Jen Percy Collects the Stories of Love and Sex Addicts While Reflecting On Her Own Romantic Experience

On the Trauma That Can Underpin the Human Need For Connection

In “Persephone the Wanderer,” the poet Louise Glück writes, “Persephone is having sex in hell. / Unlike the rest of us, she doesn’t know / what winter is, only that / she causes it.”

According to Greek mythology, before Persephone was abducted by Hades, she went by the name Kore, which meant “maiden.” She became Persephone only after the abduction—and Persephone means “to bring destruction.”

*

In 2020, Saachi Gupta was living at her parents’ house in Mumbai during the pandemic, and she didn’t leave the house for over a year, not until her friend Nadiya had a birthday party in August 2021. Saachi didn’t want to go because she didn’t want to get COVID, but her friends told her to come anyway. If she didn’t enjoy it, she could leave. She dreaded going and had a breakdown the day before the party. A month earlier, her friend Anika told Saachi that she had feelings for her, and it was confusing for Saachi, because she thought they were just friends.

At Nadiya’s party, Saachi immediately got drunk, and so did Anika. Soon, they were all in the hallway, sitting in a corner together, talking and laughing. When Anika sat next to Saachi, she reached over and quietly squeezed one of Saachi’s breasts, massaging it with her fingers.

“I thought, Holy shit, I have her hands on my tits and not in a good way,” Saachi told me. And Anika whispered, Just say it if you want this. Saachi left and Anika spent the whole night crying and vomiting in the bathroom. Everyone had to take turns taking care of her.

Two days later, Anika texted Saachi, “I was told that I behaved very badly with you, and I just think it would be good for us to take some space.”

Saachi didn’t want to give her space. They had been so close, and she wanted it to stay that way, but she also knew she should give Anika room to deal with whatever it was that had happened. Now, Saachi has panic attacks every time she comes across Anika’s name.

Saachi wouldn’t use the word “assault” because the word is too violent. She kept telling herself it wasn’t sexual harassment; it was just that her boundaries were crossed. Her friends tried to tell her that if it was physical and she was uncomfortable, then it was sexual harassment. When Saachi came across an Instagram post about marital rape, it helped her think of what Anika had done to her as a violation—the same way someone you love and trust in marriage can still make you feel violated.

But there was no safe place to talk about sexual harassment except among the small group of friends and family she trusted. If her extended family knew about it, she wouldn’t feel safe. The politicians in India were vocal about blaming victims for any kind of sexual harassment.

*

Three months later, Anika texted Saachi to let her know she was crying a lot and felt horrible about her behavior, and Saachi realized how much she missed Anika. She woke up for the first time in three months feeling happy again. She was singing in the shower, and she couldn’t think about anything else.

But when Anika and Saachi spoke to each other over the phone on October 17 for three hours, Anika apologized through tears, explaining that she didn’t think they could be friends after what had happened. The violation had changed the way Anika saw herself—she no longer saw herself as a good person. But Saachi thought they still had a chance to save their friendship, and she begged Anika not to block her. She hoped they could still talk or text sometimes. At midnight, they hung up. Right away, Nadiya called Saachi and asked her if she’d spoken to Anika. She said she had. How did Nadiya know?

One can see in Jenna’s story the way love and loneliness can lead us to inescapable places, dangerous places. And that traumas can haunt future desires.

“Anika accused you of making up the whole sexual harassment story and said that you had admitted that it hadn’t really happened,” Nadiya replied.

Saachi checked her text messages. Anika had blocked her. After that, Saachi could no longer fall asleep in her bed, because it was where she used to text Anika all the time at night, and it reminded her too much of what she had lost. She had always felt the safest with Anika. It was different with other friends—if ever she’d had a falling out, she could look back and see the signs—but not with Anika.

Instead, she fell asleep in her sister’s bed, but it was a broken sleep, and she woke up shaking. She skimped on hygiene, no longer brushing her teeth because she just wanted to fall asleep as quickly as possible. In the days that followed, Saachi couldn’t stand being at home, and when she was, she would cry. She started drinking too much and ended up in the hospital. People thought that she should be getting better. And she was doing everything she could to get better. She was in therapy and taking antidepressants and antianxiety pills. Nothing was working because Anika was this person that she never thought she would lose, and now she was gone.

