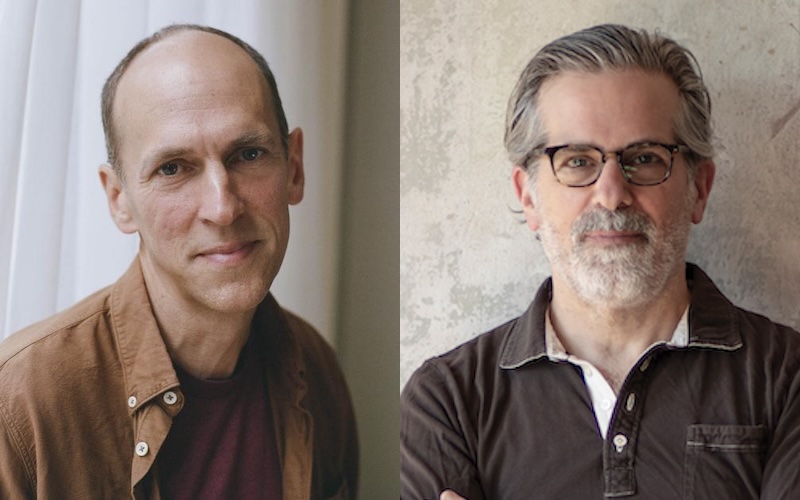

Jonathan Lethem and Ben Markovits on a Trans-Atlantic Literary Life (and More)

A Conversation With the Author of the Booker-Nominated The Rest of Our Lives

When Ben Markovits and I got on a Zoom to converse on the occasion of the US publication of his Booker-nominated The Rest of Our Lives, I kept trying to steer the conversation properly to that novel, and the fresh life it has given his books in his country of birth. That, and the unusual nature of his trans-Atlantic literary career. But it had been too long since we’d had a chance to hang out, so we inevitably drifted. We reminisced, dropped names, and commiserated. All of which is probably more interesting than the promotional boost I intended to give him. The conversation has been necessarily condensed for clarity and to take out vast numbers of further digressions.

–Jonathan Lethem

*

Jonathan Lethem: So, you and I met at the Groucho Club in London.

Ben Markovits: I remember meeting you at the Fortress of Solitude publication. Was that at the Groucho Club? I remembered you, but not the Groucho.

JL: Well, it was probably a more typical place probably for you, as a Londoner, than for me.

BM: You absolutely exaggerate my lifestyle.

Lethem: We were both Faber authors at that time. Faber did a great job with Fortress of Solitude, and I felt, for that night at the Groucho Club, London was loving me. But it also was the start of knowing you, and then, shortly after, reading you, beginning with The Syme Papers and then the novels about Byron. You first had an entire life as a historical novelist.

BM: I did, yeah. And nobody really thanked me for it. I think maybe historical novels have gone up in writerly esteem recently, but I had the sense that it was a backwater when I was doing it.

JL: It was to risk being a middlebrow writer.

BM: It was also a kind of averting of your gaze. Even though obviously the stuff that happens in the past is relevant today, it feels a little like an averting of your gaze.

JL: Yeah. Well, they’re all historical novels by the time you finish writing. But your career is uncanny. I’m very conscious of an odd thing, which is that you and I are having this conversation for an audience in the U.S., where this may serve as a kind of an introduction. I say that really cautiously because you’re a hugely accomplished writer. That goes without saying.

But you’re a famous writer in England, but you’re an American writer, and your subject is the United States. And it’s a very strange pretzel that you’ve achieved, to still be arriving here the way you are now.

BM: There’s this Douglas Adams joke that in no language is there the idiom as pretty as an airport. And I think in no language is there the idiom as famous as a writer.

JL: Yeah. It’s not real fame.

BM: So, actually, the next time we properly met, I was talking with you about Dissident Gardens. At the London Review Bookshop.

JL: My historical novel.

BM: Your historical novel. And I could tell from the audience you had a readership; you had people who had come not because of the venue, but because they wanted to hear you. And that was nice to see.

JL: That’s why we like used bookstores better than new bookstores, isn’t it? We like the kind of sticking around that books do occasionally when they meet readers. Anything can be launched into a kind of a Potemkin village existence, where you see the book jacket on all kinds of websites, and have the illusion that something is connecting. Yet if you looked at it sideways, there’d be nothing there.

You’re a famous writer in England, but you’re an American writer, and your subject is the United States.

BM: If a literary writer sells ten thousand copies, that seems like pretty good business. But in any other form of media, if you do a radio show, for example, an audience of ten thousand is a disaster, right?

