Jessica Gross on Writing a New York Novel as an Ex-New Yorker

How to Get Back in a New York State of Mind

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In early 2019, when I was single and living in New York City, I started writing a novel about a woman who was single and living in New York City. By the end of that year, I’d fallen in love with a man who lived in West Texas; when COVID hit a few months later, I joined him there. We officially moved in together later that year; we got engaged and then married; we had a daughter and bought a house.

Meanwhile, I continued to write a book set in New York City, where I’d lived for all 13 prior years of my adulthood, but which was very different from my new home. Lubbock is flat, brown, windy, dusty, spacious, cheap, friendly, and very quiet. (A friend of mine here compares it to a sensory deprivation chamber.) New York City is colorful, noisy, aggressive, exciting, claustrophobic, jagged, and highly stimulating.

At first, imagining myself back into New York City wasn’t hard. Even during COVID, my husband and I drove there by car with our dog, first to move my stuff out of my apartment in Brooklyn, then to visit family who still lived there. Even when we were in Lubbock, New York was a recent enough memory that I had no trouble getting it on the page.

But as I became pregnant and had a daughter, and as our dog became older, traveling so far became harder, and we visited less and less. Time ballooned between my New York and Lubbock lives. The further into my past New York receded, the more help I needed to remember what living there had been like.

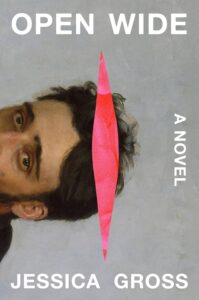

I thought about re-setting the book somewhere else, but it didn’t take long for me to dismiss the idea. Beyond the personal—I enjoyed spending time on the streets of New York City in my mind, if I couldn’t be there in person, plus I knew New York more intimately than any other major city—it felt like the perfect setting for this particular novel. Open Wide’s protagonist hosts a radio show, so the book needed to be set somewhere with a vibrant public radio scene. She’s also afflicted with the compulsion to record constantly, “collecting sounds the way other people collect stamps,” so I needed her to live somewhere with lots of conversations to overhear. (If Olive lived in a place like Lubbock, she wouldn’t be able to record passing conversations on the street—she’d record the sound of wind, some birds, the occasional car passing by.) Olive meets her boyfriend by chance, something that of course can happen anywhere, but is so much more likely to happen in a place with many strangers to meet and things to do. Olive is also odd and chaotic, and I liked the way New York mirrored her energy. Her partner, Theo, is weird, too, and New York offered the perfect canvas for his particular flavor of eccentricity.

For all these reasons, New York City felt like an ideal setting for Open Wide. But how to conjure New York on the page as the city’s textural details receded from my memory?

I’d been lucky enough to interview, in 2015, Colm Tóibín, who described writing Brooklyn from Ireland. He told me he’d sent an email to someone living in Brooklyn, asking him to tell Tóibín what was going on that day. “He said it was so cold in Brooklyn that people had their faces completely covered and you could just see eyes coming towards you on the street,” he told me. “And so I put that straight away into the book. I just needed one more detail for that day that was completely observed and right.”

Given that my novel’s protagonist is a radio host who’s obsessed with sound, I copied Tóibín’s technique with a slight alteration: I texted, emailed, and called friends in New York and Boston, a similarly busy city, asking them to tell me the sounds they heard as they were walking around. One, in New York, heard the jingle of a pedicab and the beeping of a maintenance cart as it backed up in the park. Another, in Boston, heard air conditioners humming and silverware clanking as she passed a restaurant’s outdoor-dining space. Another, in New York again, heard the tinny sound of music blasted from an iPhone from far down the street.

These once-daily noises had escaped my memory. So had the kind of detritus one finds on the subway, a detail I needed for a part of the novel I won’t spoil. One of my editors at Abrams, Abby Muller, noted that the debris I’d described in a draft of the book—hair ties, a necklace, an old tooth in a little pillow meant for the tooth fairy—was far too quaint.

I texted, emailed, and called friends in New York and Boston, a similarly busy city, asking them to tell me the sounds they heard as they were walking around.

She reminded me that New York subways are home to water bottles full of other people’s weird-colored backwash, dead rats, and mystery liquids that pool on the seats. I put the water bottles right into the book, and used Abby’s suggestions as a springboard to imagine other subway rubbish: a scrunchie with a few hairs still stuck in it, fingernail clippings, a purple glove with a coffee stain, a MetroCard with the words FUCK U OK? on the back, a half-eaten Ring Pop. Fueled by Abby’s prompt, my details became properly gross, bizarre, and specific.

In another part of the novel, I’d had Olive and Theo go to dinner at a restaurant in his neighborhood, Brooklyn Heights, called Eileen’s. This restaurant does not exist except in my imagination, but it was the kind of place I loved to visit when I lived in New York: food that’s excellent but not ostentatious, a stylish but relaxed atmosphere, hosts who know regulars by name. My other Abrams editor, Ruby Pucillo, urged me to pick a restaurant that actually exists, which triggered my ex-New Yorker insecurity: I had no idea where was cool anymore. Ruby, a New York City native, suggested Inga’s Bar, which I’d never heard of, as it had opened after I moved away. She assured me that Inga’s satisfied every need for the scene I was revising. Not only was it in Brooklyn Heights, Ruby emailed, but it checked every other box, too: “fashionable modern American food that still feels homey, candlelit tables covered in butcher paper, and a categorically ‘this is my neighborhood spot’ vibe.”

Beyond elevating my book, garnering select details via reporting rather than personal experience had the unpredicted effect of making writing fiction easier. It removed the step of translating the city from lived experience into something on the page. (I should note that translating lived experience into words is one of the most pleasurable parts of writing fiction, and I’m glad a lot of “my” New York made it into the book, too.) The details my friends and editors handed to me were, for all intents and purposes, fictional. They weren’t my details. They were already other people’s sounds and sights, transported to me from their very separate worlds.

Perhaps my next novel will be set elsewhere—in Lubbock, or someplace I’ve visited a lot (New Orleans), or someplace I’ve visited a little (Boston), or someplace I’ve never been to at all. A book set in Lubbock, say, would be a very different kind of book, one with the smaller circumference of village life. Perhaps there’s some drama in the town’s sole synagogue, which has fewer than 50 people. Perhaps my craft challenge, this time, would be introducing stimulation from the inside out. But for Open Wide, I’m glad I set the book in New York, to fuel both my own imagination and my narrator’s journey. The truth is that certain books should be set in a big city like New York because of what it offers: stimulation and serendipity and constant hits of the truly strange.

______________________________________

Open Wide by Jessica Gross is available via Abrams Press.

Jessica Gross

Jessica Gross's writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The New York Times Magazine, and The Paris Review Daily, among other places. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School, a Master's degree in cultural reporting and criticism from New York University and a Bachelor's in anthropology from Princeton University. She has received fellowships in fiction from the Yiddish Book Center (2017) and the 14th Street Y (2015-16), where she also served as editor of the LABA Journal. She currently teaches writing at Eugene Lang College at The New School. Hysteria is her first novel.