All the Jappy girls are on a new diet. It’s called the Israeli Army Diet. I hear a couple of them talking about it at their lockers.

“It’s two days apples, two days cheese, then two days chicken,” Rachel Hoch says.

“And nothing else?” asks Maya Levine.

“Exactly. So the trick of the diet is—” Rachel looks over her shoulder to see if anyone’s listening. She sees me there and turns back. “The trick is that you get so sick of each food, you stop eating it by the end of the first day.”

“So what do you eat?”

“Nothing, that’s the point. That’s how you lose all the weight.”

“Wow.”

The bell rings and I close my locker. The two girls stay where they are, and I go to Jewish History. …

Yulia has saved me a seat in the corner. I spot her as soon as I come in. As I make my way over, I glance around the room, looking for Bradley Ruben. He’s talking to Josh Mellinger and laughing and, just as I’m about to turn away, he looks over, taking in—with one up-and-down swoop of his eyes—my synthetic-leather shoes, the secondhand sweater with the holes in the sleeves, my reddening face. Before I have time to smile or say something, he goes back to his conversation. Inside my school dress, I break into a summer sweat. When I get to my seat, Yulia can tell something’s going on.

“Are you okay?” she asks me in Russian.

Irina turns around to look at me. “Yeah, your face looks funny.”

“Okay everyone, quiet,” Mrs. Kansky calls out. Her skin is heavily powdered as usual, and today her eyebrows are drawn on with what looks like lead pencil. The long sleeves of her blouse hide the line of numbers on her arm that we all saw once, when she lifted her hand to write on the board and the cuff slipped down. “Daniel,” she says, though in her accent it is Dani-ell, “enough with the Game Boy. Good, thank you. Now let’s begin. Who’s brought in their testimonials?”

Last lesson we were doing the Spanish Inquisition, but Thursday is Yom HaShoah so this week we’re doing the Holocaust. Over the weekend, we were supposed to interview any survivors in our family, or find out what happened to them if they’re dead now, and today we’re supposed to tell the story to the class.

“Who wants to go first?” asks Mrs. Kansky. No one volunteers, so she chooses Josh Mellinger. He goes to the front of the room and she makes him put on his kippah. Then she tells him to tuck in his shirt. While he’s pushing the shirt under his belt, the top button pops off his pants, falls onto her desk, rolls to the edge and off onto the floor. He tries to stop it with his foot but it continues its arc until it disappears under the desk. Everyone laughs.

“My grandfather Isaac was nine years old the day he arrived at Auschwitz. He was separated from his family immediately—his two brothers, his mother, and his father—and he never ever saw them again. He didn’t get to say goodbye.”

Next up is Natalie Greenblatt. “The kapo liked my grandmother,” she says, her fingers twisting the dial on her TAG watch as she talks. “I don’t know why. But she always used to try and give her some extra food if there was any.”

“He found out later that his mother was gassed two days before liberation, and half a kilometer away from where he’d been.”

“She was sick for years after the war, and to this day her stomach is too weak to digest orange juice or the peel of an apple.”

One by one, the students who have stories get up to tell them, and the mood in the room changes. Everyone is dead silent, listening. The noise of kids outside shouting to one another on the quadrangle just creates a sense of hushed community inside our classroom. Even the blackboard dust floating in the sunlight near the window seems respectfully still.

All this is disturbed halfway through the lesson, when Rachel and Maya come to the door, giggling and apologizing over each other for being late.

“Sorry—”

“We were just—”

“She was just—”

“Shut. Up.” Everyone looks over to where Bradley Ruben is sitting, both hands resting calmly palms-down on his desk, glaring at the girls in the doorway. Rachel and Maya go quiet and slink into nearby seats, not daring to make eye contact with each other. Then Bradley picks up his pen and leans over his notebook, drawing something in the margin. Wisps of his hair fall into his eyes, and he sticks out his bottom lip and blows them away.

“All right, everyone. Let’s continue,” Mrs. Kansky says. She calls on Simon Herschenberg to read his testimonial, and everyone gives him their attention. Everyone except me. I can’t stop thinking about how much I love Bradley Ruben, how brave he is for saying what he said, and how I wish I had a sad Holocaust story to tell, so he would know I’m not so different from him and all the others.

* * * *

Yulia takes public transport home, so I walk up to the school buses by myself. It’s a warm day for April and in the bus park some older kids get into a water fight. Walking past, I get splashed with water from someone’s bottle. It rolls down my legs and into my socks. I look around but no one’s looking at me.