Eventually, Nadiya was cut off, in brutal fashion, by Anika as well, and she went from having a lot of friends to texting Saachi and saying, “I don’t have anyone to talk to.”

A few months later, Nadiya and Saachi went clubbing, and when they got home, they started making out. Saachi had never kissed anyone before, but she wanted to get it out of her system. After that, Saachi started hooking up with random men. She walked right up to them and said, Do you want to hook up? Or she matched with them on Bumble and told them to meet her in two hours. She would hook up with anyone she could find. Sometimes she traveled for two hours just to see someone she had never met before. Mostly she went to their homes, alone. She knew it wasn’t safe, but she did it anyway.

In the beginning, she wouldn’t have sex with them. (She wasn’t comfortable having sex yet because she was a virgin.) But they were often insistent and asked her repeatedly to have sex. Then, finally, she had sex, and after that she had sex all the time. She told her friends that she just didn’t want to be seen as a person anymore—she just wanted to be an object.

“I was a fantasy,” she told me, “like I wanted to become a fantasy for the men, and they could do anything they wanted to me, like tie me up, or fuck me in any way, and I thought I would get some pleasure from the act of sex, but then I was often incredibly bored, and I just looked at things in the room.” She was mostly silent and didn’t enjoy it, but she was also okay with all of it. There was never any attraction, nor any connection. There was nothing. A man tried to get inside her without a condom, even though she told him she wanted him to wear a condom, and he forced himself on her.

On the way home, she looked out the window of the cab and thought, Fuck, I did it again. Why was she setting herself up for more sexual trauma?

She went from being a virgin to having two years of consistently wild and unwanted sex, and she hated every moment of it. She made a list in her notebook, which she still keeps—a list of every man that she’d ever hooked up with. She had slept with thirty-seven people in seven or eight months.

“It’s such a cycle,” she said. “If something bad happens, you either hurt other people or you find ways to hurt yourself.”

She spoke to a therapist about everything that she had done, and the way she had changed, and the therapist told her that “hypersexuality” is not just about having sex, it’s about your entire life—your body language and behavior completely shift. When we spoke, Saachi was still trying to be seen as someone other than the girl who had lots of sex for two years. The year before, for one of her classes, she made a comic strip focusing not on the act of sexual assault but what comes after it, and seeing it play out differently: how it is never perfect and never sweet.

Nadiya had a medical mask that she was wearing when she went to hook up with this guy who ended up sexually assaulting her, and she accidentally left the mask in Saachi’s coat pocket. Saachi keeps it in her coat. She puts her hands in the pocket and feels the mask sometimes. The mask has so much significance for Nadiya, and it’s such a heavy thing to carry around, and it feels good to carry it for her.

*

When Jenna Sorenson turned twenty-two, she decided to move across the state of North Dakota to a town called Spearfish. She and her nine-year-old son moved in with her dad and his wife. Jenna got a job at a tattoo parlor. When she was drawing tattoos, she felt safe from the chattering anxiety that seemed to follow her wherever she went. She was hyperfocused on the drawing and nothing else. Then seeing people’s faces light up after the tattoos—that was a beautiful thing.

After about a week in town, she got a friend request on Facebook from a local man. She accepted his request because he was good-looking, a bodybuilder, and she wanted to make friends. He sent her a message saying he was getting a tattoo from her boss next week and he would be sure to say hi. To Jenna, it seemed the bodybuilder had his life together—he was older, a business owner, and a parent of a little girl. He started bringing Jenna little gifts at work and he’d come see her every day at lunch. That’s just what he did.

On their first day together, he said, “Check this out,” and he showed her a taser and tased himself. Cool, she thought, so the taser doesn’t work on him? It was weird, but she didn’t know if this was a red flag.

She also didn’t think the bodybuilder could hurt her because she’d already been hurt enough.

