It's Not Coming, It's Here: Bill McKibben on Our New Climate Reality

“We are now truly in uncharted territory.”

To walk the roads through even a corner of Alberta’s vast tar sands complex is to visit a kind of hell. This may be the largest industrial complex on our planet—the largest dam on Earth holds back one of the many vast settling “ponds,” where sludge from the mines combines with water and toxic chemicals in a black soup. Because any bird that landed on the filthy water would die, cannons fire day and night to scare them away. If you listen to the crack of the guns, and to the stories of the area’s original inhabitants, whose forest was ripped up for the mines, you understand that you are in a war zone. The army is mustered by the Kochs (the biggest leaseholders in the tar sands) and ConocoPhillips and PetroChina and the rest, and their enemy is all that is wild and holy. And they are winning.

It is hideous, a vandalism of the natural and human world that can scarcely be imagined. I’ve spent years working to end it, and my efforts have been small compared to the unending fight of the people who live there. And yet, giant as this scar is, in itself it represents no real threat to the human game. The Earth is not infinite, but it is very large, and if you retreat far enough, even this scab (the single ugliest sight I’ve witnessed in a lifetime of traveling the planet) gets swallowed up in the vastness that is Canada’s boreal forest, and that in the vastness of North America, and that in the vastness of the hemisphere.

Likewise, to wake up in Delhi at the moment is to wake up in a gray, grim purgatory. The clatter and smell of one of the planet’s most crowded cities assail you as always, but some days the smog grows so thick you can’t see the end of the block. Walking down the pavement, you seem almost alone, and the city noise seems as if it must be made by ghosts. When the air is at its worst, when the smoke from the region’s farms burning off stubble combines with the exhaust of cars and buses and the cooking fires of the slums, it’s almost unbearable: in one recent outbreak, the international airlines scrubbed their flights into Delhi because the runway was invisible, and then cars began crashing on the highways, and then the city’s trains were cancelled due to poor visibility. Imagine how bad the air must be to cancel a train, which runs on a track. At a big international cricket match the next month, with pollution levels 15 times the global standard for safety, players began “continuously vomiting.” After halting play for 20 minutes, the umpire said, “There aren’t too many rules regarding pollution.”

Delhi’s air pollution may currently be the worst in the world, besting even the smoke-racked Chinese cities where the authorities installed giant LED screens to show video of the sun rising. Or maybe Lahore, in Pakistan, deserves the crown: particulate levels there have reached 30 times the safe level, producing a soupy brown haze likened by one journalist to a “giant airport smokers’ lounge.” Asian authorities routinely close schools because of the bad air, but because most homes lack filters, that doesn’t help much. A large-scale study found that, of the 4.4 million children in Delhi, fully half had irreversible lung damage from breathing the air. Around the world, pollution kills 9 million people a year, far more than AIDS, malaria, TB, and warfare combined. In the worst years, a third of the deaths in China can be blamed on smog, and by 2030, it may claim 100 million victims worldwide.

It is sick, sad, unnecessary—the biggest public health crisis on the planet. And yet, even it represents no existential threat to the human game. If the devastation of the tar sands is limited in space, this assault is limited in time. It can and will be solved, too slowly, with far too much human anguish, but that is the lesson from London, from Los Angeles, even from Beijing, which has begun, haltingly, to clear its air.

The list of such severe environmental problems grows ever longer: dead zones in the oceans where fertilizer pours off farms along with irreplaceable topsoil; great gyres of plastic waste spinning in the seas; suburbs spilling across agricultural land, and agricultural land overrunning tropical forest; water tables quickly sinking as aquifers drain. These issues rightly demand, and even rightly monopolize, our attention because the threats they represent are so stark and so immediate. And yet, one imagines that we will survive them as a species, impoverished in many ways, but not threatened in our basic existence. People, and other creatures, will be robbed of dignity—they’re all signs of a game badly played—but the game goes on.

The sea surface temperature has gone up by seven degrees Fahrenheit in recent years in parts of the Arctic.

But not every threat is like that. There’s a small category (a list with three items) of physical threats so different in quantity that they become different in quality, their effects so far-reaching that we can’t be confident of surviving them with our civilizations more or less intact. One is large-scale nuclear war; it’s always worth recalling J. Robert Oppenheimer’s words as he watched the first bomb test, quoting from Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” So far, the cobbled-together and jury-rigged international efforts to forestall an atomic war have worked, and indeed, for much of the last 50 years those safeguards, formal and informal, have seemed to be strengthening. That we have nuclear nightmares again is mostly testimony to the childishness of President Trump and his pal in North Korea—they seem nearly alone in not understanding “why we can’t use them.”

