Jessica Francis Kane on Penelope Fitzgerald in Mexico

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

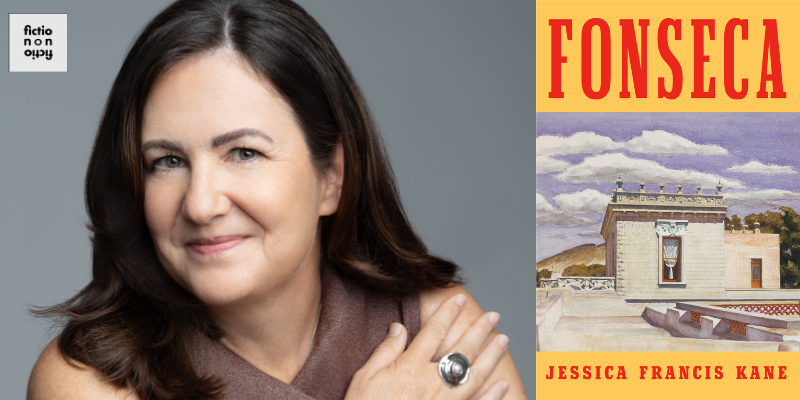

Novelist Jessica Francis Kane joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss her new novel Fonseca, which fictionalizes writer Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1952 trip to Mexico. Kane talks about imagining Fitzgerald in her mid-thirties, before she had become a novelist, when she was living a financially precarious life and editing a journal with her husband Desmond. Kane reflects on Fitzgerald’s decision to travel to Mexico with her son Valpy, a prospective heir for sisters there who are distantly connected to their family. Kane explains how she came to correspond with Fitzgerald’s children and the choice to use those letters as part of the book; her belief that the trip had a formative effect on Fitzgerald; “following the plot” based on the available facts; and introducing historical speculation, like an acquaintance with painter Edward Hopper, into the storyline. Kane reads from Fonseca.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

Fonseca • Rules for Visiting • This Close • The Report • Bending Heaven

Penelope Fitzgerald:

“Following the plot” | Penelope Fitzgerald | London Review of Books • Our Lives are Only Lent to Us | Penelope Fitzgerald | Granta Magazine • The Means Of Escape • Offshore • The Blue Flower

Others:

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life by Hermione Lee

“The Peripatetic Penelope Fitzgerald” | Lucy Scholes | Granta

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH JESSICA FRANCIS KANE

Whitney Terrell: This novel seemed to me while I was reading it to be in part about disorientation. So let’s begin by orienting the readers and our listeners as much as we can. Could you just explain to us the basic premise of Fonseca? Why does Penelope Fitzgerald go to Mexico in 1952 and who does she go to the meet? And what does she find when she gets there?

Jessica Frances Kane: If we’re to believe Penelope Fitzgerald herself, she goes to see about the possibility of inheriting a legacy in 1952 at a very difficult time for her family. The family was on the brink of bankruptcy, financial catastrophe. She receives letters from two elderly Irish expats living in northern Mexico off of the proceeds of a family silver mine. And as she understands it from these letters, they don’t have any heirs, and are interested in finding someone to inherit their money. And they’re interested in her son, Valpy. So she travels to Mexico with Valpy in 1952. She is a young mother. She has two children, Valpy, who’s six, and Tina, who’s two, and who she leaves with family. And she and her husband, Desmond, are editing a literary journal that is very highly regarded but is not making any money, and so she goes off to northern Mexico, stays three months to, as we understand it—we have very few facts about the trip, but she is there to see if Valpy may inherit the legacy from these family friends. It’s a very odd thing.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: It’s an amazing little interlude in her life. I knew very little about Penelope Fitzgerald’s life during this period, because she was in her mid-30s when she went to Mexico, and she was much older when she published her first novel, which we’ll talk about later. But I was reading, as Whitney was saying, parts of her situation seem disorienting and fantastical, and there are moments where she’s like “Why is there this magical haze?” But also the basic logistics of the story, the framework of it, is true, and those logistics are in a piece that she wrote for the London Review of Books in 1980. Can you talk a little bit about that essay and how you first encountered it?

JFK: I read Hermione Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald, which came out in, I believe, 2014 in the U.S. The Mexico trip is mentioned in the book, but it’s given half a page, maybe a page at the most. Hermione Lee as a good biographer, checked ship manifests and knew that, yes indeed, they had crossed the Atlantic on the Queen Mary and they had taken a Greyhound bus from New York to northern Mexico—

WT: Such an insanely long trip, first of all. I mean, that’s just bonkers!

JFK: It’s funny you say that because the Mexico trip is mentioned in the biography, given about a page, and it did not strike me at the time—as much as I love Penelope Fitzgerald, at that time, I would have told you she was my favorite author. I had read all of her novels. I recommended her to everyone I knew. I read the biography, and I was not struck by the Mexico trip. I was struck by the Mexico trip when I read an essay by Lucy Scholes that appeared in Granta in the summer of 2017 and Lucy, in that essay very vividly highlights just what a crazy trip it was, how hard it would have been for a woman alone in 1952 to make that trip. It’s a hard trip to make today, three months pregnant, a long Greyhound bus ride with a six-year-old.

