Jerald Walker Gets a Bad Haircut… and It All Goes Downhill From There

Whatever You Do, Stay Away From the "Kaleshion"

Kaleshion isn’t a word in the dictionary. It’s a word on your barber’s wall, handwritten beneath a photo of a bald head. There are other photos of heads up there with made-up words to identify their haircuts, but your father never selects those because they require hair. Male preschoolers with hair, your father believes, is a crime to which he’ll no more be party to than genocide.

Your friends’ fathers feel similarly, so your friends are bald too. But when they turn seven or eight and certainly by nine their fathers let them try different styles, while yours keeps making you get a kaleshion. He makes you get one until you are ten. What’s the deal with that? You don’t know. All you know is he relaxes his stance in the nick of time because it’s 1974 now and the Afro is king. Grow yours the size of a basketball. Swear on your grandmother’s grave that the kaleshion is behind you forever.

It’s never a good idea, unfortunately, to swear on your grandmother’s grave. One summer day, for instance, when you are 26 and have just moved to a new neighborhood, try out the barbershop near your apartment. It’s 1990 and the Afro long since gave way to the Jheri Curl, which gave way to flat tops, which you are not particularly fond of so you wear your hair an inch long all around. As you sit in the chair tell the barber you’d like a trim. Close your eyes. Relax. Nod off after a while but be startled awake when for some reason the clippers graze your upper lip.

Ask the barber, “What are you doing?” and when he says, “Tightening up your mustache,” respond, “Don’t touch my mustache,” but he says, “It’s too late.” Then he says, “I’ll just finish this up,” as you wonder, “What’s this guy’s deal?” and his deal is he’s incompetent, though you don’t know to what extent because the mirror is behind you.

But when he spins the chair around you are surprised to discover the mirror is actually a window, through which you see a man in a barber’s chair staring back at you, and yet, somehow, the barber standing behind this man’s chair is also standing behind yours, which means, in all likelihood, this man is you. It’s amazing the difference a kaleshion can make.

“So,” the barber asks, “what do you think?” and you think to punch him but instead refuse to pay. He orders you to leave and bans you from returning, which is a misuse of the word ban. You can’t be banned from doing something you’d never do. That’d be the same as you being banned from eating frog legs or skydiving or from still wearing a Jheri Curl like the guy at work you are about to dethrone as the office laughing stock, though maybe, it occurs to you as you walk home, you can mitigate this fate by shaving off your new pencil mustache.

Lift your driver’s license to the window. Press it against the glass. Watch your girlfriend squint at your photo, then at you, and then again at your photo.Start to jog with this thought in mind though you would have done well to walk because it’s sweltering outside and you haven’t jogged in a while. Cut through an alley to shorten the distance, but even with that you arrive on the back porch of your third-floor apartment breathless and sweaty, much like, one could imagine, a drug addict about to commit a burglary.

Your girlfriend imagines this. After parting the curtains she screams and ducks away from the window. Shout her name as you pat your pockets for the keys that are on the kitchen table, then realize she can’t hear you because she’s in the front room, where the phone is, calling the police. Don’t panic; all you’ll have to do is tell them about the incompetent barber. Take out your driver’s license in order to illustrate that your new face is also your old face.

If at least one of the officers is black he’ll see the resemblance, but the white one, like your white girlfriend, whose fingers have just parted the curtains again, will give you the stink eye. There is a high likelihood both officers will be white, however, which means weapons could come into play, so either convince your girlfriend you are her boyfriend or run.

Lift your driver’s license to the window. Press it against the glass. Watch your girlfriend squint at your photo, then at you, and then again at your photo. Beg her to let you in. A voice in your head orders you to get the hell out of there just as something in hers clicks; one hand cups her mouth, the other releases the curtain. The deadbolt and your fate turn.

Moments later, while shaving off your mustache, vow to never set foot in another barbershop. This doesn’t improve your mood so try another approach at your favorite bar. You feel better during your third cocktail, enough, even, for you to tell the bartender what happened. He doesn’t believe you. Lift your baseball cap. When he bursts into laughter you can’t help but join him. It is funny, after all.

Repeat the part about seeing the stranger through the window and laugh some more. And when the bartender, who knows you’re an aspiring writer, says this would make a good story, smile and say you definitely intend to write it someday.

Write a lot of other stories first, though, which earns you publications, a faculty position, your first book contract and, after many years, an invitation to read at a prestigious literary conference. According to the invitation, there are some notable writers scheduled to participate, one of whom is quite famous. This is a big deal. This is huge! It could mark your arrival as a serious man of letters, and it’s too bad, in a way, that your girlfriend isn’t around to see it.

She was supportive of your early efforts, even serving as your copy editor, an arrangement you’d projected far into a future where you’d discuss comma splices in your hospice, though perhaps you should have taken her attempt to have you arrested as a bad omen. That happened 15 years ago, a few months before you broke up. A lot has changed since then. One thing that hasn’t changed, though, is your self-imposed barbershop ban.

