John Clellon Holmes on the Funeral of His Longtime Friend Jack Kerouac

“I hoped that no one would ever mourn me so self-centeredly.”

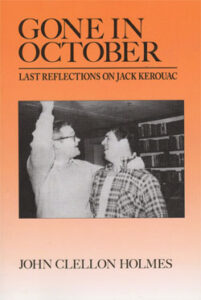

Above: John Clellon Holmes and Jack Kerouac, early-1960s. Photograph by Shirley Holmes.

Funeral homes are all alike, of course. Archambault’s was Victorian in decor, with pale green walls, lofty ceilings, an ornate balustrade going up from the vestibule to—what? The formaldehyde rooms. The butcher shops. Wherever it was they stored the coffins, and showed them to customers susceptible in their bereavement. Two “showings” were going on in opposite rooms, and the neatly lettered placards (like those in hotel lobbies telling you in which room your convention is being held) announced “Kerouac” on the left and “Levesque” on the right.

The Kerouac room was filled with people—middle-class, well-dressed Lowell people, and a few kids (Custer-bearded youths with grave, out-of-place faces, and mini-skirted girls, solemn with they knew-not-what unclear emotions). Most of the local people seemed to be Sampas relatives, and suddenly I realized how few Kerouacs there had ever been. Later, we met a row of young Kerouac second cousins—pretty little girls with that dark, round-faced Breton look, and muscular, abashed boys from Dracut or Nashua. Among the crowd was Charley, the eldest Sampas, news-editor of the Lowell Sun, a large, suave man with flesh on him, in a well-cut business suit, balding now, the successful head of the clan, his urbane eyes on all the details.

It was Charley who had encouraged Jack to write when Jack was best friends with his younger brother, Sebastian, who had been killed in Europe in 1944. Charley had told Jack that if he wanted to write he ought to get out of Lowell, and perhaps Charley, too, had wanted something more than to be standing there in his expensive suit, with certain private ambitions unachieved despite his position in the community. We met further Sampas relatives, and friends, and friends of friends, most of them Greeks in that French funeral home, and there, too, was Stella on a settee off to one side, out of the theatrical lights that bathed the coffin, and the banks of fresh flowers, and—Jack.

No need to say that no one had ever seen him that way since he was Harcourt Brace’s soulful young Thomas Wolfe 20 years before.

Down to it, I didn’t much want to “view” whatever some mortician had thought to fashion out of what was left of him, but I knew I would. Allen and Peter and Gregory went right up through the crowd to have a look, but whether they had seen the handiwork of funeral homes before I didn’t know. Allen and Peter had observed dozens of corpses on the burning ghats in India, but (as Allen said later) that was natural, you see the husk of the body for what it is—organs, so much simple meat, just the garbage of our chrysalis from which the butterfly has flown, nothing but the residue of transitory life.

But in the war, I had seen half-a-hundred dead sailors being gotten ready for shipping home to inconsolable parents and wives, and later “viewed” my father laid out under the lights like a waxwork-figure in Madame Tussaud’s that is somehow unlike the person precisely because cold skill has so striven to make it resemble them, feature to feature, and you stand in utter perplexity wondering why it doesn’t, only to become aware that what is missing is not merely movement, animation, but something else, the invisible spark that makes the mask cohere, the soul lighting up the persona from within, the unique and irreplaceable Being that invests the face with human possibilities.

Anyway, I pushed my way through the crowd alone, fearful I might be revulsed and that it would all come down on me if anything of Jack was actually there, and over the dark silhouette of a shoulder, I saw him—laid out in flowers, in the prescribed funerary attitude of tranquil slumber, hands folded with a rosary entwined, in a pale shirt, a natty bow-tie, and a sport-jacket.

No need to say that no one had ever seen him that way since he was Harcourt Brace’s soulful young Thomas Wolfe 20 years before. And the face? It had been made to look as peaceful as a babe, the brows slightly knotted but with perplex rather than pain, all the fevers gone, the mouth not his mouth at all, the color of the flesh a rather pale pink in the lights, Jack’s sweaty, grinning, changeable expression nowhere to be seen. He looked thin, calm, waxen, almost choir-boyish—and Jack had once been choir-boyish alright—but this was a faintly prissy, I’m-alright-Jack Jack, and no Jack I’d ever known. Later, Allen would say: “I stood there, and suddenly I expected him to wink. That is, the Jack that was watching all of us watching him would have made that eyelid wink to tell us that everything was all just so much vapor circling upwards in the void.”