“Let me take off my sweater first,” one guy calls to another. “I’m all sweaty.”

“Yeah, you smell like a Russki,” a girl says, and people laugh.

There are twenty-nine school buses. I take number three. I stay close to the chain-link fence on my way down there. My right shoe squelches as I walk.

“Hi, Anya,” the bus driver says as I climb on.

“Hi, John.”

“Warm one, isn’t it? Lucky I got this air conditioner working again. My missus told me this morning it might rain. Melbourne weather for you.”

“Yes,” I say.

“I’m just hoping it lasts till the weekend. Go Dogs!” His mustache lifts to reveal a grin, and he laughs. I try to laugh back but it just sounds nervous. I walk halfway up the aisle and take a seat.

Five minutes later, when the drivers turn on their engines, all the kids outside hurry to end their conversations. They hand back each other’s Walkmans, kiss each other on the cheek, and yell “I’ll call you!” as they rush to catch their buses.

People pile on. The oldest kids head toward the back, touching the top of every seat as they go. A younger girl sits next to me. She lifts the armrest, swings her legs into the aisle, and spends the whole ride talking to a girl in the seat opposite.

The drive from Burwood to Caulfield takes forty minutes. My stop is one of the last ones. John opens the door for me and waves goodbye as I step down onto the sidewalk.

“Bye, Anya. See ya tomorrow.”

“Okay, John. Yes, thank you. Bye.”

Our house is the only single-story place on the street. The front garden is overgrown with long grass and a wayward rhododendron bush that hasn’t flowered in the two years we’ve been here. As I pull the rubbish bin from the curb through the gate, I hear the sound of “Hava Nagila” being thumped out on the piano. Inside, the house smells like frying fish.

“Hi,” my mother calls from the living room when I pass. “There’s sirniki in the kitchen if you’re hungry.”

“Okay,” I say.

The young boy she’s teaching doesn’t look up from the keys.

In my room I throw my backpack on the floor and fall back flat onto the bed. On the ceiling above me there’s a poster of Edward Furlong wearing a white undershirt and a scowl, torn from a magazine someone left on the bus last year. I roll over on my side and press my nose to the wall, breathing quietly as I remember. Bradley Ruben with his eyes on me. Bradley Ruben with his palms flat on the desk. Bradley Ruben with his fingers cupped around my breast, his tongue pushing its way into my mouth.

“No no. Like this, like this,” I hear my mother say in the next room. I hold the pillow over my head to muffle the broken English coming through the wall, and the sound of a clumsy kid making the same mistakes over and over again.

I had barely spoken to any of the Australian boys until two weeks ago. It was a Monday afternoon, and I had climbed off the bus to find Bradley Ruben sitting on the sidewalk, leaning up against someone’s fence and smoking a hand-rolled cigarette.

“Hey,” he said as I walked by him. Then he picked a piece of tobacco thoughtfully off his tongue.

“Hi,” I said, ducking my head down and pushing a strand of hair behind my ear.

“I was waiting for you.” He picked up his bag and followed me. “You’re good at chem, right?”

“Yes, I suppose, yes.” My face felt hot and was, I was sure, as red as Gorbachev’s.

“Well, I’m screwed for this lab report. Do you reckon you could help me? My house isn’t far. Just off Orrong.”

I knew my mother would worry but I went anyway. His house was enormous, one of only four on a dead-end street, and it was painted sky blue. Inside, everything was blue—the carpet, the banister, the frames around the family portraits in the foyer, even the backdrops in the photos themselves. He rushed to a switch and pressed a few buttons—“the alarm,” he explained—and then we stood there, listening to the hush of the air-conditioning and a television playing somewhere in the house.

“Come up,” he said at last. I followed him up the stairs.

His bedroom was the last one in a long corridor of closed doors. It was large and light, with a single bed beneath a framed poster of Kurt Cobain singing into a microphone with his eyes shut. A glass door led out to a balcony with a view of the swimming pool in the backyard. When I stood on my toes out there, I could see Port Phillip Bay on the horizon. The color of the water matched Bradley’s house.

“Is nice,” I said.

“It’s all right.” He shrugged. “This one’s really big but I liked our old place better.”

