Jenny Holzer on a Life of Turning Public Spaces Into Art

The Artist Sits Down with Hugo Huerta Marin

For more than forty years, artist Jenny Holzer has presented her astringent ideas, arguments, and sorrows in public places and at international exhibitions. Her medium, whether on a T-shirt, a plaque, or an LED sign, is writing, and the public dimension is integral to the delivery of her work. Throughout her career, Jenny has received several awards, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, the World Economic Forum’s Crystal Award, and the Barnard Medal of Distinction.

A three-and-a-half hour drive from New York City led me to Hoosick, where I met with Jenny on a warm and quiet summer afternoon. We walked around her property until we found a pleasant spot to begin our conversation. For decades, Jenny has projected phrases on to surfaces such as mountains, ocean waves, and rocks. Going outside is her biggest inspiration, so meeting her in this natural context was a privilege for me. Starting in the 1970s with the New York City posters, and continuing through her recent light projections on to landscape and architecture, her practice has challenged ignorance and violence with humor, kindness, and courage. The reigning art world star Jenny Holzer occupies a territory in art that is entirely her own.

*

Hugo Huerta Marin: Let’s start by talking about the strong relationship between the language and the materials that you use in your work: large-scale projections, LED displays, T-shirts, bronze plaques, stone benches, offset posters, and condoms, to name a few. How do you decide which specific material to go for?

Jenny Holzer: Work often starts with the content. Sometimes the text will arrive and it will demand a particular medium. Other times there is a text that is very flexible—even promiscuous—that can live almost anywhere, from a poster to a shirt to a stone bench. The more serious texts seem especially suitable for stone, and when I want to present a high volume of material, an electronic sign with a big brain is a happy home.

“I like to make the floor drop out from under me and everyone else.”

HHM: What role does space play in your work?

JH: I love being an installation artist. I do better when I attempt the whole surroundings. That’s preferable to making one object that’s to be everything. I adore impressive environments.

I like to make the floor drop out from under me and everyone else. I color the air all around—and there needs [to] be meaning in the surroundings.

HHM: I can see that. I’ve always thought that one of your pieces would be fantastic for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.

JH: Yeah, I need an invitation though. It’s preferable not to break in (laughs).

HHM: How does the language change between one viewer and the other?

JH: I try to make language accessible more often than not, because I want the content to land. That said, in a museum I might present more content than I would in the street because I can expect people’s attention spans to be longer indoors. The night-time light projections can have a poetic language, because people may be quieter after dark and more inclined to attend and linger.

HHM: One of the things that came to my attention was the work you’ve done on memorial gardens like the Black Garden of Nordhorn or the Erlauf Peace Monument. When did you first become interested in the concept of memory?

JH: When I was young, I went to a cemetery in my grandparents’ hometown—high on a river bank—and there was a stone bench inscribed with a poem, selected by the poet’s widow to mark his grave. That caught me, because people could pause, look at the broad river, and think of a man and his expression. Because I tend toward bleakness, people began to invite me to make memorials. I had largely stopped writing my own text then, so sometimes I’d use the writing of those who were to be memorialized. Perhaps these people had been murdered or died in some unnecessary way. It was a whole new experience, and a liberating one, to rely on the text of many others.

HHM: It seems that your work sympathizes with victims.

JH: Let’s say I want to keep good people, with their virtues and their utterances, with us.

HHM: To put it better, is spirituality assumed in your work?

JH: Hopefully feeling is. I have a repressed spirituality (laughs). I am not religious in any conventional sense, but I am all for applying appropriate feeling that might make for sanity and better behavior.

HHM: So where does Jenny Holzer end and the formless and indefinable voice begin?

JH: Oh, I’d like to keep myself as far from the voice as possible, because, among other things, it’s freeing, if unhealthy, to be disassociated from it. It’s not an accident that I was an anonymous street artist. When I was a young woman, anonymity let me produce relatively unselfconsciously, and perhaps gave me a bigger voice than I would have had if my work were signed Jenny Holzer—a twenty-something-year-old female artist whom no one had heard of. That signature would have turned the volume down, that was an address for nowhere.

HHM: I also think it’s no coincidence that many people think some of your work was done by a man.

JH: Absolutely.

HHM: Do you think it is because people associate the male voice with authority?

JH: Sure. When I was writing first the Truisms and then the Inflammatory Essays, I explored many different subjects, wrote from multiple points of view, and probably inhabited two, three, or four sexes, and some in between too. If you want to understand people’s motivations, it’s good to indwell as best as you can. Unless they’re a murderer, then it’s best not to follow through (laughs).

“Art can fuse a dreadful or wonderful reality with dreadful or wonderful representation so that people realize and feel what is, and then act.”

HHM: What is your relationship to writing like?

JH: Troubled. Reluctant and frightened, resentful, slow… a lot of sad words like those. That’s the reason it was a tremendous relief to start making memorials with others’ texts, to go to poems for projection, to greatly improve on what I could do solo and to present more than I could generate myself. I’m honored to show text by people who are real writers. Once in a while, as recently for trucks with electronic displays, it’s been possible to compose blasts like “COVID-19 PRESIDENT” or “COVID-19 ECONOMY.” That kind of writing I can muster, to steal what’s now and flash it.

HHM: Do you find there is a difference between writing words that are to be shown and those that are not?

JH: I mostly don’t retain notes. Someone with very good intentions once gave me a number of beautiful diaries to fill in, and in the end I gave them to a poet friend after they sat empty for ten or fifteen years. I desire to be anonymous and largely invisible, so perhaps that influences what I show and what I don’t, what I keep and what I won’t.

HHM: Do you consider yourself a political artist?

JH: I’m an artist, and a person who is political; I make some separation here. I do not represent that art is as straightforward and immediately effective as voting or doing community work, and I don’t think art always can or should be pragmatic and utilitarian. At times, however, art can fuse a dreadful or wonderful reality with dreadful or wonderful representation so that people realize and feel what is, and then act.

__________________________________

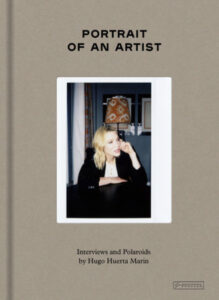

Adapted from Portrait of an Artist: Conversations with Trailblazing Creative Women by Hugo Huerta Marin © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York, 2021.

On October 28, Marina Abramović and Hugo Huerta Marin will sit down for an intimate conversation about creativity, identity, success, and legacy at the global launch of Portrait of an Artist: Conversations with Trailblazing Creative Women at Fotohtafiska New York. Tickets are now available.

Hugo Huerta Marin

Hugo Huerta Marin is a multi-disciplinary artist and graphic designer whose work centers on gender and cultural identity. Since moving to New York in 2012, he has collaborated with cultural institutions in the United States and Mexico, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Hugo works as art director to Marina Abramović, with whom he has collaborated internationally for venues including; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Foundation Beyeler, Basel; and the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Hugo’s solo exhibitions have been featured at The Hole Gallery in New York, Never Apart Gallery in Montreal, and MUAC museum in Mexico City. He was part of the 2019 Casa Nano art residency in Tokyo.