JL: I often think that these misunderstandings are also where the action is. There’s the Gertrude Stein quote when she was shown into a movie studio to meet Louis B. Mayer. He says what is your secret, Ms. Stein? And she says: small audiences. Some publisher once offered me the great line that to have a bestseller is to achieve selling your book to people who won’t like it.

BM: Yes. That’s nice.

JL: But I’m willing to embarrass you in pursuit of this thought about the unusual shape of your presence. Because in England, you’re billed as a U.S.-English, or U.S.-U.K, or British American writer, whatever the right way to say that is. In the U.K. you were on Granta’s coveted list, the 20 Under 40. You won the Tate Black Prize, which is truly impressive to me. We’re all supposed to be embarrassed by prizes or feel above them or apart from them. But the Tate Black is a great prize. The list of winners is insane.

In the early years it was handed to Anthony Powell and DH Lawrence and Ivy Compton Burnett and Muriel Spark. Then recently, one of my favorite books from the UK that many many Americans may still not know, Keith Ridgeway’s A Shock. All we hear about maybe is the Booker. Anyhow, in the U.K. you’re this storied literary personage. Recognizable. If one cares about literary fame, if one believes it exists, you, you possess some in the land where you live.

BM: Go on. I’ll let you keep going. This is good stuff.

JL: It’s good to relish these moments.

But the irony is this: you’ve written a string of unbelievably insightful novels about American life. And anyone who was hearing your voice right now, as I am, you’d still pass as American. You were born in California, and I know you’re Anglo-American now, but you grew up in Texas and you write about New York City and you write about the freeways and you write about Texas and about Detroit. I need to know where that came from. You employ this seemingly effortless insight into the paradoxes and disasters of American class and race. And yet you’re sort of stuck somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

It’s a great mess to have. I think about this for myself, the way I keep stranding myself between genres and living exiled from New York City.

BM: I put it down mostly to the fact that it makes a difference to live in a country, just for publishing reasons. If you live somewhere, you know people who can help your book along . . . And I just didn’t live in America.

It’s almost embarrassing how little I’ve written about England, given that I’ve lived in London like thirty years now, longer than I’ve lived anywhere in the States. But the English are hard to write about.

Especially when I was younger, when the kids were a bit smaller, I’d make these trips to America. And because I wasn’t living there, it would have a kind of nature-documentary effect, where you saw a few years’ worth of change in one visit.

JL: Yeah, of course. There’s Joyce’s quip: a writer needs three things, silence, exile, and cunning.

BM: That’s the recipe?

JL: Of course it seems like bragging if you award yourself the cunning. That’s for someone else to do. And few of us are silent. I’m not. I don’t think Joyce was all that silent. Beckett was silent. But exile you can arrange for.

BM: So my first language, I think, was German. My mom is German and they figured that we’d learn English anyway, so they spoke German to all the kids. My dad speaks amazingly fluent and flawed German for a New Yorker who never studied it in school. But it means that now, for me, even though my German is not great, it’s still an Ur-language. So the words in German that mean something to me, really mean something to me. And I assume that’s true of New York for you.

JL: I love that analogy. I don’t have a second language, but I do think that the west and east coasts of the United States are actually two completely different realities. I know that one of the remarkable things about your writing about the United States is that you don’t make the European error of thinking it’s one place.

BM: I felt strongly when I was a kid in Texas that New York was another country, which I’d almost never been to.

JL: I used to say this to people in Toronto who’d say that Canada and the United States were so, so different. And I would grant it, yes, in one sense, but I also thought the Northeast was a region and that, as a New Yorker, if Torontonians didn’t already know that I was from New York, when I got off the plane, I could probably pass for a while. But if I took a flight from New York to Dallas and I got off the plane, I’d be spotted in ten seconds.

BM: This probably reveals more about what a jerk I was than anything else. But when I got to Yale as an undergraduate, it was my first time living on the East Coast – and a very specific East Coast environment. So I went around freshman year saying “I’m just a country boy from Texas” because I needed to distance myself from the world of, I guess . . . privately educated kids, New Yorker-reading kids. This was not the world I grew up in, even though it was an academic household. And I wanted to say, this isn’t me, even though the country boy thing was clearly nonsense.

JL: New York is still very old-world hierarchical; it still has some of what Henry James was writing about—the old school ties and the clubs. It’s closer to Europe.

Whereas California, and much of the rest of the US. is the next thing, whatever that is. The messed-up dream or plan the United States was trying to fulfill in itself. Manifest Cacophony. New York is still, you know, caught like you, in the Mid-Atlantic.

BM: I’m trying to write something over Christmas about this, and I don’t know what your experience of raising kids in California would say about it.