But any time she was free, he insisted on hanging out. She discovered an audiobook on his phone that was all about how to manipulate people, and he said it was for his business. He said he had two other houses in town, but she’d never seen them. He told her not to wear things with skin showing and not to post anything on social media about the two of them. He took videos of them when they had sex and sometimes she didn’t even know it. She was miserable with him, but she got to meet his mom and his child and his sister, and that felt meaningful enough for her to overlook everything else.

*

When Jenna was in middle school, a lot of guys befriended her because of a rumor another student started about her being easy. Jenna was nice to the boys even after she realized they just wanted sex from her. “But,” Jenna told me, “I just was hoping that one of the boys would actually love me.”

When she got pregnant at fourteen, she didn’t know who the father was because it could have been her boyfriend or it could have been the rapist. The rapist was nineteen, and he had been asking her for photos, asking her to come over. “Being groomed by older men was just a thing,” she explained.

After having the baby, she went to get help at a mental hospital when she was only sixteen because she was nervous and deeply sad and she didn’t want her problems to be her son’s problems. I make friends with other people to get attention, she wrote in her journal at the hospital. I want to be wanted. I want to be valued. I change things about myself to please other people. After forty-five days of medication and therapy she got her mood up and they released her. She still ended up in a lot of abusive relationships after that. “So when it came to red flags and stuff, I didn’t know. I guess at what point do I stop? At what point do I really know? Because it seemed to be that healthy relationships were just a fairy tale. They didn’t exist.”

*

One day in December 2020 the bodybuilder asked if he could sell the videos of them having sex. She said okay and didn’t ask any questions because she didn’t want to seem “crazy,” which is what guys had called her in past relationships when she asked questions. She learned quickly to never push things. Questions meant anger and blame. She was the kind of person who really didn’t speak up. And if she did, it was very brief and sort of quiet, and it really didn’t seem to register with the bodybuilder because somehow the conversation would just wander in some other direction.

The first week they were dating, he wrapped his big hands around her neck and squeezed while he told her how hot she was and how much he liked her. You are beautiful, he said. She thought she was going to die. He said he wanted her to pass out, to lose consciousness, so that she could wake up next to his hard dick, because “that would be so hot.” I’m going to die, she thought. She was sure of it. She hit his arms, but he wouldn’t stop. That was her way of saying she couldn’t breathe. She managed a little squeak, and he warned her not to lose eye contact with him. He wanted that eye contact. To survive, she pretended to pass out, which she assumed had worked because then he let go. But he turned to her and said he knew she was faking it. It was like she had done something wrong.

In the morning, she looked in the mirror and she seemed a bit purple, and there were blue dots all over her face, and one of her eyes was red, not veined red, but solid red, like someone took a paintbrush and swiped red paint over the white. Then the blood started seeping into the other eye. She decided that she had the face of a demon.

Even after all that, Jenna was certain there was something wrong with her because the bodybuilder said, “I strangle other women and they love it.” She wondered if maybe he was just more experienced and that she still had a lot to learn. Maybe it was just something she had to get used to. It took a month for the blood to drain from her eyes.

When she no longer looked like a demon, she spoke up for herself. “You could’ve killed me,” she said.

“That would’ve sucked for you,” the bodybuilder said, “but it would have really sucked for me.”

She tried to tell him that she didn’t want to be with him. She tried saying how she didn’t feel right with him, and that they didn’t have much in common, and that it was okay that they didn’t belong together. But he didn’t seem to hear her when she spoke.

One night he asked her to come over and she said okay, so long as they didn’t have sex. She wanted to sleep and lay down on the bed and try to relax. She had her eyes closed. He came over to the side of the bed. His dick was hard and he shoved it in her mouth. She was crying but said nothing else about it. When it was over, she told him that she was going to go outside for a smoke. She got in her car and left.

It was easier to express herself over text messages. The next day, she told him what he had done. He wrote back: Yeah, I was just being flirty.

Five days later, he asked her to come over again. He needed her ID to get paid for a sex video he’d shot of her. She was afraid that if she didn’t go over he’d come after her for blocking his income. I’m just going to go over there and do this thing, she decided, and then I can be done with him. She stopped by in the morning, about five minutes before work so she had an excuse to leave quickly. He took a photo of her ID and then begged for sex. He took her to the bed and sat her down and undid her pants.