Second on that list of threats is the small group of chemicals that, just in time, scientists discovered were eroding the ozone layer, a protective shield that 99 percent of us didn’t even know existed. Had those scientists not sounded the alarm, we would have walked blindly off a cliff—literally, in many cases, as cataracts are one of the most common symptoms of being bathed in the ultraviolet radiation that the ozone layer blocks. Within a decade, the chemical companies had ceased their obstruction and the Montreal Protocol began removing chlorofluorocarbons from the atmosphere. The ozone hole over the Antarctic now grows smaller with each decade, and now scientists expect it will be wholly healed by 2060.

And the third, of course, is climate change, perhaps the greatest of all these challenges, and certainly the one about which we’ve done the least. It may not be quite game-ending, but it seems set, at the very least, to utterly change the board on which the game is played, and in more profound ways than almost anyone now imagines. The habitable planet has literally begun to shrink, a novel development that will be the great story of our century.

![]()

Climate change has become such a familiar term that we tend to read past it—it’s part of our mental furniture, like urban sprawl or gun violence. So, let’s remember exactly what we’ve been up to, because it should fill us with awe; it’s by far the biggest thing humans have ever done. Those of us in the fossil fuel-consuming classes have, over the last 200 years, dug up immense quantities of coal and gas and oil, and burned them: in car motors, basement furnaces, power plants, steel mills. When we burn them, the carbon atoms combine with oxygen atoms in the air to produce carbon dioxide. The molecular structure of carbon dioxide traps heat that would otherwise have radiated back out to space. We have, in other words, changed the energy balance of our planet, the amount of the sun’s heat that is returned to space.

Those of us who burn lots of fossil fuel have changed the way the world operates, fundamentally.

The scale of this change is the problem. If we just burned a little bit of fossil fuel, it wouldn’t matter. But we’ve burned enough to raise the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from 275 parts per million to 400 parts per million in the course of 200 years. We’re on our way, on the present trajectory, to 700 parts per million or more. Because none of us knows what a “part per million” feels like, let me put it in other terms. The extra heat that we trap near the planet because of the carbon dioxide we’ve spewed is equivalent to the heat from 400,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs every day, or four each second. As we will see, this extraordinary amount of heat is wreaking enormous changes, but for now, don’t worry about the effects; just marvel at the magnitude: the extra carbon released to date, if it could be amassed in one place, would form a solid graphite column 25 meters in diameter that would stretch from here to the moon.

There are perhaps four other episodes in Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history where carbon dioxide has poured into the atmosphere in greater volumes, but never at greater speeds—right now we push about 40 billion tons into the atmosphere annually. Even during the dramatic moments at the end of the Permian Age, when most life went extinct, the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere grew at perhaps one-tenth the current pace. The results, already, have been extraordinary.

By now, it’s a commonplace that record drought helped destabilize Syria, sparking the conflict that sent a million refugees sprawling across Europe.

In the 30 years I’ve been working on this crisis, we’ve seen all 20 of the hottest years ever recorded. So far, we have warmed the earth by roughly two degrees Fahrenheit, which in a masterpiece of understatement the New York Times once described as “a large number for the surface of an entire planet.” This is humanity’s largest accomplishment, and indeed the largest thing any one species has ever done on our planet, at least since the days two billion years ago when cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) flooded the atmosphere with oxygen, killing off much of the rest of the archaic life on the planet. “Faster than expected” is the watchword of climate scientists—the damage to ice caps and oceans that scientists (conservative by nature) predicted for the end of the century showed up decades early. “I’ve never been at a climate conference where people say ‘that happened slower than I thought it would,’” one polar expert observed in the spring of 2018. At about the same time, a team of economists reported that there was a 35 percent chance that the United Nations’ previous “worst-case scenario” for global warming was in fact too optimistic. In January 2019 scientists concluded the Earth’s oceans were warming 40 percent faster than previously believed.

“We are now truly in uncharted territory,” said the director of the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2017, after final data showed that the previous year had broken every heat record. He was speaking literally, not metaphorically—we were off the actual charts. That summer, an Atlantic hurricane developed well to the east of where any such storm had ever been seen before. Instead of crashing into Mexico and Louisiana and Florida, it spent its fury on Ireland and Scotland. When the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed the storm forecast on its computerized maps, the image looked odd: the cone of winds stopped abruptly in a straight line at latitude 60 degrees north—because, it turns out, it had never occurred to the people programming the forecasting models that a hurricane would reach that line. “That’s a pretty unusual place to have a tropical cyclone,” the programmer said. “Maybe that’s something we’ll have to go back and revisit what the boundary is.” Maybe so.