One of the things that’s struck me about raising kids in North London is that because English culture is so finely grained, it has this enormously sophisticated vocabulary of personality types that the kids can choose from. Whereas I felt in Texas that there was no vocabulary, which felt much freer. In North London, it’s like, you have to identify which subset you’re going to belong to.

JL: Yeah. The idea of a wide-open negotiation, of both personal identity and collective possibility, galvanizes the story that California tells about itself. That this is the real laboratory. This is the real end of the frontier.

The place remains so mysterious in a way because it’s still up for grabs. People are still feeling that they can just come here and self-reinvent. And yet it’s also a very depressing story of what happens if you disconnect. And there’s so many different forms of disconnection out here. Things sweep into the vacuum. You get cults and you get Scientology. We see the dire end of Californianism in a figure like RFK Jr. The unholy marriage of self-actualization and anti-elitist cultism.

BM: Having kids here, did they seem very Californian to you as they were growing up in ways that were foreign?

JL: My two guys both identify with the East coast through me. We go back every year and have so many friends in New York. As in a way I did when I first ran away from the east coast to Berkeley and Oakland. Playing at being a New Yorker in exile is something you can do in California – it’s one of the possible flavors of Californianism, like all those movie people who imagine they’re about to move back to New York at any instant.

I think the boys inherited a grain of this. Like we’re kind of from back there. Then when my son just now went off to college, he was in the company of a lot of Eastern kids and he suddenly was like, oh, I’m from Los Angeles. And these easterners have no notion at all what it’s like back there, where I’m from.

Of course, he’s not in the east by the standards of New York City – he’s in the Midwest. But that makes me think of your current book and about the placeless place of the freeways, which provide a deep source of understanding of what the United States is really all about. The way you see the middle of the country when you’re dipping in, moving through it, pulling off exits.

And this is why, weirdly, Lolita is a great book about the United States. Not because of the eastern college town, but when they hit the road.

BM: The road trip. Yeah, I always felt that one of the things Europeans would misunderstand about Austin is the road culture. Partly because when you drive through an American city, you just see everything from the highway and you think, Who can live in this hellhole? And then of course you take an exit and you’re suddenly in green neighborhood streets and it’s quiet and it’s a totally different scene. I guess the other part of the road trip is you go through these towns and you think, what if I just stopped and made a life for myself? Here?

JL: Yes! It’s easy to get the sense that you could live nearly anywhere, right? All these great secret cities. So long as you have that bookstore where you can buy Moby Dick for 23 cents and you can locate three people you like to hang out with. I just felt this, during an English Department gig in Omaha, Nebraska. There’s this insane and brilliant art museum and barely anyone one goes. No one knows what’s in it. And I thought: I could go and write in the cafe of the art museum.

BM: And you could have a cheaper house.

JL: That’s for sure.

I keep trying to pull us to the subject of your new book. I’m eager for people to read it. One thing I want to mention is your role as a novelist of basketball. You probably don’t know how much I identify with that.

Early in my writing life, I wrote a novella called Vanilla Dunk, an attempt to write a great story about basketball and race in a sort of a science fiction framework. The story looks kind of callow to me now, and I didn’t include it in my selected stories – but the effort still mattered to me a great deal. I researched the hell out of “basketball fiction”, which is kind of thin on the ground. Certainly compared to baseball fiction. Even to football fiction. And I came across this book by an English scholar with the strange and lovely name of Christian Messenger. His book is called Sports and the Spirit of Play in American Fiction, a survey of sports in American fiction. His big takeaway is that baseball fiction is about the American past and about a fantasy of the past, and that football fiction is about the present. It is about immediacy. It was about crisis and breaking news and the war.

But basketball fiction didn’t exist because basketball fiction represented the future. It was about a future possibility, and no one knew what to do with this future. And, rightly he says that it’s inescapably about the unconfronted subject of race.

Meanwhile you’ve stealthily become the great basketball novelist, but you’ve done it in your characteristically sidelong way. The books don’t announce themselves as sports books, first of all, except for one, I guess, The Sidekick.

And of course you have an unusual claim to basketball, since you paid your dues in the German minor leagues.

BM: It left such a deep mark on me, playing this half season of pro ball, partly because I just sucked too much. And so I wrote this book, a kind of pseudo-memoir of my time playing basketball in Germany, called Playing Days.

The point of the book was to put in words the lesson I had from the actual experience, which was a kind of reaction against the idea of the tragic flaw. I don’t know if this was a feature of your high school English classes—the tragic flaw. I hated the tragic flaw. I didn’t feel like I knew anybody with a tragic flaw.