In the past, when he was drunk, he joked about raping her. And when he couldn’t accept that she didn’t want to be with him, he turned his jokes into reality. She didn’t fight. He gave her a vibrator and she just took it and she used it. She wanted to get it over with and the vibrator would put an end to things faster than without one. “I just kind of let it happen, I guess,” she said, not giving herself credit for the things she tried to do to keep herself safe.

“Looking back at this,” she told me, “I just feel so stupid. I regret going over there, and I should have just listened to my instincts, but I don’t know. I guess I was too naive to really understand what was going on.”

When she first met him, she was off all her antidepressants and antianxiety meds, and had been for years, but now she has to get back on them and attend counseling again. If she misses one dose, she has a nightmare. In the nightmare, she’s running from her rapist, although it’s not really him. In fact, it’s not really a specific person: It’s all of the men she has known and thought she loved. In the dream she’s running from them but feels trapped in the movement of the run. She wakes up in the night many times, but every time, when she falls back asleep, she goes right back into the dream. She could even be up for an hour or two before she goes back to sleep, and she’ll still return to the same dream.

She is exhausted when she wakes up.

*

Before the trial, in the summer of 2022, she had been doodling and drawing at home and entered a trance state. She didn’t know what she was making, it just came out: a woman, lying there dead because she got strangled.

Jenna was on the stand from eight thirty in the morning to four thirty in the afternoon. The bodybuilder still had videos that he made of them when they were having sex. The judge decided that it was okay for three of the videos to be played in front of the whole courtroom and in front of the jury. “Those videos had nothing to do with anything,” she told me, “those were consensual.” She admitted to using the vibrator, and the defense argued that it didn’t make sense to use a vibrator and get raped. And so that was that.

“They were trying to say I was lying, and I was doing this for attention. Saying anything that they could to make me seem like I was some drugged-out, crazy, lying, attention whore. I’m being lied to about my own life. They went back and looked at what I wrote when I was sixteen at the mental hospital; how I didn’t have any friends. It was so horrible. They told me I was claiming rape because I didn’t like how I looked in a sex video. But I had never even seen it.” Everything she had ever felt any shame about was on display. “The entire thing was absolutely traumatic. I understand now why people say they don’t want to go forward.”

The court decided that the bodybuilder was not guilty on the charges of strangulation and rape. Jenna came home and fell into a fog. Memories would come back to her in little spurts. She didn’t want to be known for this. She wanted to be known for her art. “And so I’ve been really working on saying what I want to say when I want to say it and not being this scared kitten and just being more dominant, I guess.”

Three months later she joined Brazilian jiujitsu, and it helped her feel more confident—helped her serotonin levels—but there were so many men, and when she tried to practice with men she couldn’t do it because she couldn’t think straight. She just kept imagining them as the bad guys, and she tried to calculate in her head how to escape.

Shame is when you stare at your past self, and she stares right back at you. That’s how I felt hanging out with the love addicts.

Since the tattoo parlor is a few blocks away from the local gym where he works out, she knows he’s often there, and sometimes she even sees him outside. There was one time when she saw him and their eyes locked.

*

One can see in Jenna’s story the way love and loneliness can lead us to inescapable places, dangerous places. And that traumas can haunt future desires.

Mariana Bockarova is a psychologist at the University of Toronto who teaches a course on the psychology of relationships. A lot of the students opened up to her—either in class or later—to let her know they’d been in an abusive relationship or they’d been sexually assaulted and they were taking the class as a way to understand how to build a healthy relationship again. They all felt like they couldn’t have, or didn’t know how to have, healthy relationships with people anymore.

“In the aftermath of such traumas,” Bockarova told me, “it’s really difficult to go back to regulating as a normal person would. You have intrusive thoughts, avoidance, hyperarousal, hyperreactivity, and cognitive distortions—basically to make sure that you’re safe and that you’re in a safe space. If you’ve been hijacked by survival mode—your relationship is with the past more than the person in front of you.”

When I met Mani, a New Yorker in his forties, he told me he had trouble forming relationships and keeping them. And yet, love was all he wanted. “I want a soulmate,” he said.

