Jane Austen, Gritty Educational Reformer of the Working Class

Janine Barchas on How the Proliferation of Penny Editions

Brought Literature to the Masses

From about 1890 to 1940, a half century of ultra-cheap editions of Jane Austen’s novels aimed explicitly at educating the working poor. Because these ill-printed and shabby versions of her stories never made it into the scholarly libraries that safeguard “important” editions, the hardscrabble category of her reprintings has remained invisible to modern historians and literary scholars.

However, during ten years of unconventional book hunting outside of academic libraries, I unearthed a host of unsung and unrecorded Austen editions that originally sold not in posh bookshops but at railway stations and downmarket stalls for rock-bottom prices. By the late 19th century, technologies such as stereotyping and pulp paper had lowered production costs so dramatically that book prices allowed for ownership among the working classes, garnering new audiences for Austen.

All of us know that library shelves are not neutral depositories of knowledge—but did we realize that the prides and prejudices of collecting practices were, by neglecting the cheapest books at the bottom end of the market, culling the ordinary reader from reception histories? History has been remarkably unfair to the very books that did much of the heavy lifting of raising Austen into the literary canon.

Grand visions of canon formation aside, cheap editions of Austen push educational utility, social aspiration, and domestic relationships.

Plain Janes of social reform have gone unnoticed and uncollected due to their intolerable cheapness and low production values. In spite of their dull appearance, however, economy editions of Austen were ablaze with social idealism. Cheap books democratized reading and spread her work which in turn helped make Austen canonical.

Austen’s stories often feature heroines fending off genteel poverty or suffering the injustices of inheritance law. In coarse versions such predicaments read differently than in so-called fine editions. This is not because these lowbrow books altered or edited her original plots but because they reached a different reader—a new working-class reader earning perhaps only a pound a week. Since Elizabeth and Jane Bennet in Pride and Prejudice are entitled only to 40 to 50 pounds per annum after their father dies, the economics of their situation might have spoken to just such a reader, for whom a Mr. Bingley with “four or five thousand a year” was indeed a fairy-tale prince.

Proud signatures surviving in even the most modest Victorian reprints of Austen confirm not only that book ownership was itself becoming an aspirational activity for the working classes but that Austen was avidly read by men as well as women. In the 1890s, how did the Staffordshire coal miners and potters proudly sharing a copy of Mansfield Park in a Sunday temperance society relate to the rags to riches story of Fanny Price? Grand visions of canon formation aside, cheap editions of Austen push educational utility, social aspiration, and domestic relationships.

But just as elite critics differ in their interpretations of Austen, working-class readers were not monolithic. Even at the lowest price points Austen comes packaged in mercurial ways—contemporary and traditional, tawdry and wholesome. Some late-19th-century publishers front cheap Austen reprints with sensational illustrations: during the 1890s, Brandon and Willoughby duel with pistols on a sixpenny reprint of Sense and Sensibility while Lydia flirts among soldiers at Brighton on the cover of a shilling copy of Pride and Prejudice. At the same time, Austen’s stories are marketed as Victorian schmaltz alongside cheap religious self-help tracts, with saccharine illustrations and decorative frill. The People’s Jane is just as diverse as the highbrow Jane of precious editions.

Both Stead and Newnes chose Austen specifically for her accessibility to the working poor (think “relatable”).

Austen first emerged in penny editions in the 1890s. Penny versions were modeled on the sensational Penny Dreadfuls, those cheap stories of violence on which Britain’s lawmakers were known to blame the rise in urban crime. Operating in tandem, two newspaper giants stepped in to offer better entertainment to “the poorer millions.” These alternatives were pushed as “Penny Delightfuls.” William Thomas Stead boiled down Pride and Prejudice for an abridgment at a mere penny, while George Newnes printed in two penny parts the complete and unedited text of Sense and Sensibility—its miniscule type requiring good eyesight.

Physically, the penny editions were ugly little ducklings. Roughly stapled and glued, each unadorned text was printed tightly on cheap paper, resulting in a book that was barely larger than a small modern paperback and a lot thinner, with advertisements, inside and out, to subsidize printing costs.

