It’s Taken 40 Years For Me to Write About the Day My Brother Died

Richard Beard on a Family's Denial and the Fragments of Memory

Most days, on holiday in Cornwall, the family walks to the beach. A path drops steeply, and either side wheatlike heads of wild grass grow at waist height. Some of the seeds strip away neatly between childish fingers, and some do not. Each time I scatter a pinch of seeds into the greenery, I win. I made the right choice, and at the age of 11 it feels important to be right, or lucky.

We are a family from Swindon, England, on our summer holiday to the seaside. In 1978 this is what landlocked families do: spend a high-season fortnight on the coast, in Wales or Cornwall, in search of quality time that later looks bright and simple in photographs.

The family is Mum, Dad, and four boys. I am second in a declension that goes 13, 11, 9, 6. My brother Nicholas Beard is 9. For nearly 40 years I haven’t said his name, but in writing I immediately slip into the present tense, as if he’s here, he’s back. Writing can bring him to life.

On the sand at the wide Cornish beach we set up camp. Mum lays out a blanket, while we tip plastic buckets and spades from a canvas bag. We take off our trainers, stuff socks inside. The picnic is in a wicker basket, and hopefully today’s Tupperware contains hard-boiled eggs, my favorite.

The beach is huge, the sand compacted and brown. We sprint up and down, leaving crisply indented footprints, evidence that we exist with boyish mass and acceleration here, now, or verifiably just moments ago. Every year, wherever the holiday, we run faster—the prints lengthen and deepen, rows of four in races for a made-up podium.

In the sea, we jump the waves. Look, look out, here comes another. We cherish our special knowledge that every seventh wave will be bigger. We swear by our one and only fact about the rhythms of the sea, but rarely count to seven to check it’s true. Some waves are suddenly huge, not thigh- or waist-height, but up to the chest, the neck. These are the best of waves, sent from the mysterious deep to amuse us. We don’t go out farther than we can stand, and we’re not interested in swimming. The fun is in the contest against wave after wave, whatever the Atlantic’s got; we tumble for ages like apes, never feeling the cold.

At some point we’ll dry off and try a game of cricket, but coastal winds blow the ball off-line and the bounce on sand is variable. The cricket never really takes because Dad wants everyone to bat, as if life is fair. He doesn’t understand that we’re in it to win it.

What do I know? I mean what I remember, what I carry with me.

My brother Nicholas Beard is 9. For nearly 40 years I haven’t said his name, but in writing I immediately slip into the present tense, as if he’s here, he’s back. Writing can bring him to life.One summer day in 1978, 11 years old, toward the end of a bright seaside afternoon, I left the broad stretch of beach with my brother Nicholas, aged 9. I don’t remember why. Facing the sea, we ran to the right, away from the family camp, and clambered round or over some rocks. On the other side we found a fresh patch of unmarked sand. I see this place as a cove, with dark rocks close in on both sides, rising steeply to cliffs. The new sandy beach doesn’t reach back very far.

The two of us are in the sea, jumping as the waves roll in. Until now I have tried not to know this and many times I’ve stopped, squeezed shut my eyes and closed the memory down. I can do that, crush it out of existence. All it costs me is the effort.

We were having fun, buffeted and breathless. I can believe I know this, even though the effort to forget has been immense. The memory is in ruins, but the foundations are traceable.

He was out of his depth. He wasn’t and then he was. I can’t remember everything, not each separate moment.

I don’t know how, but suddenly he was out of his depth. I think I tried to push him back toward the shore, but the logistics are confused and I, too, am up to my neck. With my feet touching the sand my mouth is barely above the water. The instinct, because I’m not a good swimmer, is to walk back in but when I feel with my toes the sand sucks out from beneath me. The next time I try, only the tips of my toes touch solid ground. The ocean floor sweeps from beneath me. Nicky is farther out into the sea than I am, and I don’t know how that happened either. Is he?

His head is to my left as I look toward the horizon. I’m looking to him, away from land and safety, so I must be worried. He’s farther out than me and too far to reach by walking, and anyway I’m in too deep to walk. I don’t understand how he got there. I search with my foot for solid ground and my head is under and I just about touch and the sand rushes out. I push back up. His neck is stretched taut to keep his nose and mouth in the air, and he is panicked into a desperate doggy-paddle, getting nowhere. He whines, his head back, ligaments straining in his neck, his mouth in a tight line to keep out the seawater.