We first spoke at a Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) meeting on a cold February night at the St. Francis of Assisi Church in Manhattan. The church is an old building with spires and crannies, looking like a candle that’s been left out too long to burn and melt.

I found the “addicts” inside, sitting in a circle of chairs, in a room with nothing on the wall but a small painting of Jesus. The heaters hissed and clanked, let off steam, fogged up the windows. I could guess how tired everyone was by the way they held themselves. They rested their heads in folded arms or stared straight ahead with slack bodies. Some people were still wrapped up in scarves, coats, gloves, keeping themselves cocooned in fabric. Maybe they didn’t want to be seen. It was a Friday, and the most dreaded holiday—Valentine’s Day—was two days away. The city let us know how alone we all were, sending echoes of laughter up from the streets.

I was at this introductory meeting because I was curious to talk to the members. But I also wondered, Was I a love addict? What are they actually talking about when they say “love addict”? I’d always felt like love was the most important thing in the world, all-encompassing. I was a lover of romance. A lover of love. I was drawn to the stories of couples buried in the ashes of Pompeii, two people entwined forever. I had often found myself with men whom I didn’t really know and who were not good matches and did not love me, and I found myself staying with them, waiting for love.

Pamphlets titled Romantic Obsession, Withdrawal, and Healthy Relationships were for sale in plastic bins. An introductory pamphlet warns that in the absence of this 12-step program people will be forced to choose between acute loneliness or addictive relationships, and this will set them up for suicide. I grabbed a quiz for newcomers, which was filled with statements to be agreed or disagreed with: Do you feel that you’re not “really alive” unless you’re with your romantic partner? Do you feel that life would have no meaning without a love relationship? Do you have a pattern of repeating bad relationships? A recovered love addict wearing a beanie and sweatpants dragged a chair into the middle of the room. He was a former alcoholic but said love was harder to quit. Growing up, he had so many dreams; being a sex and love addict wasn’t one of them. He took off his hat and put it back on. The addiction, he remembered, started on Valentine’s Day in elementary school. SLAA states on their website, “First you must face honestly that it is not simply ‘the other person,’ but primarily the neediness inside yourself that is the real source of the terrible pain.” Some people were still madly in love with someone who had rejected them, or someone who had abused them, or someone who hardly knew they existed at all. They were in physical and mental anguish. Letting go of a relationship felt like the world was coming to an end. They dropped out of school, embezzled money. They cut themselves, they overdosed, they abandoned family and friends. One ended up at the ER after an unanswered text. There were people who called their love interest a hundred times a day. Others dropped out of school, betrayed friendships, maxed out credit cards to pay for the relationship, or traveled to dangerous places.

The first meeting had me feeling lonelier than ever, and I tried to leave the moment it ended. But then a man walked up to me. It was Mani.

“Are you new?” he said and brushed his bangs away from his enormous eyes. He had pouty lips and a hairy chest that he let show above an unbuttoned shirt. His pants were tight and his shoes pointy.

“I’m in withdrawal,” he said. He kept his eyes on the ground when he spoke. “I’m not really supposed to be talking to women. I’m not supposed to be making eye contact for more than three seconds with women that I find attractive, and well, I’m breaking that rule right now.”

*

A few months later, Mani showed me the police report where he detailed the abuse he’d endured at the hands of a famous white man. He wrote about the day the man drove him home, parked in his parents’ driveway, and held Mani’s hand in a sensual way; and about the day the man lay naked with him in bed and touched his penis; and about the many nights he invited Mani to a local hotel and abused him. It started when Mani was a teen—the man was in his early forties. Unwanted sexual contact, including rape, went on for years, hundreds of times. Mani suffered while the other man became successful and beloved. It’s because of this abuse that Mani thinks he’s never found love. He suffers from depression, feels shame. Why did this have to happen to him? Can he ever be loved? These are the questions he asks every day.

“Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous is not public enough,” he told me. “People are so into their anonymity that they’re preventing others from getting the help they need. These are intimacy disorders. The number one characteristic of a sex and love addict is getting involved with someone without knowing them.”