The point of the book was to put in words the lesson I had from the actual experience, which was a kind of reaction against the idea of the tragic flaw.

It was usually hubris. That was the one tragic flaw that I remember.

JL: It turns out there’s only one in everyone. As a model, it’s all Icarus.

BM: Yeah. It’s a model for what goes wrong in human life. It seems totally inadequate.

And then I got to Germany and I thought, actually, the problem with people is that they’re just not good enough at what they do. I was playing with these guys who were in any normal sense phenoms . . . they were 6’6, 6’7, they had extraordinary hand-eye coordination, total dedication. And what this array of talents had gotten them was a shitty job in a town outside Munich in the second division of a mediocre German league. And the one person there who didn’t have anything wrong with him was Dirk Nowitzki. He was seven feet tall; his stroke was pure. He had the quickest first step on the court, he had the quickest second jump, too. There was just nothing wrong with him.

And for me, what that suggested is a kind of model for fiction, where it turns out that what goes wrong in people’s lives is not that they’re bad or flawed; it’s just they’re not quite good enough at the stuff they need to be good at.

JL: Like being married?

BM: Yeah. Like the joke you need to make when you’re having a fight with your wife that doesn’t belittle the situation. Like when you have to draw a line with your kids, even though you know that too many lines is going to mean that they ignore you. All of these things are just little technical things like keeping your elbow in when you hit a jump shot.

And if you don’t get them right, the consequences are some kind of unhappiness. Anyway, I wasn’t good enough at basketball, but that seemed like a model for writing realist fiction that would be sustaining.

JL: Terrific. And, of course, also for thinking about the life of being a writer. You were talking about Dirk Nowitzki having nothing wrong with him. But in the arts, one can run towards one’s weaknesses and explore them so lavishly that they become one’s entire art.

BM: Yes. There’s this wonderful phrase in a recent Dwight Garner review of Updike’s letters in which he talks about Updike’s self-replenishing inspiration.

JL: If you’re lucky to live long enough, one source can become a kind of fascination at your own persistence.

Maybe there’s a sports comparison here as well. When a player who is truly great–I’m thinking of Ricky Henderson, or, well, LeBron may be about to enter the same framework—refuses to retire, and persist to a point where they just play at, you know 70%, or even less, of their earlier power.

Because that’s what they do and they’re gonna do it, no matter what. But they don’t start as that, like that moment when they’re Dirk Nowitzki who has nothing wrong with them, and they’re just floating past everyone else on the court. They don’t start thinking, I would still do this if I was getting beaten to the hoop.

BM: Yeah. Do you feel like you’re writing for different reasons now?

JL: Well, I do in the sense that I feel like I’m living for different reasons. What isn’t changed? But another way that I identify with your life as a writer, Benjamin, is that you’re industrious. You just don’t stop. This is maybe viewed more favorably in England. England is the place where I identified the model for a serious writer leaving behind 30 novels, you know? Like Muriel Spark, or Grahame Greene. You just make another one and make another one and make another one. Whereas the United States, for whatever reason, there’s something suspicious about industry in writers. Like everyone should be Kafka.

Everyone should be in a battle, perhaps even a losing battle, to write just one or two masterpieces, you know? And, then the rest is silence. It’s that Beckett-Kafka modernist idea has saturated into literary culture.

BM: So The Syme Papers, I remember when it came out, my editor made a big point about the fact that it took me ten years to write, but if anybody would have published it after two years, it would’ve taken me two years to write it. It always seems slightly made up, these stories . . . it shouldn’t take ten years to write a novel unless it’s going horribly wrong, or you’re doing other things.

JL: I’m older than you are. As I round into my sixties, I sometimes think about how when I was 19 and 20, and I would go and sit alone in a room and just move my fingers minimally along the alphabet, the austerity and self-denial of that act, that was probably one of the most elderly things that a 19 or 20-year-old person could do. As opposed to going out and dancing and taking drugs. I was mimicking someone older. But now that I’m mostly entrenched in parenting and teaching and trying to keep my crumbling body and brain alive, the act of defiantly going into a room and asserting myself on the blank page is probably one of the younger things I can do. It speaks of vitality and arrogance.

BM: Yeah, I think that’s right. There’s this wonderful phrase in one of James’ letters to his brother. I think he’d gone to Europe, and after months of meaningless exchanges, he writes him a letter in which he says something like, I feel finally that real speech has passed between us.

And I feel like when you’re 19 and you go to university, you feel like you’re having a lot of real speech. But it gets harder, and I was thinking today, why does it get harder? And part of the reason I think it gets harder is because of . . . ruts.

