, Dhalgren, The Red and the Black, Middlemarch, The Man Without Qualities, The Unconsoled. Short stories at their best find keyholes into the problem, through which blasts light. Paul Williams, talking of Theodore Sturgeon, said that “his only method was tour de force.” I think that’s basically true of all short stories: they have to invent their own form each time, in order to exist in the first place.

JC: So much to chew on here. Which short stories/authors do you admire?

JL: My reading life, after the pivot from children’s stories (a pivot occurring precisely at Lewis Carroll) was galvanized by four story collections from my mother’s shelves: Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles and The Golden Apples of the Sun, Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery and Other Stories, and The Thurber Album. Many of the writers I located soon after—Raymond Chandler, Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Philip K. Dick, Franz Kafka, Stanislaw Lem—wrote short stories as well as novels. Though I preferred novels, I above all wanted to read every single word by any writer I fell for. My mind had at that point also been blown by an anthology, Other Dimensions, edited by Robert Silverberg, a window into midcentury U.S. science fiction. Another kid handed it off to me in fifth grade. Since the hardcover lacked a jacket, I couldn’t triangulate it—it was like an artifact from another reading world. In its pages I encountered Robert Heinlein, Alfred Bester, R.A. Lafferty and others. I’d put these people into a context eventually, at the public library on 4th and Pacific, on a spinner rack full of old SF. This also led to my discovery of J.G. Ballard—still one of my favorite story writers. And I found Borges when I was fifteen.

I encountered Donald Barthelme’s stories in bathroom copies of The New Yorker at my friend’s houses. In my early twenties I migrated, by association, from Barthelme, to Robert Coover and John Barth and Angela Carter. Meanwhile looking for more things like Borges and Kafka had led me to Julio Cortazar and Italo Calvino, two masters.

The editor of my first novel, Michael Kandel, who was Lem’s translator, surprised me by mentioning that Frank O’Connor was his favorite short story writer. That one remark redirected my reading, toward the “realist” tradition (always scare quotes, for me), the right turn at the intersection of Thurber and Jackson I hadn’t managed to take earlier, despite Greene and Maugham. O’Connor, V.S. Pritchett, John Cheever, Mavis Gallant, Beattie, David Gates and Lorrie Moore are those I’ve taken most to heart, though I’m surely forgetting others.

Millhauser! He seems to me like an American Cortazar or Calvino. Oh, and Stephen Dixon, Stephen Dixon, Stephen Dixon.

JC: You include thirty stories in all, including many not included in previous collections. How did you go about deciding which stories to include, and in what order?

JL: I first put every single story I could find—a few eluded me—into a 1,500-page PDF and tried to read them all, without prejudice. Of course, some embarrassed me within a sentence or two, and were dispatched quickly. Those didn’t even qualify as darlings, just roadkill on the highway to becoming someone else. After that came real sacrifices. But the gathering didn’t knit together as a book until I’d done two things: first, write “The Red Sun School of Thoughts” to complete the sequence. Second, kill a darling that really surprised me. There was an early story that had been pivotal, a career-definer at the time, and that some would have thought an obvious “greatest hit;” I’d taken it for granted that it should be included. I had to read it two or three times to move past this self-received wisdom. When I realized I no longer liked the story, I felt free to shove it out of the airlock. As Albert Brooks says in Modern Romance, “I’ll leave that up to me.”

Chronological order seemed the most vital thing, even if was obvious. You have the option of reading the book backwards to watch me grow youthful and sweet and inane.

JC: The earliest story, “Walking the Moons,” was written in 1990. The most recent, “The Red Sun School of Thoughts,” in 2024. How would you describe the evolution of your work in the short story form?