*

On good days, Mani meditated, drank water, tidied his apartment, and listened to monk sermons. On bad days, he messaged fantasy women. His fantasies were the opposite of what he wanted in real life. In fact, he told me, “They are nightmares that turn me on.” He had trouble getting work done because he just wanted to be in the fantasies all the time. “I’m talking to these women because I’m fantasizing about them,” he explained. “I’m also talking to these women because they’re far away. The women here, I might actually have to be their boyfriend. It’s like I kind of want something more distant. It’s a poor substitute for real love.”

Sometimes he wrote down regrets in his notebook. Masturbation without love, he wrote. Orgasm without love. Premature sex. Sex before she’s really your girlfriend.

SLAA gave Mani rules to live by. He wasn’t allowed to look at women he found attractive for more than three seconds. He wasn’t allowed to look at Facebook photos of a particular model he met on the subway. He was allowed to talk but not flirt with bank tellers, baristas, and store clerks. “They call it sobriety,” he said, “but it’s celibacy. It’s emotional and physical anguish.”

The withdrawal from fantasy can be bodily, full of aches and illness, followed by thoughts of rage, suicide, new addictions, and despair. It’s usually when people fall apart.

“I had withdrawals from females much worse than any withdrawal from alcohol or drugs,” one of the members told me.

“Grieve like they are dead,” a sponsor recommended. “It is not a separation, it is a death.”

*

Mani tried not to talk to women from nine to five on weekdays. “Red-zone time,” he called it.

When his therapist gave Mani the green light to date again, Mani showed him the profiles of the women he wanted to contact on OkCupid. They were all women doing headstands in leotards, whom the therapist called “narcissistic fantasy women who would never love him.” Mani was impressed that his therapist could know this just by looking at the photos.

To show me how bad things were going, Mani played me a voice recording of one of his therapy sessions.

“They are rejecting you,” the therapist said, “and that excites you. And that’s perverse.”

“I could fall in love with them,” Mani said, “do all of this work, and then they could die.”

“You are waiting for love,” the therapist told him, “because you are afraid of it, and you are getting lonelier and sadder.”

*

“You can tell my story,” a love addict named Destiny said. “I kind of want to be famous, and we really need the publicity. No one even knows about us.” Destiny is a twenty-something love addict with dark curly hair and big glasses whom I met at a meeting called “How to Become Unaddicted to a Person.” She tried to leave her abusive boyfriend six times, but they always ended up back together. He insulted her, locked her up, slapped her. “On the one hand I was thinking, This is horrible,” she said. “On the other hand I liked that this person was pining over me.”

They dated for seven months—the longest she had ever been in a relationship. The whole time, he insulted Destiny, telling her things like how her hair smelled like Play-Doh or saying “Having sex with you on top is hard since I usually do this with small women.” He always talked about his ex-girlfriends. If she tried to leave, he’d lock the door and stand in front of it. She couldn’t say no to him. She would always see him even when she didn’t want to see him. She cheated on him, hoping he’d leave her, but he didn’t. The abuse escalated. Destiny told me she had always had trouble understanding the difference between being sexually attracted to someone and loving them. And she would make herself think she was attracted to someone just because they were attracted to her. Then, as soon as a kiss would happen and “their teeth clinked,” she would stop herself and think, What am I doing?! There were a lot of guys in college she tried to make her boyfriend. She loved the attention. But part of her was afraid of intimacy. None of the men she dated were emotionally or even physically available. She had lost her virginity to someone in a foreign country and was devastated when he broke up with her a month early, even though they were going to break up a month later anyway. “And then once I dated a man who was very weird. I had this fantasy that he was this brilliant writer and I was his muse. Well, that wasn’t true. Fast-forward to being in New York and trying to find love. I’m just not hot enough.” When she finally thought she had the strength to leave her depressed and abusive boyfriend of seven months, it was almost like he sensed it, and he was at her apartment waiting for her. He said he wanted to break her nose, and then he slapped her. She ran away—out the door and onto the street. She caught a cab and told the driver to take her directly to an SLAA meeting. They told her that her case was extreme, and she should check herself into a trauma treatment facility in New York. She needed locked doors and security to stay away from the abusive man she loved. She stayed for ten days. That was the beginning of what she calls “no contact.”