![]()

If you find a stout enough man, you can give him a pretty hefty shove and not much happens (unless, with some justification, he gets mad). When the global warming era began, we did not know how stout the planet was—it was possible that its systems would tolerate a lot of pushing without much change. The earth seems, after all, like a robust place: its ice sheets are miles thick, its oceans miles deep. But the lesson of the last 30 years is unequivocal: the planet was actually finely balanced, and the shove we’ve given it has knocked it very much askew. Let’s look for a long minute at what has happened so far, remembering always that we’re still in the early stages of global warming and that things will proceed inevitably from worse to worse yet and then keep on going.

Consider something fairly simple: the planet’s hydrology, the way water moves around the earth. Water evaporates off the surface of the earth and the ocean, and then falls as rain and snow, an endless pump for keeping the earth’s essential fluid in constant motion. But if you increase the amount of heat (of energy) in the system, it’s like turning the dial on that machine to the right: it does more work. Evaporation increases when the temperature rises, and hence arid places grow drier. We call this phenomenon drought, and now we see it everywhere.

Cape Town, among the most beautiful cities on earth, spent 2018 flirting with going completely dry. Its four million residents were rationed 23 gallons per person per day, enough for a shower, as long as you didn’t want to take a drink or flush the toilet. Why? Because of a three-year drought that scientists said, based on past history, should be expected about once a millennium. But of course the phrase “based on past history” no longer makes sense, because that history took place on what was essentially a different planet with a different atmospheric chemistry.

That’s why there are versions of the Cape Town story on every continent. A couple of years earlier it was São Paulo, home to 20 million Brazilians, that was turning off the taps. Bangalore may be the highest-tech city in the developing world, with nearly two million IT professionals, but it’s also faced drought every year since 2012. The Po River Valley is Italy’s agricultural heartland, supplying 35 percent of its crops, but its average temperature is almost four degrees Fahrenheit higher than it was in 1960, and its rainfall has fallen by a fifth. So, by the summer of 2017, an enormous drought forced mayors and governors there to start rationing water. “The Po Plain used to be extraordinarily water-rich, and hence we got used to a situation where water has always been available,” said one local official. Most of Italy was affected—Rome shut off its network of public drinking fountains, the largest in the world, and the Vatican turned off the water in the Baroque fountains of St. Peter’s Square. But none of it was enough—by September, the source of the Po, on Monviso, in the Cottian Alps, was dry. Petrarch talked about the source of the Po, and so did Chaucer and Dante. But they lived on a planet with 40 percent less carbon dioxide.

There was hope, 30 years ago, that global warming might somehow limit itself, that raising the temperature might trigger some other change that would cool the planet.

As land dries out, it often burns. Humans have converted more and more forest into farmland, which reduces the number of fires overall, but where there’s something to combust, fire has become a menace of a different kind. Jerry Williams, the former head firefighter for the US Forest Service, told a conference not long ago that “my first experience with a really unimaginable fire was in Northern California late in August in 1987,” when a thousand blazes broke out simultaneously. “I remember saying, ‘Jesus, we will never see anything like that again.’ And the next year we saw Yellowstone.” Now, he said, “it seems like every year we see a ‘worst’ one. And the next year we see a worse one yet. They’re unbounded.”

As Michael Kodas reports in his recent book, Megafire, fire season is on average 78 days longer across the American West than it was in 1970, and in some parts, it essentially never ends; since 2000, more than a dozen US states have reported the largest wildfires in their recorded histories. We know about those fires because there are reporters nearby, and urban populations to smell the smoke, but there are also now much vaster blazes virtually every spring and summer across Siberia, which we can track only with satellite photos. In fact, by this point there’s an obvious rhythm to the global danger: prolonged drought, then a record heat wave, then a spark.

Australia’s McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index used to top out at 100, but in 2009, after a month of record heat and the lowest rainfalls ever measured, the index reached 165, and 173 people died in a blaze that raced through the suburbs. In 2016, the city at the heart of Alberta’s tar sands complex, Fort McMurray, had to be entirely evacuated after a low snow-pack gave way to a record spring heat wave and, soon, a May blaze that spread to a million and a half acres, chasing 88,000 people from their homes. In 2018, 80 people died in Attica, in the heart of classical Greece, when a firestorm took off amid record heat; those who survived did so only by diving into the Aegean Sea, even as “flames burned their backs.” Two dozen people who couldn’t make it to the beach just formed a circle and embraced one another as they died.