When we came back inside, Bradley shut the sliding door and pulled the blinds down. He went over to his bed and pressed some buttons on a remote control. He sat down and looked at me. “I wanna die next to you, if you’ll die too,” a man’s voice sang from the stereo. I wondered if I should get out my notes.

“Come here,” Bradley said. I went and stood in front of him. He tugged at the bottom of my school dress so I bent my knees and knelt down. Up close he smelled like smoke but his mouth, when it kissed me, tasted like green apple Warheads. I kissed back, distracted by his hand, which was moving from my waist, up my side, and then under my arm. He pulled his face away then and wrinkled his nose.

“Is it true that in Russia it’s so cold, you guys don’t even use deodorant?”

“Yes,” I said. “Russian winter is very cold.”

He tilted his head to the left and I made the same adjustment, and we started kissing again. There was more tongue this time, and his hand was moving faster, over my collarbone and down my chest until it rested firmly, finally, on one of my breasts. I stopped breathing for a moment, certain that he would be disappointed with my size, that he would notice I didn’t wear an underwire bra and would ask me to leave. But he didn’t say a thing.

I don’t know how long we stayed like that, kissing under Nirvana, with Bradley’s sweat mixing with spit around my mouth, his hand moving from one breast to the other. My knees were sore from kneeling on the carpet, and my shoulders ached from my book-filled backpack, which I’d forgotten to take off. I had never touched a boy before, so I don’t know how I knew exactly what to do next, when he unzipped his fly and lay back on the bed, his hands resting under his head.

Afterward, he pulled up his pants and said he had to study for his bar mitzvah.

“Did guys have barmis in Russia?” he asked me.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Is very difficult though. Maybe dangerous.”

“Crazy.” He stood and opened his bedroom door. I went out into the hall. “Do you need me to walk you?”

I pictured the front of my house, with its paint faded and peeling off, the antenna that had fallen over and now hung from the roof, tapping my window on windy nights, and the sound of Rachmaninoff wafting out from behind my mother’s lace curtains. “No, thank you, no,” I said.

“Okay,” he said. “Don’t tell anyone.”

“No.”

He shut his bedroom door. I heard him walk across the room, and then the music got louder.

Downstairs I went the wrong way and ended up in the kitchen, a big, bright room with blue marble countertops and a pretty girl standing in the center. She was shorter than me, but she was wearing a twelfth-grade sweater, and even through that I could see her arms were as thin as a child’s. Her eyes were brown like Bradley’s but her hair was curlier, and her cheeks were long and gaunt.

“Are you Brad’s tutor?” she asked, looking me up and down.

“No,” I managed. “Just from school.”

“Oh, okay.” I stared at the ball of bone pushing against the skin of her wrist as she pulled open a cheese stick. “Want one?” she asked when she noticed me watching. “There’s another box in the fridge.”

“Oh, no,” I said, walking backward out of the room. “Thank you.”

As I rushed through the foyer, I knocked a porcelain bluebird off a table with my backpack. It fell on the carpet but didn’t smash. I left it there and hurried out.

When I got home that day, the windows were closed and the house was silent. I found my mother in the bathroom, sitting on the edge of the tub, leaning over with her head in her hands.

“Mama?” I said. She lifted her face, which was paler than I’d ever seen it, her eyes rimmed in pink.

“Where were you?” she asked in English. It sounded so strange I almost laughed. “I’ve been vomiting, and sick with worry,” she said, this time in Russian.

“I was at a friend’s house,” I told her, glimpsing a slice of my reflection in the mirror above the sink. My ponytail was loose in its hair elastic and my right cheek was rosier than the left.

“Which friend?”

“Rachel Hoch,” I lied. “A girl from school. She wanted help with homework.”

“How was I supposed to know that? You’ve never been late before. I thought someone took you.”

“Who would take me?” I asked. But she turned her face away and I understood, without knowing why, that I should shut the bathroom door behind me and go to my room.

My mother’s student has gone home now, and my father is back from work. He’s sitting at the table in the kitchen, his blond curls tight on his head, the armpits of his shirt wet with sweat.

“They call this autumn?” he says. “It’s over eighty-five degrees out there. These people don’t know autumn.”

“You’re telling me,” my mother says from the sink. “The postman was wearing shorts today. Tiny blue shorts with knee-high socks. It was almost obscene. I had to look away.”

“Did you have that test?” my father asks me.

“Friday,” I say.

“It’s maths, isn’t it?” my mother says. “You’re good at those things.”

