Jane Jacobs on Civil Disobedience and the Necessity of Resistance

"Civil disobedience is an extension of self-government."

Correspondence with the New York Times Magazine, November 1, 1967, unpublished.

An act of civil disobedience is justified—in fact becomes necessary—when an individual makes the following judgements: his government is behaving wickedly or stupidly beyond the bounds of what he perceives as tolerable; dissent, having been earnestly tried, has proved of no avail; selective resistance to the law is preferable to various slyer or more violent alternatives.

These are subjective judgments, as all decisions based on conscience must be subjective. If war is an extension of diplomacy, civil disobedience is an extension of self-government. [1]

Vietnam demands disobedience. However plausible or implausible our presence there may have been, however rational or irrational for us to have tried to “fight Communism” there, the fact is that we lost. We defeated neither the Viet Cong nor, subsequently, Hanoi, sufficiently rapidly and with sufficient Vietnamese support to permit us to proceed with effective political and economic programs; our chances of doing so are gone.

Having lost the war, we have proceeded for the past two-and-a-half years to engage instead in an enterprise sicker and uglier than war itself: an enterprise of slaughtering, starving, destroying and uprooting, to no purpose except to postpone acknowledging failure. This is now the only point of our presence in Vietnam. Dissent has clearly been useless in deterring this monstrous exercise.

Because the whole enterprise feeds directly and insatiably upon the bodies of our own young men, as well as upon Vietnamese, it is directly vulnerable to acts of resistance against the draft. The burden of resistance by disobedience thus falls disproportionately upon young men for a wholly practical reason. But practical disobedience is not limited to draft law resistance; we have yet to see what its limits are: they will be determined only by the ingenuity with which people discover ways to interfere concretely in the schemes of the authorities.

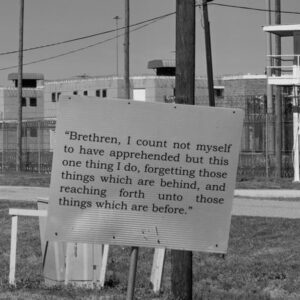

To be sure, not all civil disobedience consists of practical obstruction. Some is symbolic. Practical acts like draft resistance begin as symbolic acts of resistance; there is overlapping. The uttermost limit of symbolic resistance to the law is death, as in the cases of Buddhist monks and others who have set themselves afire or as in some instances of fasting. [2]

Merely by happening, civil disobedience affirms that outside the corridors of power are men and women who make judgments, possess courage, form intentions, captain their souls, and act on their own. To those who habitually (often unconsciously) regard most other people as objects to be manipulated or ignored, the evidence of self-propelling integrity out there seems to translate to anarchy, hence is appalling. That, I think, is precisely why innocuous acts of symbolic disobedience—crossing a line at the Pentagon, say—are described as loathsome and why the perpetrators of acts so innocuous are beaten so brutally. [3]

* * * *

1. With this phrase, Jacobs is referencing Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), a Prussian general and writer on military matters. Known for his realist tack, which Jacobs likely appreciated, his contention in the posthumously published On War (1832) that “war is an extension of diplomacy” is his most famous contribution to the theory of warfare.

2. In June 1963 in Saigon, South Vietnam, a Buddhist monk, Quang Duc, burned himself to death to protest the American-backed government of Ngo Dinh Diem, which persecuted Buddhists. Over the next few months several other monks in South Vietnam followed suit. In the coming years a handful of Americans would immolate themselves to protest US involvement in Vietnam, most famously the Quaker Norman Morrison, who in 1965 set himself afire outside the Pentagon just under the office window of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.The tactic lives on today, too, as in the case of Mohamed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor whose self-immolation in late 2010 was widely heralded as having touched off the Arab Spring.

3. This was the famous march on the Pentagon on October 21, 1967. Jacobs was arrested, along with 650 others.

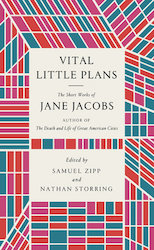

From Vital Little Plans: The Short Works of Jane Jacobs, ed. Samuel Zipp and Nathan Storring. Used with permission of Random House. Copyright © 2016 by The Estate of Jane Jacobs.

Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs (1916–2006) was a writer who for more than forty years championed innovative, community-based approaches to urban planning. Her 1961 treatise The Death and Life of Great American Cities became perhaps the most influential text about the inner workings and failings of cities, inspiring generations of planners and activists.