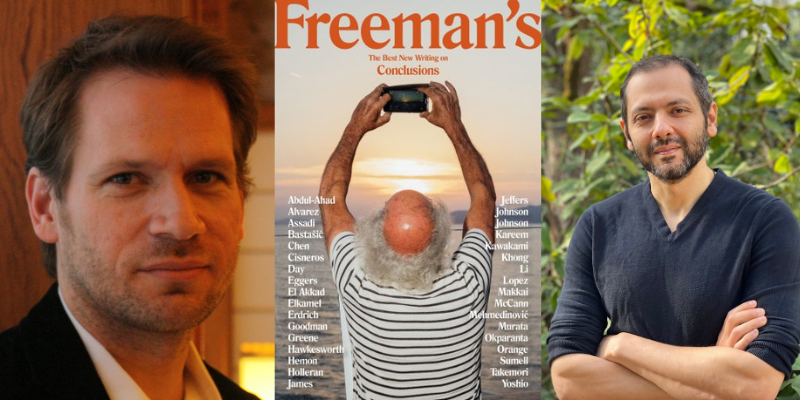

John Freeman and Omar El Akkad on a Literary Magazine’s Final Issue

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Poet, editor, and writer John Freeman and novelist Omar El Akkad join co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about the final issue of Freeman’s, a literary magazine founded in 2015. El Akkad, a contributor to the volume, describes founding editor Freeman’s intense and uniquely broad interest in literature, as well as his unusual ability to curate collections of pieces that are in conversation with one another. Freeman explains the work and support that made the magazine possible, and reflects on the moment when he decided to pursue it, as well as how he decided to conclude it. They discuss the publication as a project that created a valuable network of literary connections and gave many writers a new context and outlet for their work. El Akkad reads from “Pillory,” his story which appears in the final edition of Freeman’s, and talks about how he came to write it.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Todd Loughran.

EMBED FROM MEGAPHONE

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: I’m teaching a creative nonfiction class right now. And I tell students: think of when you’re doing a polemic, you have to define terms like… Tom Frank in his book What’s the Matter with Kansas defines this term called the “great backlash” as a way of explaining what conservatives were doing in the late ’80s. And what I love about that piece is how easily you can quickly define these terms that don’t exist in our language, but we understand how they work, and they fit really easily into the flow. But the piece wouldn’t work without you creating a terminology for what’s happening.

Omar El Akkad: Yeah, I mean, I spend a lot of my time trying to think about the price of admission, because a lot of my stories end up in a place where there is a price of admission. I wrote a story a while back called “Government Slots” about this world in which there’s something like a post office and everybody gets a little box. And whatever you put in that box is believed to follow you into the afterlife. It disappears the moment you die. And so the whole story, which has almost no plot to speak of, is about what kind of things people would take with them, if they thought it would follow them into the next life or whatever comes after. And so, some of these boxes are full of Bibles, resumes, condoms; people have very different ideas of what’s coming next.

But that was another story where we had to think about the price of admission, like, here’s what you need to know about this setup. Because once I give it to you, I’m not interested in that anymore. We’re going on the emotional aftershocks of that. But it’s something I have to think about a lot. And I do it to varying degrees of success.

WT: I mean, it’s very hard to do world-building concisely, right? I think that story does a great job—it’s not a very long story, and it creates an entire world very quickly. Can you talk to us a little bit about, as a writer, you mentioned a little bit earlier that you were aware of Freeman’s and were reading it? When did you start reading it? In your mind is there such a thing as a “Freeman story”? Are there particular things that you value about the journal? We’re trying to start… find somebody to do a long book about this later, criticizing John for somehow doing something wrong, and the people that he’s brought into the novel like they do with Iowa.

OA: I make fun of them a lot. And then immediately send them an email saying, “Please don’t drop me. I beg you.” If I’m being perfectly honest, my ignorance knows no bounds. And the first time I came across Freeman’s was when I was researching John, so, the backstory, for whatever it’s worth, is that in the middle of working on the edits to my second novel, this book called What Strange Paradise, my editor Sonny Mehta passed away. And in fact, the last trip I did before everything went to hell because of the pandemic was to his memorial service in New York. And I was in a really bad place. I sort of won the lottery, with respect to my first agent, my first publisher. You’re a first time novelist, and you have no idea what the hell you’re doing and suddenly, you’re put into this position where you’re working with people who are among the best who have ever done it.

I didn’t want to do anything else with writing as a commercial endeavor. And John comes into Knopf, and I have no idea whether he asked for me to be working with him on another novel that still doesn’t exist, that I’m still working on. I have no idea what the backstory is. And I start looking up this guy, and I’m like, “Oh, he has a magazine named after him. That’s something. I guess I better read this thing.”

I think Arrivals was the first one that I picked up. And I just became obsessed with it. It was a great introduction to the kind of person John is, which is the sort of person that you can sit with and say, “Tell me your five favorite Nepalese poets,” and he’d be like, “Just five?” And you’ll have to come up with another container, or sub-container, to put it in, because the extent to which he really cares about literature as an individual effort, but also literature into how the stories speak to one another, I think is unlike almost anyone I’ve ever worked with. And so that’s how I became acquainted with the entire endeavor.