“Yeah, if you study a little, you’ll have no problem.”

“Smart girl.” My mother hands me a bowl of soup and puts one in front of my father. She sets a smaller portion on her own place mat, then goes back to the sink.

My mother is tall, a full head taller than my father, with a thin nose and light-blue eyes, and a waist so small she has to tie her apron straps around it twice. When she was my age, growing up in Russia, she thought one day she would be a famous concert pianist. My father as a boy, growing up just two towns away from her, dreamed of marrying the most beautiful girl in the world.

“At least one of us got our wish,” my mother says bitterly whenever this topic comes up. Then my father always laughs, and she lets him pat her hand.

Back at the table now, she places a plate of fish and a kugel on the doily in the center, and takes her seat. “Well?” she says. “Eat.” My father has already finished his soup and is reaching for the kugel, but I push my own bowl away. I get up and go to the fridge, holding the door open with my hand and sticking my head right deep inside where the air is cool and quiet. I close my eyes.

“What are you looking for, Anyishka?” my mother wants to know. From where I am, her voice sounds far away. The fridge is full of jars and bowls of leftovers from other dinners, all covered neatly in aluminum foil.

“Why don’t we throw some of this food away?” I click my tongue in irritation. “Don’t we have any apples? Or cheese?”

“What? You’re not hungry? My food’s not good enough for you?”

“All those years going without,” I hear my father say. I know without looking that he’s slowly shaking his head. “Cordial instead of orange juice.”

“And newspaper instead of toilet paper,” my mother joins in.

“Uch, don’t remind me,” he says.

“Is that true?” I ask, standing up straight.

“You don’t remember?” my mother asks. “For years our backsides were black from the ink. We left fingerprints on everything we touched.”

“Wait one second,” I say. “Let me get my notebook.”

My father refuses to get a cordless phone. He says they’re too expensive and that by the end of the 1990s, everyone who has a cordless phone will have brain tumors or ear cancer. So when Yulia calls after dinner, I have to pull the cord from the kitchen out into the hallway, past the bathroom, around the door frame where my mother marks my height in pencil once a month, and into my room.

“What are you doing?” she asks.

“Homework.” I push the door shut and lean back against it, sliding down to the floor.

“Maths?”

“Jewish History.”

“Can you believe that Bradley guy?”

“I know,” I say. “Those Japs were silent for the rest of the lesson.”

“And I thought Maya was his girlfriend.”

“Really? Are you sure?”

“Why?” she asks. “Do you like him or something?”

“Who? Bradley? No. Why, do you?”

“No.” We sit in silence for a moment.

“What’s that noise?” I ask her.

“My mum’s crying.”

“Is your dad drinking?”

“No, she’s watching 90210. They’re closing down the Peach Pit. She loves that crap.”

“Hey, Yuli?”

“Yeah?”

“Are you planning to write a testimonial?”

“No, I’m doing the ESL questions, then I’ll study for maths. And then I’m going to sleep to dream about Rachel Levine’s face when she got told to shut up.”

“It’s Rachel Hoch,” I say. “Rachel Hoch and Maya Levine.”

“Who cares? Both their faces went pale. You could see it happening, even under the fake tan.”

* * * *

In school the next day, I feel so nervous I think I might be sick. After lunchtime, I go to the toilets, cover the seat with paper, and sit down. I take out my notes and read through them. A group of girls come in and stand by the sinks. Under the cubicle door, I can see their Airwalks and Clarks crowding around the mirror.

“I’m starving,” one of them says.

“I know. This diet sucks.”

“Apples and cheese were okay. But I could not do chicken for breakfast.”

“We should go to McDonald’s for nuggets after school.”

“Totally!”

“I can’t, I’m going shopping for my brother’s barmi.”

“Why don’t you wear the dress you wore to my brother’s barmi?”

“I can’t. It’s, like, too small and so Russian. Anyway, how do we even know the diet works?”

“Have you ever been to Israel? Those soldiers are, like, hot.”

When the bell rings, I come out of the stall and wash my hands. One of the girls smiles at me in the mirror. It’s the one from Bradley’s kitchen.

“Hey,” she says.

“Hi.”

“You haven’t come around again.”

“No.”

All the other girls are staring at me in the mirror now, too.

“I wouldn’t take it personally,” she says. “I mean, I love my brother, but he has pretty boring taste in girls. Maybe when he’s older, he’ll want someone, you know, a bit different.”