I couldn’t reach him and I didn’t want to go in deeper. I shouted at him not to stand. He had to swim. I shouted he shouldn’t try to stand. He tried to put his foot down and his head went under.

Out of my depth, I was about to die. Nicky was trying to stand in water that was too deep, and in any case the undertow would drag him out. I decided to leave him. A conscious decision. I kicked my legs up and launched into a desperate crawl, face submerged, no breathing, a last resort to create forward momentum toward the shore. Front crawl was the fastest stroke over the shortest distance, though I didn’t really know how to do it, and if I stopped to breathe I would die. I smashed my arms and hands into the water, head down, feet thrashing, because I understood that for me it was now or never.

Faster! Harder!

I understood with absolute clarity that I had one go at this. Run out of breath too soon and I would drown, exhausted and unable to find my footing. Keep going and I might get close enough in to stand, to live.

The memory is unsatisfactory. I experience the pain of remembering though I can’t clearly remember. I was going to die so I decided to save myself, and staying alive took total concentration. I swam my frenzied approximate crawl until finally I had to breathe, and when my legs dropped down, my feet touched sand. The sand dragged me out, but I was far enough in to fight the undertow. I swam again, until I needed to breathe again. Chest-high in the water, waist-high, the sea was around my thighs and I could almost run, heaving my hips one way then the other, driving hard toward land, knees raised, escaping the water.

The two of us are in the sea, jumping as the waves roll in. Until now I have tried not to know this and many times I’ve stopped, squeezed shut my eyes and closed the memory down.I don’t remember looking back, or arriving at the camp on the main stretch of beach. I’m out of the water and running. I see a man. He is higher up, on rocks (or on a path above the rocks?). I tell him. . . I don’t know what; whatever I said isn’t part of what I know. I communicate the situation and the man stands up, gazes out to sea as if primed to make a decisive intervention. He takes off his sunglasses, and in a purposeful gesture hands them to the distressed and dripping boy.

I’m running again, to the right, over patches of hard sand between flat rocks, from one terrain to another. I remember looking down on myself, as if from above, running with the stranger’s metal-framed sunglasses and finding them an absurd responsibility to have accepted. I throw his stupid sunglasses to the ground and they smash on hard rock and I don’t care. I’ve broken an adult stranger’s sunglasses, intentionally, and I don’t care. I’m crying, I’m running. My face is out of control.

And that’s about it. Of the incident itself, that’s close to all I know.

My younger brother’s name is Nicholas Beard. He was nine years old, and I was with him in the water when he drowned. Events that happened before and after are a blank to me. I don’t know the name of the beach in Cornwall where he died or the date when the drowning took place. I’m not even certain of the month.

The general area is July or August 1978, the season of summer holidays, and 1978 because I was 11. I can’t remember everything and I can’t erase everything, however fiercely I’ve tried. The scar left by that summer disfigures the age of 11, and plenty more besides, but the month is obscured, the date lost to me. In nearly 40 years, either alone or with my family, the anniversary of my younger brother’s death has never been acknowledged or commemorated.

Which is an epic level of denial, because it can’t be that difficult to pin down a date. The headstone at his grave will have it, but until now I haven’t chosen to look. As it is, the older I get the harder it is to pretend that denial works as a strategy for sustaining inner peace. The memories I’ve wanted to suppress refuse to stay down, especially in stories I think I’ve invented.

Write what you know, they say. In my novel Damascus the main character Spencer Kelly is about 12 or 13 when his sister Rachel, two years younger, dies in a car crash. More recently I’ve been closing in. Lazarus Is Dead, also a novel, provides the biblical character Lazarus with a younger brother called Amos. As teenage boys, the brothers go swimming in Lake Galilee. Amos drowns.

He didn’t need to die, not in a fiction, but as early as primary school I learned in English Composition that the narrator can never die. If the narrator dies at the end of the story, how can he possibly tell it? I am alive and I get to tell the story. Only I haven’t told it, not really. In the novel, Lazarus comes back to life and doesn’t know what he owes, or what he should do with himself. Like him, I had a second chance. I write books. That’s what I do, as if proving I’m the one who survived.