“If I didn’t do anything,” Destiny admitted, “this would be my entire life.”

*

Meg is a comedian in Los Angeles, and for years all she did was cry, talk about men, and fail in her relationships. Men would tell her that they didn’t want a serious relationship and she would stay with them anyway, holding out hope that they were the one, because they were just so magical. Meg told me about the time she was dumped but didn’t accept the reality of it. Her first thought was: You are going to see me. She hung up the phone and ran into the middle of traffic on Sunset Boulevard to try to catch a taxi. She didn’t want to waste time, so she stepped in front of a moving taxi, and it stopped just before it hit her. She was a little bruised and scratched up when the cab dropped her off outside the man’s house. She was drunk and covered in blood, and he did not take her back.

When she wouldn’t stop crying, a friend in Alcoholics Anonymous told her she might want to join Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous. Meg had never heard of it, and she wasn’t excited about it. At the time, she was having an affair with a married man, dating multiple people on Tinder, and thinking she was in love with a guy friend. She weighed ninety-three pounds and was completely out of her mind attached to another person. She imagined everyone at the meeting was going to be a pervert, but she was desperate and went anyway.

Maybe because of the power some people inherit, they feel a need to engage, and so people like myself forgo our own comfort to comfort them. It’s how many girls are raised, and how I was raised.

The meeting was in a drab room in a church. Everyone said their name along with their affliction. There seemed to be so many afflictions: love addicts, sex addicts, romantic obsessives, intimacy addicts, fantasy addicts, emotional anorexics, intimacy anorexics. Meg didn’t know what she wanted to call herself and so she said, “I’m Meg. I’m new.” When the meeting was over, she left without talking to anyone. She wasn’t taking it seriously—she kept drinking and dating men who treated her badly. She started hooking up with a guy she met in the comedy scene. He was a recovering sex addict, and one morning she woke up on his floor after falling unconscious from too much drinking, and that’s when she decided to get serious about the program.

She preferred the women-only meetings. It was usually a group of fifteen to thirty people crammed into a room at a church. Meg noticed that most people at the meetings introduced themselves as sex and love addicts, but she didn’t really relate to the sex part. A year passed before Meg introduced herself as both a sex and love addict.

“I still don’t totally relate to the sex addiction,” she told me. “But I confuse sex with love, and love with sex. So I’m a love addict who uses sex to get love.”

She was paired with a sponsor, an experienced member who guided her through a recovery plan. And as part of this plan, Meg was told to avoid contact with men for ninety days, especially men who were ex-boyfriends, men she found attractive, and men she’d been involved with in the past. It also meant no conversations with any man for more than two minutes, and during those two minutes she wasn’t supposed to reveal any personal information. Meg also stopped going on dates. As she made her way through the program, an acquaintance asked her out on a date. Meg liked him but had to tell him she was unavailable until she finished the 12-step program. If men reached out to her, she ignored them or explained to them that she was in a recovery program. They’d have to wait.

“It was brutal,” she told me. “It was really painful. I was afraid men weren’t going to like me anymore.”

The acquaintance waited eighteen months. They started with one coffee date a week, and after a couple of months, two dates a week. She didn’t let him come into her apartment until they were a couple. They didn’t have sex until they decided they loved each other. The first time I spoke to Meg, they were moving in together. The second time I spoke to Meg, they were planning a wedding.

“Sadly,” she told me, “it’s part of our culture. You think you’re supposed to be hooking up with people all the time. You hear: Just hook up with him! It’s not a big deal! But for me, it ate my soul away. I didn’t actually want to be doing that.”

*

“You know romantic movies, romantic comedies?” Andrea Owen, a former love addict turned life coach, told me. “Well, that’s our real life. We believe in falling madly in love on the first date and in love at first sight. If we have an amazing first date, then we become obsessed with that person. You know when you break up and you are sad because you are alone? Well, for a love addict it’s about ten thousand times that.”

She stayed with her ex through rumors of affairs and long nights where she didn’t know his whereabouts. She wanted to leave him, but she couldn’t do it. When she was thirty-one, he impregnated their neighbor.

After the divorce, she had a lot of trouble meeting men who cared for her. She dated a man who lied about having cancer to cover up an addiction to opioids. She dated abusive men over and over.