“Okay,” I say.

“Okay. See ya.” She gives me a little wave in the mirror, and then she leads the other girls out of the bathroom.

“Who is that?” one of them whispers. I don’t hear her answer.

Bradley Ruben is giving his testimonial when I get to class. He glances up when I come in, then looks back down at his notes.

“Sorry,” I mutter. This is the first thing I’ve said to him since the day at his house.

“In January 1946, my grandfather found out that his first wife and daughter had perished in Majdanek. By May, my grandmother had received her own bad news. They got married the following year and by 1949 they were in Australia and my dad was born. Thank you.” Bradley folds the piece of paper he’s holding, and goes to his desk. It feels like we should clap but no one does.

“Right, thank you,” says Mrs. Kansky from the back of the room. “Anyone else?” The class sits in silence. “No?” I hold my breath and imagine I’m a different person. Then I raise my hand.

It takes her a minute to see me. “Anya?” The class turns to look. I stand up, swaying slightly.

“What?” I hear Irina say under her breath. I push my chair back and move to the front of the room. My throat feels dry and chalky. Everyone is watching me now, except for Bradley Ruben, who is bent over his notebook, pen in hand, drawing something in the margin.

“After Jews were allowed from Russia in 1989, my mother, my father, and I lived in a flat in Vienna for eleven months, waiting for a visa for here. We were eight people in one small flat, all from Russia or Ukraine, and the toilet was often not working so were sometimes very sick.” I hear a rustle in the room then. Someone coughs, or maybe laughs. I don’t look up. “We had food given to us, not very much, but we made it so it could be enough. My mother in this time got pregnant two times. She had to have abortions because there was no moneys or room for babies.”

“Anya,” Mrs. Kansky says.

“Once, the abortion came wrong and my mother had an internal ha—ham—hemorrhage.” I stutter over the word and when I finally get it out, Mrs. Kansky is by my side.

“Anya,” she says again, her hand on my arm now, her bracelet cool against my skin. “This story is from more recent years. That’s not what we’re discussing this term.” Her voice is quiet and she’s looking right into my eyes. “Maybe you can tell it later in the year, but I think right now you should go and sit down.”

So I do. There is nothing else to do so I go back to my seat and put my hands on my desk and stare at them. Yulia passes me a note but I don’t feel like reading it. I leave it there, folded up next to my pencil case. And though the class continues, I hear nothing for the rest of the lesson but a low humming noise in my ears, like an airplane stuck in midair.

After school, Yulia walks with me to the buses. There are discarded chicken bones on the quadrangle and they crunch under our feet as we go. In the sports hall kids are arriving for detention, and on the oval the football players are already doing suicides. At the bus park, we stand outside the gate. Yulia lets me drink some of her chocolate Big M while the rest of the school files past.

“Why did you do that?” she asks me finally. “We never talk in Jewish History.”

I shrug and just as I do, I feel a hand on my arm.

“Hey,” Bradley says. He has a cigarette tucked behind his ear. For a second my heart feels like it’s trying to escape my body. “Was that a true story?”

“From the class?” I say. “Yes.”

“That’s fucked up,” he says. Then he breaks into a grin. “Sorry, I don’t know why I’m laughing.”

“Brad,” calls Maya Levine. She’s standing a few feet away with Rachel and Josh. “We’re going to the shops. Are you coming?”

“Yep.” He looks at me with a straight face, but then he looks over at Yulia and bursts out laughing again. “Sorry,” he manages to say. Then he turns and jogs to catch up with the others.

“What an asshole,” Yulia says. “I wish his mother had an abortion.”

I stick my thumb through the hole in my sweater and squint into the afternoon sunlight. “You know what?” I say. “They’re right. We do dress like Russians.”

“What?” she says, although I know she heard me.

“And we stink.” I turn to look at her. “It’s disgusting. We stink.”

She stands and looks at me for a long moment. Then she takes her drink out of my hand and walks away without a word, leaving me to face it all on my own, and all over again.

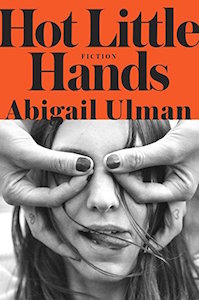

From HOT LITTLE HANDS. Used with permission of Spiegel & Grau. Copyright © 2016 by Abigail Ulman.

To win a copy of HOT LITTLE HANDS, enter here.