This is the correct use of the word ban because, who knows, maybe one day you’ll lift it after growing tired of the split-ends and generally scraggly appearance that results from you cutting your own hair. And you might have to start taking your sons to a barbershop when they realize that their hair, which you’ve cut since they were babies, doesn’t have to look like this either. But at ages six and eight they’re still too young to pay attention to such things, and you’re still wary of barbers, so every couple of weeks you break out the clippers.

Each of you gets the same style, a conservative quarter-inch cut that speaks of sophistication and a desire not to scare white people. You call it The Obama. To achieve it, simply use the #1 clipper guard on the top and the #1/2 for the sides and back. Sometimes you tease your sons by saying you can’t find the clipper guards so they’ll have to get kaleshions, and when they jump from the chair and run you chase them around the house, all of you laughing wildly.

It’s a good time. You did this for a while this morning but now, after they’ve received their Obamas, it’s time to give yourself yours. Make this your best effort. The literary conference is tomorrow.

Start on the crown of your head and work your way forward, as you always do, but this time scream because the #1 guard has just tumbled before your face and landed in the sink, followed by a clump of hair. Lean towards the mirror to stare at your long strip of pale scalp. Whisper, “Please God, no, please,” but God cannot help you.

Nor can your wife, who runs to the bathroom and, much like your girlfriend all those years ago, stares at you with a hand cupping her mouth. Your sons burst into the room. They want to know what the screaming is about. Your wife, speaking into her palm, says, “Daddy’s giving himself a kaleshion.”

The boys want to see. Reluctantly bend towards them. They erupt in laughter, as if, you imagine, you have just stepped to the podium to give your reading. Shoo them away. Try to convince yourself it’s not as bad as you think but the truth of the matter is conveyed by your wife’s stink eye. She lowers her hand and asks, “What happened?”

That’s simple: the grandmother on whose grave you swore all those years ago reached from the heavens to flick off the clipper guard. But don’t say this. Say you’re not sure. You are sure, however, of what must be done. Ask your wife for the shoe polish.

“You can’t,” she responds, “wear shoe polish on your head.”

“Why not?”

“Because that’s insane.”

“You have a better idea?”

“Yes. Shave the rest of your head.”

Look horrified and say, “Are you crazy?”

“You have to,” she insists.

Remind her that the important literary conference is tomorrow.

“Exactly,” she responds, and a stalemate is reached.

Twenty-four hours later, arrive at the important literary conference. As you enter the auditorium, a writer you know strikes up a conversation, thereby establishing the expectation that you will sit together, which is fine, as long as he doesn’t go to the first row, which he does. Now, thanks to the stadium seating, everyone will have a clear view of the top of your head. But it will not be a view of shoe polish because your wife convinced you not to use it on the grounds it would be difficult to remove.

The same effect, she explained, could be achieved with mascara. You don’t know much about mascara, having never worn it before, though you are pretty certain that under certain conditions, such as high humidity, it runs. The auditorium feels like a rain forest. You’re already sweating. You’re already imagining your rectangle of scalp being slowly revealed. You can all but hear the snorts and giggles . . .

For a split second you are back in the barber’s chair staring into a mirror at a man you don’t recognize.Stop obsessing. Distract yourself by perusing the conference’s brochure. The first scheduled reader is the famous writer. You saw him when you entered the auditorium, sitting dead center of the room with a few of his books on the desk before him, colorful Post-its sticking from the pages, and a chill went down your spine. Everyone is eager to hear him, no doubt, but allow yourself to believe he’s eager to hear you.

Why not? Maybe it’s true. Maybe he’s as much of an admirer of your work as you are of his. You’re not famous by a long stretch, but you are, you’ve noticed, last on the schedule, a position, like first, often reserved for a writer of a certain ability, a certain gravitas.

Gravitas indeed! The famous writer brings down the house and leaves the podium to thundering applause. The next reader is outstanding too. As is the next. Everyone is quite good, although, admittedly, it’s difficult to pay close attention while imagining mascara working its way down your head.

Finally, you’re introduced. Go to the podium. Look around the room, really for the first time, and take in the size of the crowd. It’s enormous! Of the hundred or so seats, only a few are empty, one of which, you note, is the famous writer’s. His books are gone too. As indignation bubbles up from some dark place inside you, wonder what’s this guy’s deal, but the real question, you’ve already begun to suspect, is what’s the deal with you.

For a split second you are back in the barber’s chair staring into a mirror at a man you don’t recognize, a man, this time, who’s at an important literary conference with mascara running on his head hoping to impress a famous writer who’s ducked out of the room, failing to find this funny. It’s amazing the difference an ego can make.

Look away from the famous writer’s chair. Greet the audience. Announce that, before you begin, you’d like to take a brief moment, if you could, to talk about your hair. Raise your hands to the heavens. Smile. Now swear, as your beloved grandmother is your witness, that the story you are about to tell is true.

__________________________________

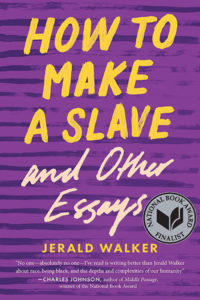

Excerpt from Jerald Walker’s How to Make a Slave and Other Essays, used by permission of Mad Creek Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press.