Jennifer Croft on Photography as an Unexpected Writing Tool

“It allows me to reframe the central questions of my work.”

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

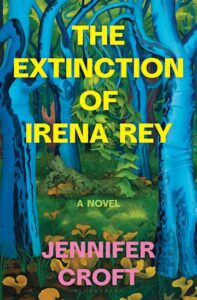

When I get into a writing rut, I like to step back and take inspiration from other art forms, each of which has its own conventions as well as—encoded within those very conventions—all kinds of ways to break with convention and do something fun and new. Perhaps because of its ubiquity, or perhaps just because I love looking at pictures, photography is an art form I turn to often, and I find it nearly always helps: Photography allows me to reevaluate my linguistic and narrative choices from a fresh perspective and reframe the central questions of my work. Sometimes the images become so integral to my story that they actually wind up in its pages, as in my new novel The Extinction of Irena Rey. But images are illuminating regardless of whether your reader sees them or not.

Below are some examples of considerations in photography that can be carried over into literature in myriad productive ways:

Format

Different shapes and structures invite different sets of responses from readers, in the same way a square photo on a cellphone screen will be received and evaluated differently from a 20 X 30-inch matte print.

In prose, short chapters might help maintain momentum; long paragraphs might cause your reader to pause and reflect at a pivotal moment they otherwise might have missed. Lots of white space on the page can open up a text, injecting a little fresh air into moments of darkness, or showcasing positive developments in your plot. I would argue that format in prose also includes decisions like whether to write in present or past tense, first or third person—essential, foundational decisions that are often intuitive at first, but that also often eventually require a more considered working out.

In some ways it might seem easier to play with space in poetry, and there is certainly ample room to arrange and rearrange the material of a poem on the page, but words can be arranged and rearranged in a single sentence to generate all kinds of different effects, and creating interesting syntax is one of the most powerful and underutilized techniques in English-language prose.

Change the order in which a thought is conveyed, and you change the thought itself. Start or end a sentence on a strong word to make the reader pay attention. Slightly unnatural syntax can have the same effect—whenever you defamiliarize language, even if only slightly, readers will take note. (You could also think about this in terms of lenses, if you’re old-school, in which case, adopting a strange syntax might be like putting on a fisheye lens.)

Frame

Will your piece be enhanced by a frame, or an additional frame beyond the margins of the page, and what would that mean in your narration? The classic example of a narrative with a frame is One Thousand and One Nights, but there are so many more: Wuthering Heights, The Princess Bride, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Pale Fire.

Style, and maybe more importantly, whose style?

How much should your subject influence your style? For example, if you’re writing about childhood, should you write like a child? Probably not entirely—but maybe a little? Striking a balance here is crucial, and I always try to think thoroughly about how much of a shadow my own authorial voice is casting over my community of characters, their setting, etc. (That shadow can be thematized, too, of course, just as shadowy self-portraits of photographers crop up every so often in great portraits.)

Contrast

Contrast in sentence length, diction, met expectations vs. unmet expectations may help keep the reader on their toes. (Too much may take them out of the story, just as excessive contrast in photography can feel off-putting or overweening or just gratuitously odd.)

Texture

Sometimes used to refer to sound patterns in a poem, like assonance, consonance, alliteration, texture can also refer to the linguistic features of prose that help shape the reader’s understanding of the story by creating an atmosphere that is particular to your vision and your fictional world.

Depth of field (aka “portrait mode”)

Depth of field is also called “the zone of sharpness.” Deciding on your depth of field means deciding how much environmental context you want to give your reader in your story. You can reduce distraction by blurring or omitting the things that aren’t directly related to your subject. Or you can do the reverse: You can celebrate your subject’s whole vast network by depicting as many connections as you can fit into your frame, creating not so much a portrait as a landscape.

Even more to consider

Try thinking about exposure (brightness), saturation (intensity), grain (the reader’s awareness of your words on the page), the vignette option (Do the edges of the image, or the story, or the poetic reflection darken as a way of helping your reader focus on your central characters, themes, movements?), the circular blur option (same as above, but lighter), or any of the edits you can make to your photographs on your phone. How do you translate shifts like this into your prose?

____________________________________

The Extinction of Irena Rey by Jennifer Croft is available now via Bloomsbury.

Jennifer Croft

Jennifer Croft is the recipient of Fulbright, PEN, and National Endowment for the Arts grants, and her translations from Polish, Spanish, and Ukrainian have appeared in The New York Times, n+1, Electric Literature, BOMB, Guernica, The New Republic and elsewhere. She is a Founding Editor of The Buenos Aires Review. She won a Man Booker International prize for her translation of Olga Tokarczuk. Her memoir, Homesick is now available from Unnamed Press.