You run out of material. Also, the stakes are higher. It’s one thing to complain about your lot in life when you’re 19 and you don’t know what it’s going to be. But when you’re 55, life is kind of what it is. You can’t talk about this stuff anymore. I think marriage-intimacy also gets in the way. You have a hierarchy of who you can talk to. And when you’re dating people, you can talk to everybody about that relationship. But then you get married and suddenly you’ve got the one person at the top. And so writing is a chance to try to get back to real speech.

JL: What’s so fascinating to me is that this might suggest to someone who hadn’t been reading you, but was only about to, as we expect everyone who reads this will be, that your work consists of a tremendous amount of kind of Hamlet-like soliloquies, or Woolfian interior monologues, where you go slapping epiphany after epiphany onto the page. But your art is very much that of indirection, Benjamin. I already used this word sidelong. Your view into your characters’ thinking is, for the reader, mostly inferential.

BM: The epiphany thing is interesting because it’s one of the dangers of modest realism that you try to spice it up with too much epiphany.

It’s like the MSG of modest realism, and I really feel like you have to watch out for it because life isn’t that epiphanic. I have this idea that the way something actually happens is more interesting than the way I can imagine it. I feel like any story shouldn’t all be meaning-flavored.

JL: Right?

BM: You should have a high-fiber content of stuff that is just stuff. I don’t know, you can get 20% of meaning in there, but if it’s higher than that, it doesn’t feel like the thing anymore.

JL: It feels like a trailer for a film instead of a film.

BM: Exactly. Yeah, that’s a nice way of putting it.

And that’s a problem of realism. I don’t think you have to face that in the same way because you’re freer to move. Does that sound right?

JL: A science fiction writer I admire very much, Charlie Jane Anders, startled me just the other day by saying on a panel where we sat together that she had chosen science fiction because it was, she thought, the most personal kind of writing. In the sense that in contemporary reality, which is all dislocation, one can’t talk about the slippages or the alienation or the difficulty of being a coherent person without use of SF’s vocabulary.

At some native level, although I was startled to hear her say that, because it sounds almost like the inside-outing of what everyone thinks that set of devices is for. But I felt recognized. My own choice in favor of surrealism or anti-realism was of that same kind, instinctively.

BM: So you’ve got this story in the new collection called “The Empty Room,” which almost feels like a realist story. But it has this conceit in it, which opens it out . . . just a little bit, into symbolism. I would say the window is less open than in your other stories.

Maybe this gets back to the meaning-flavored comment. The power of the symbol is that you don’t know what the relationship between the symbol and the rest of the story is. That if it’s too clear-cut, it loses its power.

JL: So, I mentioned all the wonderful people, including you, who won the Tate Prize. One of my most cherished British novelists might be less obvious, as opposed to how I wear my admiration of Graham Greene or Muriel Spark on my sleeve. I have in mind Anthony Powell, who makes this crazy shift at the end of this sequence of twelve novels, when his great comic antagonist Widmerpool shifts into a New Age cult in the last book. It throws the entire sequence into a mildly fantastical framework.

BM: I’m smiling. I’ve read eight of them. You’re reminding me that I should get to the next four.

JL: I revere those books. They taught me so much. Geoff Dyer told me he finds Powell suffocatingly boring, but that’s probably because he grew up in the English class system.

BM: You mentioned another writer in one of your stories that I’m a big fan of: Barbara Pym.

JL: We have this in common. I once said that I was stuck on a desert island, I’d rather be stuck there with Barbara Pym than Thomas Pynchon.

BM: Yes. She’s so good. No pettiness too small. Philip Larkin, who was obviously a friend of hers and I think played some part in revitalizing her career, wrote a wonderful essay about her. He describes this scene in which one of Pym’s women gets invited to dinner by a man who says, I bought some meat. The woman imagines the fact that she’s gonna have to cook it and she’s gonna have to clean it up afterwards and thinks, No thank you. And Larkin says, no man can read these stories and ever feel quite the same way again.

JL: Unbelievable social observer. And to me Pym is like Kafka in that when you catch that, she’s being funny. Suddenly you realize every single line is a comic masterpiece. No sentence isn’t funny.

BM: We should probably wind up, right?

JL: We’ve given more than was asked for. Like, we brought meat.

BM: We brought meat.

_____________________________

Ben Markovits’ The Rest of Our Lives is available now from Summit Books.

Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem is the bestselling author of twelve novels, including The Arrest, The Feral Detective, The Fortress of Solitude, and Motherless Brooklyn, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. He currently teaches creative writing at Pomona College in California.