I was pregnant with my daughter when my mother died. I didn’t know this then. If I had, maybe it would have made a difference.

If my mother knew she would soon have a granddaughter, maybe she would have tried harder to stay alive. “Something to live for,” people say, but my mother had much to live for already—a grandson, a nice son-in-law who cut her grass and liked her meatballs and listened to her stories.

She had me.

“I need you,” I told my mother in the hospital.

“I’m tired,” she said.

She said, “No. You don’t.”

By 40, I’d finally pulled the strings of my life together into something that looked like it would hold. What my mother meant—I had a good husband. A son. A steady job teaching writing at a university. A life.

“I was 40. Then I was fortier,” a friend wrote.

I’m fortier.

I can’t imagine when I will ever be old enough to stop being my mother’s daughter. I can’t imagine when I will ever stop needing her.

* * * *

Phelan, my daughter, isn’t named after my mother. She has my birth name, a last name for a first name. I thought it was pretty. I thought it made sense.

My daughter has my husband’s personality, but she looks so much like me. We have the same blonde hair, same green eyes. One day soon she’ll insist my baby pictures are her baby pictures.

I thought giving her that name was a way to honor roots. I always pronounce Phelan as Fay-Lynn. This is my daughter’s name.

At Catholic Charities, they said I had it wrong.

“The family says it Fee-Lynn,” the counselor said. She didn’t look up from the adoption-search forms I’d filled out, the ones she was examining for errors.

Fee-Lynn.

It’s not nearly as nice.

* * * *

I should have named my daughter for my mother, my real mother, though my mother hated her name and wouldn’t have wanted me to pass it on.

“It’s an old lady’s name,” she said.

My mother’s name was Alberta. She shortened it to Bertie, but it still made her wince.

Her maiden name was Bonde, switched from the Italian Bondi with an “i” so it would seem more American. My grandmother’s name was Ethel. Ethel, out of spite my mother believed, named her children as follows: Florence, Velma, Gertrude, Alberta, and August.

“One name more hideous than the next,” my mother said.

Most were named for friends, except for August, who was named for his father and made everyone call him Butch.

* * * *

My grandfather, August Bondi, was an orphan, too. His mother delivered him to an orphanage one day when he was nine or 10. She packed a small suitcase. Clothes, a child’s Bible. It was the beginning of the Depression.

She said she couldn’t afford to feed him. She said he was difficult.

She didn’t say she drank too much. She didn’t say she wanted her own life.

My mother said her father wouldn’t talk about it. She said he always made sure they had plenty to eat, even ice cream, three or four different flavors, gallon cartons lined up in the ice box when there wasn’t money for anything else.

I never knew my grandfather. I know he made bathtub gin to pay for food. I know a few pictures—a thin man, sad eyes like Andre the Giant’s, mugging a toughguy stance, paperboy cap down low, one pin-striped leg cocked on the fender of a black Ford.

I know he died on his birthday the year I was born.

“He would have loved you,” my mother always said.

Maybe I would have loved him back. Two orphans.

* * * *

How a mother could take her child by the hand and give him over to strangers, how she could walk away and not look back, I don’t know.

I don’t know what she told him, what she could possibly have told him, to make him stay and believe, in what?

That she’d come back.

That she wouldn’t come back.

That his life would be better either way.

* * * *

Or I do know.

Motherhood is a conflicted state, not clear and simple at all.

Very few mothers are monsters.

Joan Crawford, maybe.

* * * *

“You’re a good mother,” my mother told me the day I was weeping in her driveway.

My son Locklin was very young then, a year or so. I’d gone to the grocery store. He screamed the whole time. He thrashed and wailed and I had to hold my hands over his hands in the cart to keep him still.

He was a beautiful baby, but he cried so much and so long that I started crying, too. I cried over bills and junk mail and “Mister Rogers Neighborhood.” I cried over Oreo commercials, where fathers taught their children how to pull apart and dunk a cookie and scrape the icing off with their teeth. I cried in class, when I tried to explain to my students about the writer Raymond Carver, how, when a doctor told him he had cancer and would die, Carver thanked the doctor, “habit being so strong.”

I cried that day in my mother’s driveway when the grocery bag tore open and milk spilled and flooded the trunk. I knew no matter how I tried to clean it up, the milk would molder and stink and the car already smelled. It smelled like wet diapers and diaper powder and Butt Paste, a brown muddy-spearmint diaper-rash lotion, the only thing that worked. The car smelled like shit and carsick puke and the lingering grease from the fast food I ate because I was too tired to cook or eat anything else.

I smelled like all those things, too, all the time. I smelled feral, animal, desperate, everything I was.

“You’re a good mother,” my mother said, a gift, a mantra, a promise, like something she’d said to herself through the years.

She tried to help me, but I kept on crying like the child I was. My mother sopped up milk and sprayed the car with air freshener and took my son from his car seat and rocked and rocked and rocked him until he passed out, which is what he did instead of falling asleep.

My son never just fell asleep peacefully, like babies in commercials. He passed out from exhaustion, all that anger, all those built-up then let-go tears.

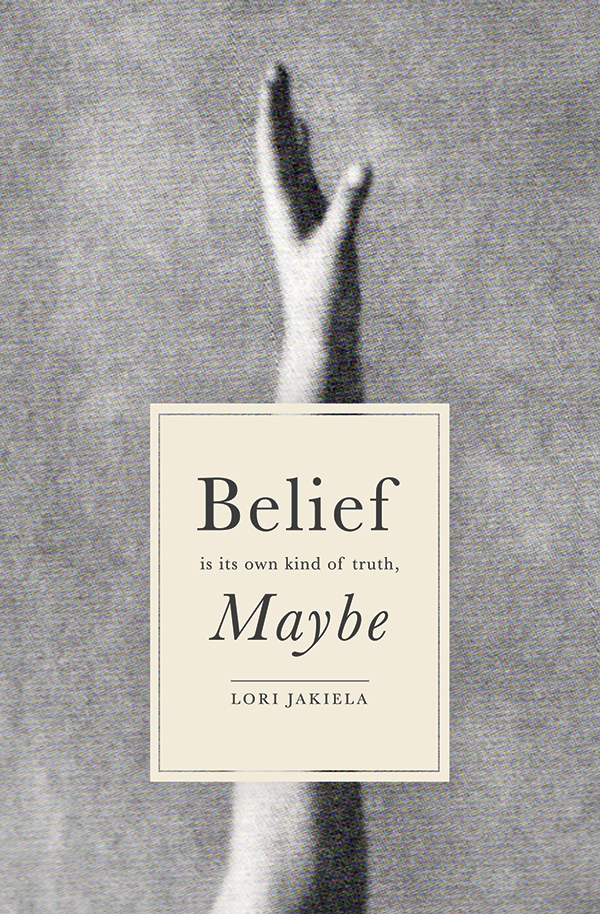

From BELIEF IS ITS OWN KIND OF TRUTH, MAYBE. Used with permission of Atticus Books. Copyright © 2015 Lori Jakiela.