Sometimes humans start the fires—sparks from golf clubs hitting rocks have set off several Southern California blazes, and in Utah, target shooters managed to ignite twenty blazes during the drought of 2012. But in a deeper sense, humans help start all of them: each degree Fahrenheit we warm the planet increases the number of lightning strikes by 7 percent, and once fires get going in our hot, dry new world, they are all but impossible to fight. These blazes “make up a new category of fire,” Kodas writes, “exhibiting behaviors rarely seen by foresters or firefighters. The infernos can launch fusillades of firebrands miles ahead of the conflagration to ignite new blazes in unburnt forests and communities. The flames create their own weather systems, spinning tornadoes of fire into the air, filling the sky with pyrocumulus clouds that blast the ground with lightning to start new fires, and driving back firefighting aircraft with their winds.” They “cannot be controlled by any suppression resources that we have available anywhere in the world,” said one Australian researcher.

And the devastation they leave behind—well, you’ve seen the rows of burned-out houses on your Facebook feed. But imagine all the other effects. In the spring of 2017, after the obligatory deep drought and record heat, Kansas saw the largest wildfire in its history. There weren’t many houses in the way, but there was lots and lots of barbed-wire fencing, and all those wooden posts burned to stumps. New fence costs ten thousand dollars a mile, and at many ranches, that alone meant two million dollars or more in uninsured losses. Far worse were the cattle: At a ranch outside Ashland, “dozens of Angus cows lay dead on the blackened ground, hooves jutting in the air. Others staggered around like broken toys, unable to see or breathe, their black fur and dark eyes burned, plastic identification tags melted to their ears,” the New York Times reported. A 69-year-old rancher walked among them with a rifle. “They’re gentle,” he said. “They know us. We know them. You just thought, ‘Wow, I am sorry.’ You think you’re done and the next day you got to go shoot more.”

![]()

That global pump I’ve described doesn’t just suck water up; it also spews it back out. An easy rule of thumb is that for every drought, a flood. Occasionally they’re in the same places a few months apart, but another rule of thumb: dry places get dryer, and wet places wetter.

So: ocean temperatures had risen about a degree Fahrenheit off the Texas coast in recent years, which means, on average, about 3 to 5 percent more water in the atmosphere. And when Hurricane Harvey wandered across the Gulf in August 2017, it crossed a particularly warm and deep eddy, intensifying “at near record pace” into a Category 4 storm. But it wasn’t its winds that tied it with Katrina as the most economically damaging storm in American history; it was the rain, which came down in buckets. Not in buckets—in football stadiums. Thirty-four trillion gallons, enough to fill 26,000 New Orleans Superdomes. That’s 127 billion tons, enough weight that Houston actually sank by a couple of centimeters. In places, the rainfall topped 54 inches, by far the largest rainstorm in American history. “Harvey’s rainfall in Houston was ‘biblical’ in the sense that it likely occurred around once since the Old Testament was written,” one study concluded.

Because we’ve warmed the atmosphere, the odds of a storm that could drop that much rain on Texas have gone up sixfold in the last 25 years. Three months after the storm, another study found that the rainfall was as much as 40 percent higher than it would have been from a similar storm before we’d spiked the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. When Hurricane Florence hit the Carolinas in September 2018, it set a new record for East Coast rainfall—the storm dumped the equivalent of all the water in Chesapeake Bay.

This isn’t something that happens just in Houston. In Calcutta, home to 14 million people, none of whom is an oil baron and a third of whom reside in flood-prone slums, the number of “cloudburst days” has tripled in the last five decades. “This is what we say to God,” one pavement-dwelling mother of four explained. “If a storm comes, kill us and our children at once so no one will be left to suffer.” In the Northeast United States, where I live in landlocked Vermont, we’ve watched extreme precipitation (two inches or more of rain in twenty-four hours) grow 53 percent more common since 1996. (Since 1996, when the first flip phone was sold.) All that water cascades over all that we’ve built these last few centuries—a 2018 New York Times survey showed that 2,500 of America’s toxic chemical sites lie in flood-prone areas. Harvey, for instance, swamped a factory that spilled huge quantities of lye. In effect, we’ve put the planet on a treadmill, and we keep pushing up the speed. We’re used to the idea that geologic history unfolds over boundless eons at a glacial pace, but not when you’re changing the rules.

In the spring of 2017, after the obligatory deep drought and record heat, Kansas saw the largest wildfire in its history.