Having died in 1817, Austen was long out of copyright by the 1890s and low-hanging fruit for reprinting. But—and this may surprise modern readers who think of her as a member of the elite—both Stead and Newnes chose Austen specifically for her accessibility to the working poor (think “relatable”). The preface to the Penny Library edition of Sense and Sensibility insists that “her characters are every-day characters and her incidents every-day incidents.” At a time when Austen was just being accepted into the canon by critics, these two editors presented Austen as an accessible recorder of the domestic commonplace rather than as a novitiate of the literary elite.

Keen to enable a “Reading Revival” among the working poor, Stead and Newnes argued that it was the civic duty of publishers to lower the cost of good and entertaining books (they did prize Austen’s humor). Their experiments spurred others, with the result that penny classics became, at the dawn of the 20th century, briefly the order of the day. Despite the explosive success of the penny novel, most were read to bits and thrown out as ephemera.

Take Austen’s share of Stead’s Penny Novels, the 58-page digest of Pride and Prejudice, which came to roughly 100,000 copies. Globally, less than a handful are recorded as surviving in scholarly libraries, making this ultra-cheap version, ironically, far rarer now than surviving copies of the novel’s precious first edition, estimated to have amounted to a run of possibly just 750 copies.

Although missing from the historical record, cheap reprints made Jane Austen a go-to-author for those with small budgets and big educational ambitions in 20th-century America. The Depression slowed down book production and raised prices but the cautious and conservative decade of the 1930s witnessed an uptick in self-improvement books, in anthologies such as Reader’s Digest, and in subscriptions to book clubs—although clubs involved fees and favored expensive hardbacks. Cheap do-it-yourself educational kits sprung up, with Jane Austen in tow.

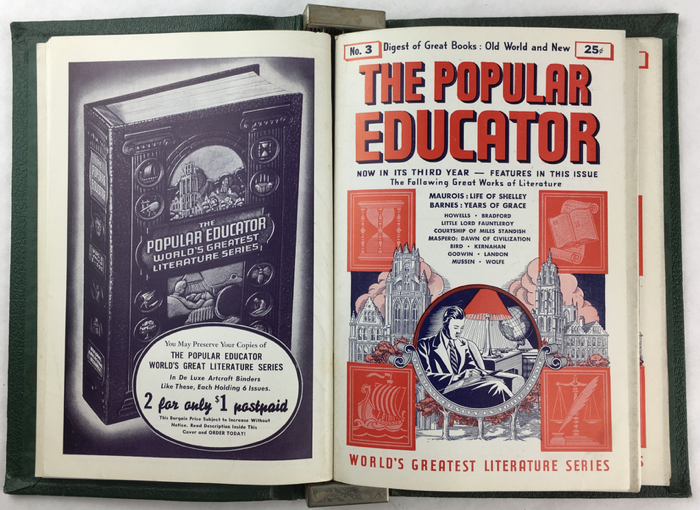

In 1938, one weekly directed at the committed self-taught was “The Popular Educator,” billed as “the university in your home.” Published by the National Educational Alliance, these 25-cent pamphlets for autodidacts (which exploited the second-class postage for magazines) had to be gathered into special binders by the subscriber to make a complete book. The striking “Artcraft Binders” each held six continuously-paginated issues of, at first, university-level lectures on different topics and, eventually, extracts from “Great Works of Literature.” With covers suggestive of industrial manuals, these volumes educated at a bargain price, building a flashy-looking library for home-schooling adults.

Drawing first from Pride and Prejudice in 1939 and soon from Austen’s other works, this series offered a seven-page digest of Persuasion, creatively subtitling it the Story of an English Narcissus (volume one of 1940 pictured above). Short extracts from the novel were stitched together by three startling section headers: “The Vain Baronet of Kellynch Hall,” “Love-making at Lyme Regis,” and “Love Triumphant.” In spite of the inevitable butchering of Austen’s prose and story, the leatherette embossed binder proudly presents Austen with the disarming heraldry befitting university branding. Was this Austen playing her role in the American dream—as an author who might improve a reader’s lot through industry and education?