Gregory was kneeling at one side of the coffin, crying now, and I remembered the easy, public tears of Italy, the bawling men coming back from Venice’s burial island in the dignity of a grief that is openly acknowledged, and I looked at Jack again, and felt for just a moment the sheer obscenity of death, the irreparable period that it places at the end of portions of our lives, closing us off forever from the consciousness that has gone, and the first sick feeling of gut-loss came over me. “It will be different to write from now on”: the words came back, and I hoped that no one would ever mourn me so self-centeredly. Tears welled up into my eyes, the involuntary tears that we sometimes shed for the mute flesh itself. He wouldn’t walk, he wouldn’t run, he wouldn’t ever come into my house again, yelling like a banshee, or grinning pensively, or moody with his special thoughts. That’s what I felt. His body died before my eyes, and I had to accept that I was stuck in my own body, in my own flesh, and that this mannequin was the last I’d see of a friend of 21 years of feverish association. I put an arm around Gregory, and we turned away.

Death makes you talk, you talk so as not to think, you chatter as if you’d found a similar soul at the worst cocktail party of all time.

I found Shirley, who had taken only the briefest look from a distance, and we went up to Stella, who broke down again as we bent over her, and Shirley knelt down and stayed with her for a while after I’d muttered a futile word or two, hugged her, and cursed under my breath. Cursed what? My own closed throat that wanted to bring up something consoling, something that wouldn’t push her over any further—all that grief-role crap which, like joy-role crap, is only crap, after all. Better to stumble out: Jack’s dead! What am I going to do! But instead trying for control, trying not to say a word that would trigger emotions neither of us could afford. And all the while her eyes observed me, something going on behind her tears: “Is this John Holmes? Is this Jack’s friend? Why isn’t he suffering? Is he suffering? What kind of suffering is that?”

Hours, hours—the room too hot—too many people to meet—too many names to remember. After a while, Shirley and I went down into the Smoking Lounge (oh, the imaginations of morticians, all of whom aspire to the respectability of theater-managers), where we sat and smoked and talked about other things and kept each other company. Then, coming down the stairs, I saw a face I recognized, but couldn’t place for a second.

It was Ann Charters, who had compiled Jack’s bibliography a few years before. She was wearing a large, knitted tam and a chic suede coat, and her alert, intelligent face, with the observant eyes and quick smile, was pale with cold, and her husband, Sam, whom I’d never met, was with her. He was a big, handsome man in a stylish, box-back overcoat, with the longish hair of someone older “on the scene”; a poet and a producer of Rock records, who exuded a sense of physical health, and the natural optimism of someone who is usually too busy to mope.

We all started chattering at once (death makes you talk, you talk so as not to think, you chatter as if you’d found a similar soul at the worst cocktail party of all time), and at one point Sam said: “I re-read your Kerouac chapter in Nothing More to Declare the other night, and it’s the best thing on Jack so far.” I felt a curious twinge in my gut, but didn’t recognize what it was, except that it wasn’t just my old reflex of being unable to accept praise. “You should do the book,” Sam said.” There’s going to be a book, and you’re probably the one to do it.” Twinge.

Later, the next afternoon, Sterling Lord, Jack’s literary agent and mine, would say to me: “You know, John, you’re really the one to do the book. You knew him from the inside, you were there when so much of it happened, but you can stand away from it all, too.” Twinge. “No, really, you’re the one to do it,” and the twinge became knowledge. The idea of the book—that combination of authorized biography and cool critical assessment without which America does not know how to think about its most challenging writers—revolted me. It seemed a coffin no less inadequate to contain the Jack I’d known than the one in which he lay.

______________________________

Excerpted from Gone in October: Last Reflections on Jack Kerouac by John Clellon Holmes. © 2022 Limberlost Press. Used with permission of Limberlost Press.

John Clellon Holmes

Born in Holyoke, Massachusetts on March 12, 1926, John Clellon Holmes wrote stories, poems, reviews, essays, and articles that appeared in major magazines and literary journals throughout the world. He’s perhaps best known for three novels—Go (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1952), The Horn (Random House, 1958), and Get Home Free (E. P. Dutton, 1964)—and the essay/memoir collection Nothing More to Declare (E.P. Dutton, 1967), a definitive work about the Beat movement and other eruptive post-World War II cultural shifts. These books were later followed by several more collections of poems and essays. His books have been translated into Danish, German, Italian, and Swedish, and have had wide circulation in the United Kingdom. He died of cancer at 62 on March 30, 1988.