Jonathan Escoffery on Navigating Identity, Blackness, and Literary Fame

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of If I Survive You

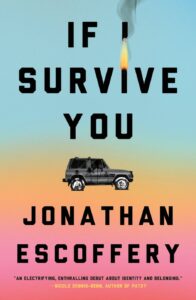

Jonathan Escoffery’s first book, the superbly crafted, kinetic linked story collection If I Survive You, arrives with four starred pre-publication reviews and an early rave from The New Yorker’s Katy Waldman, with more to come. He’s a rare debut author with a lengthy track record. His stories have won him such literary honors as the Plimpton Prize for Fiction and a National Magazine Award. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Bread Loaf, Aspen Words, Kimbilio, and is currently a Stegner fellow at Stanford.

“The various honors have helped me lean into my writerly strengths and interests, and I think that’s a good thing,” he notes. “It builds confidence when you’ve received so much support and encouragement for your writing. I think there’s a danger that you might start to buy your own hype and believe anything you write must be good because you wrote it, but the truth is always right there on the page.

The most important thing a writer can do, I think, is sharpen their sense for whether what they are attempting to accomplish on the page is likely to be received by their ideal readers as they intend, and the workshops at many of these programs I’ve attended have helped me build confidence in that skill. It also helps to know what conversations your writing is taking part in, and being as well read as you can be in your particular area of interest helps with that. I’ve gotten so many crucial reading recommendations in these programs, from professors, workshop leaders, and from members of my various cohorts.” Our conversation took place via email.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the last few tumultuous years been for you? Where have you been living, working, preparing to launch your story collection?

Jonathan Escoffery: Since leaving Miami in 2011, I’ve moved cities every two or three years. I’m not particularly dedicated to this nomadic lifestyle, but I’ve been chasing funding and various opportunities that have allowed me to center my writing. I’ve been in Oakland for about one year now, and I commute to Stanford University to attend the Stegner Fellowship’s weekly workshop. I spent the two years prior to moving here in the L.A. area, where I attended the creative writing and literature PhD program at the University of Southern California.

I probably don’t need to recap our collective turmoil, which, personally, has felt surreal, but my career began taking off in so many wonderful ways just as the COVID-19 pandemic was starting. The discord between that international tragedy and my personal success feels strange, to say the least. And then, to speak of personal tragedies, my father died this August, just weeks before my collection was set to debut, and the mix of emotions that has brought on has been the most disorienting thing of all.

I’ve had to challenge many of the assumptions I previously held when my world was limited to a handful of zip codes.

JC: How has your own life experience and travels influenced your perspective in the eight linked stories in If I Survive You?

JE: One important realization I’ve had over recent years is that I never could have written this book without having done a lot of growing as a person, and part of that growth was a result of gaining perspective as I’ve moved across the country and traveled internationally. I’ve had to challenge many of the assumptions I previously held when my world was limited to a handful of zip codes.

Drawing on my lived experience was especially crucial when making observations about how race and ethnicity are treated in Miami, versus the Upper Midwest, versus Jamaica, and there’s an ethical imperative to accurately represent these things on the page.

JC: How long did you work on these stories? Under what circumstances? Which was the first you completed? Which the most recent? Do you have a favorite?

JE: The first story that I completed that made it into the final version of the collection is “Independent Living.” I began it as an essay about my job working at a federally subsidized elderly housing community much like the one my protagonist, Trelawny, finds himself working at. A couple of these stories began as essays, but I have an inclination to turn my narrative essays into fiction because I can grow the conflict and have my characters make the more interesting mistakes that I try to avoid in real life. I overhauled the story over the course of many years and it officially became a Trelawny story when I was putting the book together and looking for ways to make the stories work as one cohesive world. I started about half of these stories during my time at the University of Minnesota or just after I graduated.

The most recent piece is the title story, which closes out the book, and which took me a year just to draft. I was living and working at the now-shuttered Wellspring House retreat in Ashfield, MA, when I wrote it, but I would take excerpts of it to different readings I participated in in Boston and at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, to see the audience response and to motivate myself to finish it.

My favorites tend to be the Trelawny stories, but then there’s “Under the Ackee Tree,” narrated by Trelawny’s father, Topper, and that story breaks my heart every time I read it.

If I count my earliest sketchings of the family in If I Survive You, then it took me ten years to write. If I count from when I really started to see the book I was trying to write, it was closer to five or six years.

JC: Trelawny is a multiracial, first-generation Caribbean American who lives in Miami. In your first story, “In Flux,” he mulls over the continual questions he has faced since he was nine and someone asked—”What are you?” and “What language is your mother speaking?” How did you go about envisioning his exploration of identity and community—especially in an international city like Miami?

JE: “In Flux” was another story that began as an essay, and I think part of what made me interested in the story was that I’d had the experience of living in Minneapolis for a few years, which gave me new perspective on how the treatment of race and immigration, and ideas about what it means to be American, can vary across regions.

Once I began to fictionalize the story, though, Trelawny became, to me, someone who just wants love and acceptance, and he’ll take it where he can find it, but he can’t seem to find that place of belonging, even as he leans into the different parts of his identity that might make him legible to the groups that ultimately exclude him. Narratively, I wanted to show how disorienting that “what are you” question can be, especially when no answer will satisfy the people asking it.