JL: I think at the start my model was what’s now called a short-short, things like Thurber’s “The Wood Duck,” or conceptual pieces like Borges or Bradbury or Jackson, very intent on presenting a conceptual notion, and then offering up some kind of reveal or epiphany or twist. Champagne bursts. And then again I tried for longer pieces, which often seemed to come out like first chapters for thwarted novels. Ironically, when I assembled my first story collection, The Wall of the Sky, The Wall of the Eye, in an attempt to appear non-trivial I favored including those long and sometimes ungainly first-chapter-of-thwarted-novel stories, and left behind the champagne bursts. This time around, gathering work from that period, I flipped the other way. I now think my better early stories are for the most part the briefer ones.

Only later did I locate the proportion I now think of as the true one for short fiction—at least for my own. However diverse the stories I wrote in the next two decades, those collected in Men and Cartoons and Lucky Alan, I think they all participate in that surer sense of proportion. Then again, I did keep writing the champagne bursts, and leaving them out of books—except I snuck a few into The Ecstasy of Influence, which was a non-fiction assemblage that included some fiction (in the spirit of Norman Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself).

My sense of how to write stories took one further turn, once I began writing stories for artists’ exhibition catalogues. If I hadn’t just gathered those in Cellophane Bricks two years ago, I’d likely have included a few here, since I think they’re among the best short fiction I’ve written. But a new thought influenced all the short fiction that came after: I began seeing stories as like paintings, in that their form concerned the relation of the interior to the edges. Unlike in a novel, you can always feel the presence of the frame.

JC: In Cellophone Bricks I particularly enjoyed “Stations of the Relocated Witness (Gregory Crewdson)—but then, I value Calvino, Kafka, Robert Smithson, Cheever, Lauren Berlant, Barthelme, Paula Fox, Anne Carson and Don Delillo—and the dark playfulness of “Jim Shaw Kills.” While reading this new collection I reread Philip K. Dick’s “Minority Report” (1956) and I was reminded that the writerly imagination “sees” the future before it’s invented. How have you navigated the ongoing shifts in technology (and the moral implications) over the thirty-five years you’ve been writing these stories? Have there been surprises? Which real-world thematic or technological or social/cultural shifts distinguish the later stories from your earlier work? How have online culture and video games triggered such stories as “Guy Bleeding All Over Skype” (2013), “The Crooked House” (2021), “Narrowing Valley,” (2022) and “Mugwump Four” (2023)?

JL: I had the strange fate of being in a front-row seat during the first big virtuality hype explosion in the Bay Area in the late ‘80’s and early ‘90’s. You had to be there. A moment when everyone’s first email address ended in @well.com, when zine culture and psychedelic culture gave way to the world of BoingBoing and Mondo2000 and Wired Magazine. I was even an employee, for a spell, of HotWired, a super-early social media space. I briefly ran a live “talk show” there, although I was myself so totally not on-line that I had to drive in my Toyota Celica from Oakland to the Wired offices in San Francisco, across the Bay Bridge, to host it. Once on my way to the show in a rainstorm I skidded across three lanes of traffic on the bridge, and was nearly an early casualty on the information superhighway.

Having been steeped in the skepticism of certain midcentury SF writers—the aforementioned Galaxy crew—I began twitching out sardonically oppositional stories right away. The first pieces in this book, “Walking the Moons” and “Program’s Progress”. And “How We Got in Town and Out Again,” for sure. When the later instances appear, like “Guy Bleeding All Over Skype,” “The Dreaming Jaw, The Salivating Ear” and “In Mugwump Four,” they’re built on that earlier foundation. But “In Mugwump Four” is partly self-mockery, for being the very last person to discover the squalid temptations of Instagram, long after others had declared the party long over. Similarly, the prediction of NFTs in Chronic City was a result of someone showing me how fun it was to place a winning bid on eBay. Once a late adopter, always a late adopter. My innocence may be my superpower.

Chronological order seemed the most vital thing, even if was obvious. You have the option of reading the book backwards to watch me grow youthful and sweet and inane.

