Greek [Grec]! The dry elegance of this word, its brevity, its rupture even, a little abrupt, are the qualities that can be readily applied to Jean Cocteau. The word is already a fastidious work of cutting: thus it designates the poet freed, cut loose from a substance whose chips he has made vanish. The poet—or his work, but even so, it is still he—remains a curious fragment, brief, hard, blazing, comically incomplete—like the word “Greek”—and one that contains the virtues that I want to enumerate.

Luminosity above all. An illumination, above all uniform and cruel, showing precisely the details of a landscape apparently without mystery: that is Hellenic Classicism. The intelligence of the poet, in fact, illumines his work with such a white, raw light that it seems cold. This work is elegantly disordered, but each of its shafts or plinths was rigorously worked over, only, it seems, to be broken and left there. Today, beautiful foreigners visit it. It bathes in a very pure, very blue atmosphere.

It is not just playfulness that makes us, in speaking of Jean Cocteau, develop a metaphor. The word “Greek” was chosen by him, and he often sought to illustrate or refer to Greece as a whole. That is because he knows the darkest, most subterranean, wildest, almost insane aspects of what it signifies. From Opéra to Renaud et Armide, we guess these columns and broken temples to be the visible form of a pain and despair that chose—not to express themselves—but to hide themselves, by fertilizing it, beneath a gracious appearance, one that is a little mundane, since it seems understood that the noble collapse of Hellas belongs to a frivolous world.

That is the tragedy of the poet. A deep human humus, almost foul-smelling, exhales whiffs of heat that sometimes make us red with shame. A sentence, a verse, a drawing of a very pure, almost innocent line in the interstices between words, at the point of intersection, emit like smoke a heavy, almost fetid air, revealing an intense subterranean life.

That is how Jean Cocteau’s work seems to us, like a light, aerial, stormy civilization hanging from the heavy heart of our own. The very person of the poet adds to it, thin, knotted, silvery as olive trees.

But to have borrowed such forms was dangerous, for the least-developed minds came up with the notion of pastiche; while others even worse, gravely pondered this elegance alone and not what summoned it. So today, here, we want to draw your attention not to the way in which the poet hides himself, but to what it is he seeks to hide. Poems, essays, novels, theater—the entire body of work cracks, and lets anguish be discovered in the fissures. A vastly complex and sorrowful heart wants both to hide and to blossom.

Jean Cocteau never gives us shameless lessons on morality—if he had to advise us, perhaps it would be with a malicious smile.

Is it a profound intelligence that makes this work infinitely sad? It trembles. We know that our images aren’t very precise, but when expressions like “heavy chagrin,” “profound despair,” “wounded heart” are uttered, what remains to be said? As soon as we see a man’s pained face—sternly in command of his pain, managing to transform it harmoniously—how can one speak with precision without a wounding pedantry?

Jean Cocteau? He is a very great poet, linked to other poets by the brotherhood of the brow, and to men by the heart. We again insist on that, for it seems that a deplorable misunderstanding has developed about it. The grace of his style had to become the prey of what the world thinks of as the basest thing: the elite.

Which wanted to monopolize, make its own, this elegant form, neglecting the delicate bitter almond it contains. This time, though, we violently refuse this compromise and come to claim our rights over a poet who is not light, but serious. We deny Jean Cocteau the stupid title of “enchanter”: we declare him “enchanted.” He does not charm: he is “charmed.” He is not a witch, he is “bewitched.” And these words do not serve just to counter the base frivolity of a certain world: I claim that they better express the true drama of the poet.

Others besides me, cleverer, more learned, will speak to you of Jean Cocteau’s place in literature, of his influence on Letters and on several generations, of his style and of the transparency of his poetry; as for me, I am concerned only with his heart, cultivated according to a rigorous morality and producing that rare plant: goodness. You understand: I am speaking of the quality that is more intelligence than sensibility, that is extreme comprehension.

It was no doubt pursued and attained at the same time as the perfection of style that testifies to it. I call on you to try to find, word by word, line after line, the severe—parallel—progression of the purity of the writing and of moral honesty. Jean Cocteau never gives us shameless lessons on morality—if he had to advise us, perhaps it would be with a malicious smile, the opposite of morality, but his sentence is constructed with such a respect for verbal substance that this attitude, which is presence of mind, remains every time.

It is then the rarely faltering rigor of a way of life that I invite you to discern in this style. Lightness, grace, elegance are qualities that refuse laziness and weakness, but what would they be if they were not applied to the hardest materials? But unlike the workman who, out of preference, chooses marble, the poet, by the choice of his method and his words, creates marble. Earlier we spoke of Greece. You will understand now: it was a matter of this new marble: the moral idea we shape from it.

__________________________________

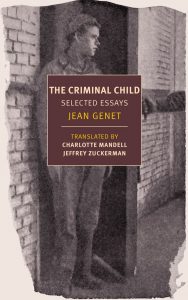

From The Criminal Child: Selected Essays. Published in English by NYRB Classics. Essay copyright © 1950 by the Estate of Jean Genet. Translation copyright © 2003 by Charlotte Mandell. All rights reserved.

Jean Genet

Between 1944 and 1948, Jean Genet wrote four novels—Our Lady of the Flowers, Miracle of the Rose, Funeral Rites, and Querelle—and the scandalizing memoir A Thief’s Journal. Throughout the 1950s he devoted himself to theater, writing the boldly experimental and increasingly political plays The Balcony, The Blacks, and The Screens. After a silence of some twenty years, Genet began his last book, Prisoner of Love (available as an NYRB Classic), in 1983. It was completed just before he died.