*

From my experience of teaching creative writing I’m wary of shortcuts to Characterization. In particular, I distrust classroom exercises that involve a questionnaire:

· What does your character have in his pockets?

· What are your character’s favorite clothes?

· How does your character feel about what he has in his pockets?

· How does your character feel about the way he looks?

This is how a fiction writer is taught to fully realize a nonexistent character, as part of the creative process. This step is essential, because if a character fails to come alive, no one will care when he dies.

*

I concentrate on what I have, the boy in pieces.

Three baby shoes, a pair in white and one solitary blue shoe.

A blue tracksuit top (with a J.I. BEARD name tape, but I’m sure I remember this as the top Nicky wore in Cornwall)—it has a distinctive hexagonal patch saying GO, in green, sewn onto the left breast.

An invitation card with Nicholas written in italic red to my great-grandfather’s 100th birthday celebration. The date of my great-grandfather’s birth is misprinted and overwritten in blue biro (presumably on every invitation): 18 April 1878. As a family, it looks like we’re weak on dates.

A framed certificate from Devizes Junior Eisteddfod 1976, Piano Solo, Under 9, 80—Merit.

School bills.

A small transparent plastic bag: Cash’s 72 Name Tapes. By Appointment to her Majesty the Queen Manufacturers of Woven Name Tapes. In blue—N.P. BEARD. Unopened.

The Empire “Cumulative” Cricket Scoring Book, for invented cricket matches. Nicky has filled in dates for the new season—1978-79—but of the book’s possible 100 innings, only two games have started.

A selection of letters to and from.

Photographs, many single photographs, mostly dog-eared or creased. Others in a cardboard scrapbook, the prints glued or Sellotaped at the corners, the Sellotape as brown as the glue.

A pocket-sized Letts Schoolboys’ Diary 1978, bound in red plastic.

The blue floppy sunhat Mum called his cricket hat, but I’m not sure it is. It fits on my head. The label inside says Harrods, so the hat was school uniform, bought on our yearly trip to London. We didn’t go to London, as such. We drove up the M4 and parked at the Knightsbridge NCP, walk round to Harrods, bought school uniform and ate a roast-beef lunch in the Georgian carvery. Harrods was London, just as Cornwall was holiday England.

Two newspaper cuttings: Surf Boy is Fourth Victim is one headline. The other is Holiday Boy, 9, swept to death.

A blue-peaked gray school cap, name-taped, from Gorringes of Victoria, School and College Outfitters, Phone Vic. 6666, London, SWI, which looks antique even to me, and I’d have worn something similar. Size 6 ¾, with oil from Nicky’s hair shiny in the rust-back lining.

A folder marked Nicholas Beard, Termly Reports. Another reason not to die young: what will survive of us is our school reports.

*

In the attic I keep finding pieces of him. His birth certificate, and six Premium Bonds in his name, dated 3 June 1969. I’m amazed that before now no one has gone through these remnants looking for what’s left of him, but no one ever has. The family has shared a desire to postpone, and possibly delay forever, the acknowledgment of Nicky’s existence. And therefore also his nonexistence.

I’m old enough (at last) to appreciate more positive ways to cope with sudden death. Fear, I imagine, is one of the reasons we have distanced Nicky, but I did not shatter at the churchyard when I read the words on his gravestone, or when Mum revealed the date. We didn’t need to be so frightened—the finds from the attic haven’t overwhelmed me.

In fact, I feel rewarded by every object that connects to Nicky: he was real, he occupied a particular space of his own in the material world. Up in the attic I feel energized and useful. I pick out anything that might be relevant, and whenever I’m convinced I’ve salvaged all there is, I find something more.

__________________________________

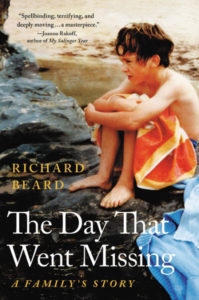

From The Day That Went Missing. Courtesy of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2018 by Richard Beard.