So I read Lucy’s essay and full stop said, “Wait a minute. What? Why don’t we know more about this?” She was 36, she wanted to be a writer but was not doing the writing that she hoped to do. I began to look into it and thought, “I think there’s a story here.” And I should say there’s an essay that took me to “Following the Plot,” which is the essay that Penelope Fitzgerald wrote in 1980 that you referenced, Sugi. It’s a craft essay she’s writing about plots, various novel plots, and how well they work, but in this essay, we get a few paragraphs that seem to set the scene for this story of Mexico that she didn’t write, and I just decided to follow the plot.

WT: It starts, “Suppose I were to try to write a story, which began with a journey I made to the north of Mexico, 27 years ago, taking with me my son, then aged five. We were going to pay a winter visit to two old ladies called Delaney who lived comfortably in spite of recent economic reforms on the proceeds of their family silver mines.” That’s a very interesting way to start a craft essay.

JFK: I think it’s because it’s a plot. A little further along, there’s a sentence about how sorry she was to leave the Mexico plot behind, for what she considered the natural energy that it had. So I think this was a plot, a novel plot she’d been thinking about using most of her life and didn’t. I think that’s why I became so interested in it.

WT: So her son, Valpy. As a person who has a name that people think is weird and which I love. I’m very curious about the name Valpy, which I have not previously encountered.

JFK: It’s a family name. He’s actually Edmund Fitzgerald.

WT: A nickname? It’s not on his birth certificate or something?

JFK: I believe it’s a nickname, yes.

WT: So he’s a character in the novel. He appears as a six-year-old. The real Valpy is alive. We could, I guess, ask him what he knows about his name. He has sisters, Tina and Maria. Tina was left behind with her grandparents, as we said, and Fitzgerald arrived in Mexico pregnant with Maria. You could talk to these people, these very living people, during the writing of this book, and parts of their letters appear in the book. So could you talk about how their input contributed to the final form of Fonseca?

JFK: So I had started work on the novel, and actually it was going quite well for me. I felt I was writing quickly, unusually fast. I sold the book based on a couple of chapters. I was thrilled. I told my editor, “I think I’ll have a draft in a year.” That was the summer of 2020. That September, I got an email from Terence Dooley, who is the literary executor of the Penelope Fitzgerald estate, and also was her son-in-law. He is married to Tina, and the family had seen news of the sale of this book, and said that they were very interested and would like to be in touch. So I was terrified. I completely stopped writing. I put everything I had into my response to Terence, trying to explain what I was doing and why I was taking it on and what her work had meant to me. I showed this to my agent and editor before I sent it back to make sure they thought I was on the right track here. And they said, “Yes, this is what we’ve got to do at this point. And this, this could be a good thing. Don’t panic. We’ll see how they respond.” And I won them over.

That first letter that appears in the book from Tina is one of the first responses I received after I responded to Terence. In that note to me, she finishes with a sentence that gave me so much confidence. She said that she believed in her mother’s books fact and fiction was very blurred and she said, “You push on.” And so I did. I had their blessing. They even invited me to ask questions. We corresponded by email for five years, and I wove some of their responses into the book in order to tell the story with that time perspective. So there’s the narrative of 1952 as I imagined it happened and then there are the letters written to me now answering questions about their mother and who she was and what they remember about her and the trip. So you have this dual perspective.

VVG: It’s really an amazing strategy. It articulates that gap between the fact and the fiction so beautifully and strangely in a way that I really love, and it’s part of the extraordinary feel of the book. You’ve been talking about historical antecedents of the novel, and to talk about its literary antecedents, there’s something refreshing and unique in the way that you convey the space of Mirando, which is the Delaney sisters’ house, and Penelope’s reactions to it, her questions about its potentially surreal or magical aspects. Valpy has questions about this too. And of course, Fitzgerald is known for entwining fact and fiction, as you say, blurring it. I wonder if you could talk about how you imagined her reaction to the dreamlike space of Mirando.

JFK: I had two things I was working with. I had the essay we’ve discussed already, following the plot. Then there is a short story. There’s one short story she wrote called, “Our Lives Are Only Lent to Us.” She wrote this story in the late 1950s after she returned from Mexico, and it seems to me to be set in a space that is like Fonseca. So I was able to, in many ways, overlay my story onto that story, because that story is also about an expat community in northern Mexico. I think that may be her one and only attempt to fictionalize her experience there. I think to get to your question Sugi, this was a moment in her life where she was very worried about her home and her family and what would become of them all, and whether she would ever be a writer. But at this moment, she finds herself very far from home. She also finds that she’s in a space that’s very, very different. She’s an Anglican in a Catholic country at Christmas time. She certainly has the responsibility of having traveled with her son, but many of her other responsibilities are far away. Desmond, her husband, had returned from the war, not physically wounded, but mentally damaged, and was becoming an alcoholic. Those were major concerns, the financial issues, but she’s far away from all of that. My theory is that this was a little window of time where she had some freedom that she would have really relished.

While relishing that freedom, she’s also observing a clash of culture. She’s in an expat community in northern Mexico. The silver mines have recently been nationalized, but obviously there’s a wealth disparity, there are two cultures living side by side and misunderstanding each other. In her own novels that she will go on to write 25 years from this time, she is so good at that kind of misunderstanding, finding the comedy and the tragedy that is in that sort of environment. My theory is that she took in all of that atmosphere during this period, and that it informed what she ultimately later wrote.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Jessica Francis Kane by Beowulf Sheehan.

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.