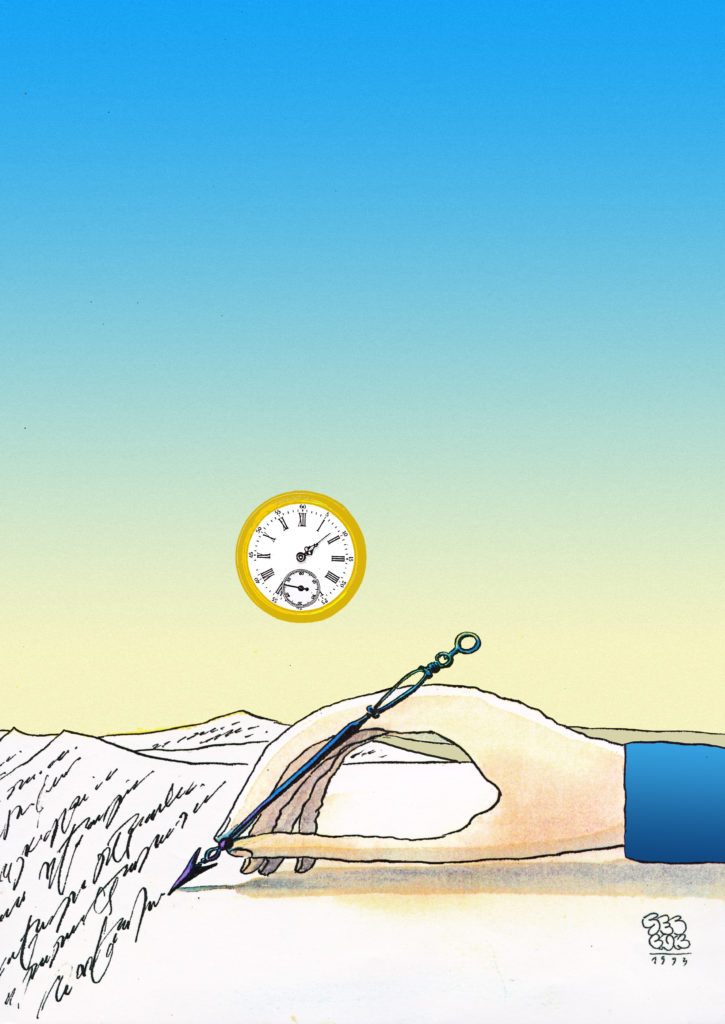

In a main square a large clock on the roof of the town hall told the time. Whenever a train from the country arrived—once a day, very early in the morning—there was a smart man standing in the square comparing the clock’s time with that of his own pocket watch. A shepherd who had just arrived by train in the town looking for work, asked the man what he was doing standing there for so long?

I’m waiting, the man explained. This is one of my jobs, checking the town clock. When the big clock stops, I have here—he pointed at his watch—I have here the right time, so the town clerk can reset the town hall clock correctly.

Does it stop often?

Several times a week, and when it stops, they consult me and I tell them the proper time, and they pay me. They pay me almost a dollar! Easy money! To tell the truth I have many jobs to do, too many. Look, I like your face. If you want, I’ll pass this one on to you. You can have the watch—it goes with the job—for just half a dollar!

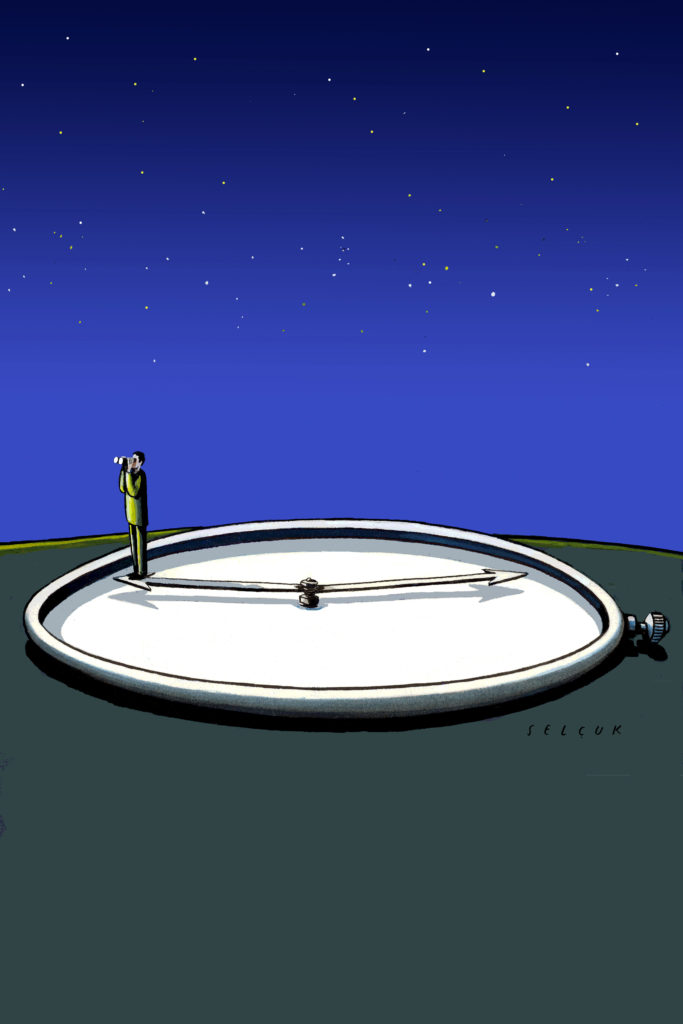

Narrative is another way of making a moment indelible, for stories, when heard, stop the unilinear flow of time.

Those who read or listen to our stories see everything as through a lens. This lens is the secret of narration, and it is ground anew in every story, ground between the temporal and the timeless.

If we storytellers are Death’s Secretaries, we are so because, in our brief mortal lives, we are grinders of these lenses.

A room needs an awareness of the passing of time. Otherwise it risks becoming inanimate. Or, to be more accurate, its silence risks becoming inanimate.

Patience, patience, because the great movements of history have always begun in those small parentheses that we call “in the meantime.”

So easy to forget how political practice often operates like a loom, weaving in two directions, the expected and the unexpected.

We’ll know when the time comes.

__________________________________

Extract from What Time Is It? by John Berger and Selçuk Demirel. Published by Notting Hill Editions (2019). All rights reserved.

John Berger

John Berger was a storyteller, essayist, novelist, screenwriter, dramatist and critic. He was one of the most internationally influential writers of the last fifty years, who has explored the relationships between the individual and society, culture and politics and experience and expression in a series of novels, bookworks, essays, plays, films, photographic collaborations and performances, unmatched in their diversity, ambition and reach. His television series and book Ways of Seeing revolutionized the way that Fine Art is read and understood.