It was weird reading somebody’s work and reading the thing they’ve created before, I think, we ever had a discussion in person. Or no, we did have a discussion in person at the Vancouver festival, when I had no idea why you wanted to talk to me at all, because I had no idea what was going on, on the other side of this. But it was part of my introduction to who John is, as a literary mind. And that is a facet that continues to astound me.

John Freeman: Vancouver is a great place. I go to these festivals, in part in order to meet people like Omar. And for the last 10 years, Vancouver Writers Fest has been generous enough to schlep me out and in exchange for me moderating an event or two, I get to mooch around and listen to people whom I don’t know read, and it’s been a wonderful education, not just in Canadian lit but in literature from around the world. And Omar’s frequently roped in to moderate events as well as be in them. And so I had seen Omar both on the end of questions and on the questioning end. And it’s very unusual to see a novelist be able to do both. You two are particularly quite odd in that regard. Because most novelists are world builders, but they’re not necessarily journalists and interrogators, and both of you have worked in some capacities as nonfiction writers yourselves.

And Omar, of course, has spent a lot of time as an overseas reporter, sometimes in conflict zones. And it’s exciting when you see someone’s mind framing stories by the questions they ask. And then you can see them do that but in the fiction way, which is to create sort of invisible structures of enchantment, which are asking questions, but are not necessarily visible.

So, you know, with American War, what would happen if everything that ever happened around the world as a result of America’s imperial flex happened within American borders? What would that feel like? And you know, similarly, in What Strange Paradise, what would happen if you reset the story of Peter Pan but on the island of Lesbos, or in the middle of the Mediterranean, with two children trying to walk to safety? But I think that there are some people who have worked as journalists and are novelists – Colson Whitehead is another – where you can see that the skills are related and enhancing each other.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: John, you’re talking a little bit about questions. And you wrote about that in your introduction to the issue and you also write at some length about the late Barry Lopez. And you write about how keenly attuned he was to living and the intensity with which he paid attention to everything. And the issue includes, incredibly, a never before published story by him, and also includes a never before published poem by the late Denis Johnson. Can you talk a little bit about including those pieces in Conclusions?

JF: Yeah, there’s also a poem by an 11th century Chinese poet translated by Wendy Chen, who came to me as a submission at Knopf, and I was just completely bowled over by these poems. Li Qingzhao, who’s sort of regarded as highly as Li Po, but has a kind of Sappho-like quality to her poems. They’re poems of longing and love. The voice feels so immediate. And those poems have been known and been around and Wendy has just done a new translation.

In the case of Barry and Denis Johnson, those pieces were found recently. I’m friends with Barry’s widow, the writer Debra Gwartney. And when I went to Barry’s memorial up in Oregon, in his study there was a poem open on a kind of pedestal facing the woods, which had been recently scorched from one of the big Oregon fires. And it was a kind of poem that was about stewardship. And I had no idea Barry had written a poem and it was dated 1980-something in Port Townsend. And I asked Debra, I said, “What is this?” And she said, “I think he wrote this as a broadside in benefit for Copper Canyon.” So I asked if, at a later date, we could publish that. And she said, “Absolutely.” Because it’s a beautiful summary of all the ways in which maybe we underestimate our footprint on the world, but also, how much more improved our lives would be if we saw stewardship as not an “also” but just as a primary function of our reason to live.

And in the course of laying that out, she wrote back to me and said, “Hey, I’ve been looking through Barry’s papers, and I found this essay, do you want to look at it?” And she gave it to me on my birthday last year in Seattle when we were having an event for Freeman’s. She has a harrowing, beautiful piece about driving out of the fire that eventually claimed a big part of their house. They survived, but that was probably the beginning of the end of Barry’s life. They lived on a salmon river, and the river was really damaged, and the salmon suffered as a result of it. And in the course of this event, she just handed me a printout of this piece. And it’s a gorgeous piece of writing of walking home along this river. And for whatever reason, maybe someone commissioned it, and he never liked it or decided not to turn it in, or maybe the magazine folded, all those things can be very likely. But it’s a perfect piece of writing and a perfectly observed walk home. And it’s at the end of the day. So it felt like the most obvious place to begin the issue.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento.

*

Freeman’s • Wind, Trees • Maps • How to Read a Novelist • Dictionary of the Undoing

“Pillory” • American War • What Strange Paradise

OTHERS:

Freeman’s Conclusions | Vancouver Writers Fest • Freeman’s Conclusions – The Nest – Vancouver – Oct 20, 2023 · Showpass • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 3, Episode 22: “The Unpopular Tale of Populism: Thomas Frank on the Real History of an American Mass Movement” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 3, Episode 17: “Poetry, Prose, and the Climate Crisis: John Freeman and Tahmima Anam on Public Space and Global Inequality” • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 1, Episode 5: “Is College Education a Right or a Privilege?” featuring John Freeman and Sarah Smarsh • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 2, Episode 17: “Emily Raboteau and Omar El Akkad Tell a Different Kind of Climate Change Story” • Denis Johnson • Barry Lopez • Wendy Chen • Li Qingzhao • Li Po • Debra Gwartney • Michael Salu • Colson Whitehead • Jon Gray