Abuse, neglect, or drama—it was all mistaken for intimacy.

*

I felt an affinity with this kind of longing.

I remember dating one person after another for many years without really knowing them, and then being devastated when things ended.

Friends had often asked, “Why do you keep dating these people who don’t care about you?” But also, “Why do you date people you don’t even seem to like?” Those people were proxies of companionship, salves for loneliness. I was a woman who could sustain a fantasy of goodness or compatibility or connection.

I stayed with a man who lived on another continent, and even though I rarely saw him, I spent thousands of dollars I did not have to fly across the Atlantic to see him, even after finding his backpack filled with condoms.

I stayed with the man who lied about being addicted to drugs and who vanished for weeks at a time and who snorted so much cocaine that blood leaked out of his nose like a fountain and splattered all over my face. He talked of ex-girlfriends and ex-ex-ex-ex-girlfriends and there seemed to be so many of them. The relationship was sustained by drugs and drinking and there were great voids of time spent together, talking about things I will never be able to remember.

I stayed with a man my friends said was always yelling at me, but I didn’t remember him yelling. Maybe I disconnected from those moments.

I stayed with the man who announced to me that everything around him was always self-destructing. And when I was with him at the airport the parking ticket machine broke, and at home the sewage pipe broke and filled the basement with shit. He had been to war and was obsessed with war. I was so broke that I took out a $250 loan from the bank just to go skydiving with him, even though I don’t like planes and I don’t like skydiving. I just hoped the skydiving would bring us together.

The critic Helen Lynd once wrote, “The exposure to oneself is at the heart of shame.” Exposure not only of oneself to another person but to a self that you hadn’t yet recognized—or else ignored. We assume that we are one kind of person living in the world, until we discover we are something else altogether. Shame is when you stare at your past self, and she stares right back at you. That’s how I felt hanging out with the love addicts.

*

The scholar Lauren Berlant has written that “to intimate is to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures,” but must also involve “an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about both oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way.” Sometimes we think people are connecting to us on a much deeper level than they actually are.

In past relationships, I’d always felt a bit like I was narrating the space between us, forgetting about myself, about my thoughts—that I even had them. Maybe because of the power some people inherit, they feel a need to engage, and so people like myself forgo our own comfort to comfort them. It’s how many girls are raised, and how I was raised.

Berlant’s intimacy describes a call-and-response—a way of being in a healthy relationship that I began to know only after I met my husband. It was such a simple thing. If I needed something, he gave it. If I was hurt, he attended to it. If he held my hand, I squeezed back. Our lives and bodies conversed and chattered. We shared a story, and until I met him, I had never had a story that was shared.

*

On a spring day in Midtown in 2018, I met Mani at a vegan restaurant. His beard was shaved, but a long, drooping mustache remained. He was dating again, he told me, “sober dating,” under the supervision of his psychiatrist.

“Do you think you actually want to be in a relationship?” I asked.

“Yeah. I want a soulmate. I’m at the age now where I’m very sensitive. I have nineteen ex-girlfriends. I forget how many of those lasted a year, but that’s the average length.”

We were meeting his friend Scarlett, a woman he met at a party; they’d discovered right away they were both love addicts.

“We had vegan lunch yesterday, but she needed to go home to print something and needed my help and so I went home.”

__________________________________

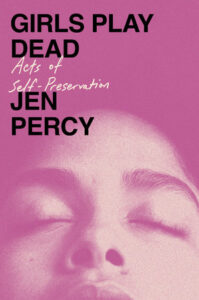

From Girls Play Dead: Acts of Self-Preservation by Jen Percy. Copyright © 2025. Available from Doubleday, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Jen Percy

Jen Percy is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine and recipient of the National Magazine Award for Feature Writing. She is the author of the nonfiction book Demon Camp, which was a New York Times Notable Book. Percy has received numerous awards including a Pushcart Prize, the National Endowment for the Arts grant, and fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the MacDowell Colony. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Percy has published essays in the New York Times Magazine, The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Harper’s, BookForum, The New Republic, Esquire, and elsewhere. She teaches writing at Columbia University.