JC: “The Red Sun School of Thoughts,” the newest story in this collection, seems to condense many of your themes. (“Virtuality, drugs, talking animals, lurkers at thresholds, failed sex and romance, parented and feral children, writers, ranting, being careful what you wish for…,” as you write in your author’s note.) Your opening sets it up: “When my father left my mother he moved from our home in the Rockridge neighborhood of Oakland across the bay to San Francisco, to join a commune called the Red Sun School of Thoughts. That was in 1976. I was thirteen.” It’s a coming-of-age story, a father-son story, a mother-son story, with the mother dying, the story of a commune with a mysterious founder. As he comes to know those who live in the commune—the ceramicist, the woman who played the flute, the film student, the poet, the Vietnam vet, the married woman, the married man, Leander—you illuminate the high intelligence/empathy and middle-grade innocence of your narrator. I wonder if with this story you have reached the epitome of a certain kind of storytelling?

JL: Thank you, Jane. I don’t know, of course. The piece is partly a mystery, but it means a lot to me. I can share a few things.

After The Fortress of Solitude and Dissident Gardens, both of which are fictions which took “coming-of-age” and “the missing/dying parent” as far as I thought I could, I didn’t think I’d approach these subjects so directly again. Then, early last year, I came across a thing online which spurred this story.

AI has begun burping up these nonsensical click-bait websites, bland, yet erroneous carbon copies of the type of sites that human content farms once labored over. One example—this example—is a “Great Quotes!” website. Strangely, while claiming to provide quotes from authors’ books, it’s shy of direct quotation, in avoidance of copyright violations. So the quotes are invented. None of the sentences actually appear in my books. They’re confabulations.

The other weird thing is that in writing bios of the authors the AI did some hallucinating, to spice up its pastiche of Wikipedia and other sources… for a brief period, Lethem actually lived in a California commune called the Red Sun School of Thoughts, where he was exposed to various alternative and countercultural ideas that later influenced his writing. The phrase was so specific I was sure it must be an external reference to something, but I wasn’t able to locate it. (Maybe a more talented Googler than myself will find what I couldn’t.) In fact, I never even traveled to the Bay Area until I was nineteen, and didn’t live there until I was twenty-one. I also wasn’t a member of a band called “The Mongrels.”

When I read this, an idea for a story arrived complete. It made a vehicle for material I’d left unexcavated in other fictions: my teenage experiences in communes, even if these were located in Brooklyn and Indiana, not California. I instantly felt it might be the right way to cinch a thirty-five-year book together—not a small task.

At first I thought it would be a novella, but it wasn’t, not quite. Just a long story.

JC: That hallucinatory bio is so weird.

JL: Wild, isn’t it? I suppose the web is cluttering up with stuff like this very rapidly, and we are all going to suddenly find ourselves unable to see over the top of it soon.

JC: What are you working on now/next? You indicate on you’ve been working on a novel and on directing a film, that you curated a museum exhibition, and even played bass on an album! Can you offer details? And is there more?

JL: The “Parallel Play” exhibition at the Benton Museum in Claremont started as an outgrowth of the book of art writings, Cellophane Bricks. It grew into an extraordinary experience for me, thanks to my terrific collaborators at the museum, especially co-curator Salim Moore. But an exhibition is like theater. When it closes, it’s gone.

The other stuff you mention is on the horizon. I’m slow-motion directing an essay film, one I’d been thinking about for more than twenty years before finally figuring out how to start. It has something to do with science fiction, but I don’t want to say more right now. And, during COVID lockdown, I wrote a bunch of lyrics for a band. Well, I’ve done that a few times before, but this time I ended up in the band, The Disassociation, which recorded an album last year. I play bass on some tracks. The record, Losing is a Luxury, comes out in March on the Shrimper label.

I also can say that I have two novels in progress, one relatively fast and one extremely slow, but I have worked on neither of them today, because I have written this for you instead.

JC: Thanks for your thorough and illuminating answers.

__________________________________

A Different Kind of Tension New and Selected Stories by Jonathan Lethem is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.