My intended reader might also be anyone who finds themselves skeptical of the boxes that society tends to hem us into.

Part of the challenge Trelawny faces is the challenge I initially faced when I set out to write this book. Who is the hero of this story? Can he be Black American and Jamaican? Can he be Black and multiracial? Is his being too complicated for readers to digest? I decided to make the problem for the author the problem my protagonist faces.

JC: Kicked out of his father’s house and living out of his car, Trelawny scours Craigslist ads and ends up serving poolside in glitter and a Speedo, kneeling on a caiman’s tail, and giving a woman named Chastity a black eye, all, motivated by the “exquisite racking compulsion to survive.” In “If He Suspected He’d Get Someone Killed This Morning, Delano Would Never Leave His Couch,” which revolves around Trelawny’s brother Delano, a Hurricane Irene warning is just the beginning. In “Pestilence,” millipedes and locusts swarm around Trelawny’s parents’ house in southeast Miami, crabs scuttle inland. There’s continual action. Did you set out to make sure things happen in these stories?

JE: I think this comes from the fact that I never wanted to write literary fiction, which is to say, literary fiction as I first imagined it, which is to say, boring, navel-gazey fiction. Thankfully, my education disabused me of this early prejudice—clearly, I write and very much love literary fiction—but I grew up admiring books with storylines that prized ingenuity, and I always believed bridging unique, sweeping stories with energetic prose was the sweet spot I wanted my work to live within. When I think about what I want to write about, I’m plucking stories from real life, perhaps my life, perhaps from a post I read on Craigslist, from which I imagine my way forward. Exciting things are happening all around us and that’s what holds my attention. I also feel compelled to preserve my own history, and in a story like “Pestilence” I wanted to make sure people understand that a place like this existed.

When I write and revise, I continually ask myself, are you enthusiastic about this? Are you boring yourself? Is your mind starting to wander? If I’m bored, there’s no reason to believe readers will feel differently. Sometimes, this is a matter of content, but sometimes it’s about the way a story is being told, and I look for ways to build in a rhythm that lulls, while also keeping readers uncomfortable in their expectations about what will happen next.

JC: In “If I Survive You,” Trelawny is “one gig away from destitute” when he answers a Craigslist ad: “Watch My Boyfriend and I,” and enters a world of sexual game-playing that offers a chance for you to describe wide range of racist behaviors. Why did you make this multilayered story your title story and the last one in your collection?

JE: I went into constructing the story with the idea that it would bring together everything that comes before and offer a sense of climax and conclusion. What I love about the story “Odd Jobs” is that the action takes place over the course of about an hour. In that earlier story, Trelawny would have been excluded because of his race—the post says “sorry, no Black guys”—but he shows up and takes part anyway, and can do so because people in Miami are, to some extent, unable to pin down his race.

When I write and revise, I continually ask myself, are you enthusiastic about this? Are you boring yourself? Is your mind starting to wander?

In the title story, I wanted to revisit Trelawny’s sense of desperation. By this point in the book, we know Trelawny to pick up these Craigslist gigs as a mode of survival and we know these jobs have a way of going sideways. I felt there was a lot more to say about the way these sketchy gigs—which I’ve seen posted online—reveal people’s attitudes about race, and I wanted to imagine my way forward from such a posting. I wanted to contrast that blatant exclusionary racism from earlier in the book with what happens when people with power decide they want you specifically because of your Blackness.

JC: Who do you envision as your audience, your intended reader?

JE: One of the reasons I wrote this book, the reason I felt compelled to finish it, is that I’d never seen a family that looks like my family in literature or on TV, and I wanted to finally see myself. So in that way, I’m my intended reader. But I think there are so many experiences that this fictional family has that readers can relate to and my hope is that through humor and through the strange adventures these characters find themselves on, any reader can connect with the book. I think it’s accessible—I’m told it’s a fast read—but I also think my ideal reader is savvy and ready to pick up on conversations that these stories move forward without necessarily rehashing from the very beginning.

My intended reader might also be anyone who finds themselves skeptical of the boxes that society tends to hem us into.

JC: What sort of research did you do for these stories? Including digging into your own memories and records—photos, journals, archives?

JE: I love books that set into narrative the finer details of the characters’ jobs, and I read articles and used YouTube to learn about some of the work my characters do in the book. I find it’s helpful to see a job being performed, rather than just reading about it, if I’m to write about it convincingly. I’ve worked some strange jobs myself, some of which made it into the book, and I have a good memory for my own minor traumas and for some of the absurdities I’ve noticed working these jobs.

I spoke with a lot of Jamaicans of my parents’ generation to gain insight into what exactly drove so many to emigrate to the U.S. in the 1970s, and I read as much as I could to verify and further contextualize these accounts. In terms of records, I scoured my own birth certificate at one point, to make sure I hadn’t imagined that the word Negroid was printed on it (it is), when a literary journal’s fact checker thought that was farfetched.

JC: What are you working on next?

JE: If I may be deliberately vague, I’m working on a novel that takes place back in Miami. But story ideas keep sneaking their way into my imagination and I’ll admit my next collection is being written in my phone’s notes app and in the back of my head.

__________________________________

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery is available from MCD/FSG, an imprint of Macmillan.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.