In 1939, when unemployment in the United States still lingered dangerously close to 20%, those without jobs sought education as a way to get back into the market. Publishers reached for Austen once again. For around a dollar per set, Appleby & Company promised an instant university education with a select set of titles packaged in a plain cardboard box. Appleby’s inexpensive boxed sets courted readers who had missed out on a traditional college classroom and for whom hardback books remained prohibitively expensive.

Was this Austen playing her role in the American dream—as an author who might improve a reader’s lot through industry and education?

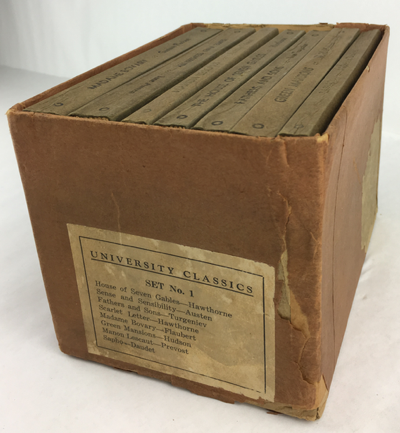

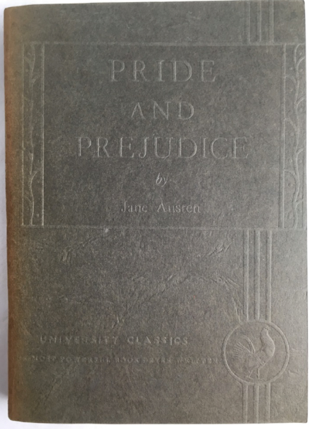

The Appleby paperbacks mimicked the bare-bone penny novels of the 1890s in aesthetics and pedagogical intent. Their self-study paperbacks of “the most powerful books ever written” were sold as “University Classics,” with the first kit consisting of eight novelists among whom Austen was the only woman and the sole Brit: House of Seven Gables by Hawthorne; Sense and Sensibility by Austen; Fathers and Sons by Turgeniev; Scarlet Letter by Hawthorne; Madame Bovary by Flaubert; Green Mansions by Hudson; Manon Lescaut by Prevost; and Sapho by Daudet.

The books look just as drab and serious as may be. Although the print is clear and easy to read, the paper is rough to the touch and quick to brown. The volumes are devoid of graphic flourishes and glued into covers of dark grey thick paper, embossed rather than printed, with raised text that can only be read in raked light. For what amounts to only $1.75 per volume in today’s currency, buyers had to see beyond Appleby’s low production values. The message is clear: in this box you will find a no-frills education whose quality lies in the wisdom of the texts themselves. There are no editorial interventions—no notes and no fussy explanatory introductions. The stubborn independence and austerity of the packaging insists that authors are their own best teachers. This is Sense and Sensibility as masterclass for the working man and woman!

Austen shone particularly brightly for Appleby readers eager to catch up to the education they missed. Pride and Prejudice, available by itself around 10 cents, was part of a second Appleby box. As I was able to trace only 25 total Appleby titles, the doubling down on Austen in such a compact series suggests not merely her growing importance to college curricula generally but confirms her standout role in the education of the working-class student. The Appleby project, too, has unfortunately left little trace, with no entries in Austen’s official bibliography and remarkably few surviving copies in academic libraries.

Scholars study editions, while readers read books. Low-born books seldom join the shelves of elite libraries and so cheap books live the hard lives for which they were destined. They pop up and then they disappear. But shouldn’t historians of reading know about all the versions in which an author was encountered? Inauthentic and ugly reprints, warts and all, were the versions of Jane Austen that reached ordinary working folk. Over the years, Austen’s reception history has effectively been sanitized; it failed to record or preserve the versions with, quite often, the greatest number of readers. But now it is time to democratize and enliven this history with the books that, after trying to help readers overcome adversity, have themselves suffered undue neglect.

——————————————

Janine Barchas’s book The Lost Books of Jane Austen is now out from Johns Hopkins Press.

Janine Barchas

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor of English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity and Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. She is also the creator behind What Jane Saw (www.whatjanesaw.org).