Actually, perhaps it is proceeding at a glacial pace; it’s just that “glacial” means something different now. All those Hiroshimas’ worth of heat are thawing ice at astonishing speed. Much of the sea ice that filled the Arctic in the early pictures from space is gone now—viewed from a distance, Earth looks strikingly different. Everything frozen is melting. A few years ago, the mountaineer and filmmaker David Breashears took his camera into the Himalayas to retake the first images sent home from the roof of the world, during the Mallory expedition of 1924. He spent days climbing to the same crags, and catching the same glaciers from the same angles. Only, now they were hundreds of vertical feet smaller—a Statue of Liberty shorter. And once ice starts to thaw, it’s hard to slow down the process. A 2018 study concluded that even if we stopped emitting all greenhouse gases today, more than a third of the planet’s glacial ice would melt anyway in the coming decades.

![]()

For the moment, though, don’t think about the future. Just think about what we’ve done so far, in the early stages of this massive transformation. Climate change is currently costing the US economy about $240 billion a year, and the world, $1.2 trillion annually, wiping 1.6 percent each year from the planet’s GDP. That’s not much yet—we’re rich enough as a planet that it doesn’t profoundly change the overall game—but look at particular places: Puerto Rico, say, after Hurricane Maria ripped it from stem to stern with Category 5 winds. It was the worst natural disaster in a century in America—in the spring of 2018, a Harvard study estimated it had killed nearly 5,000 people, twice the number who died in Katrina—and the economic toll guaranteed it would go on stunting lives for years: the total cost was north of $90 billion, for an island whose pre-storm GDP was $100 billion a year. Economists calculated that it would take 26 years for the island’s economy to get back to where it had been the day before the storm hit—if, of course, another hurricane didn’t strike in the meantime.

Or look at people living so close to the margin that small changes make a huge difference. I noted earlier that we’ve seen a steady decline in extreme poverty and hunger. “Our problem is not too few calories but too many,” Steven Pinker wrote smugly. But late in 2017, a UN agency announced that after a decade of decline, the number of chronically malnourished human beings had started growing again, by 38 million, to a total of 815 million, “largely due to the proliferation of violent conflicts and climate-related shocks.” In June 2018, researchers said the same sad thing about child labor: after years of decrease, it, too, was on the rise, with 152 million kids at work, “driven by an increase in conflicts and climate induced disasters.”

Those “conflicts,” too, are ever more closely linked to the damage we’ve done to the climate. By now, it’s a commonplace that record drought helped destabilize Syria, sparking the conflict that sent a million refugees sprawling across Europe and helped poison the politics of the West. (And a 2018 World Bank study predicted that further climate change would displace as many as 143 million people from Africa, South Asia, and Latin America by 2050. The authors whimsically urged cities to “prepare infrastructure, social services, and employment opportunities ahead of the influx.”) But there are a hundred smaller examples.

On top of Mount Kenya, two-thirds of the ice cover has disappeared; ten of the eighteen glaciers that once watered the surrounding region are gone altogether. Herders, whose pastures are turning to dust, have started driving their cattle into the farmland nearer the mountain. “Our cows had nothing to eat,” explained one man. “Would you let your cow die if there is grass somewhere near?” The farmers who till that land (traditionally from different ethnic groups) have fought back hard, and people have died. “I have not slept for two days,” one farmer said. “If I do, they will bring their cows and let them loose in our farms. They are lurking, waiting for us to sleep, then bring their cows and goats to eat our cabbages and maize.” There are studies that try to quantify these changes—one standard deviation increase in temperature supposedly increases conflicts between groups by 14 percent—but you hardly need them. Common sense will do. The planet is crowded. As we begin to change it, people are pushed closer together. We know what happens next.

![]()

There was hope, 30 years ago, that global warming might somehow limit itself, that raising the temperature might trigger some other change that would cool the planet. Clouds, perhaps: as the atmosphere grew moister with increased evaporation, more clouds might form, blocking some of the incoming sunlight. No such luck; if anything, the kinds of clouds we’re producing on a hotter planet seem to be trapping more heat and making it hotter still.

Such feedback loops, it turns out, lie buried in all kinds of earth systems, and so far, they’re all making the problem worse, not better. When the white ice melts in the Arctic, it stops reflecting the sun’s rays back out to space: a shiny mirror is replaced with dull blue seawater, which absorbs the sun’s heat. The sea surface temperature has gone up by seven degrees Fahrenheit in recent years in parts of the Arctic. Hidden ice, locked beneath the soils of the Arctic, is now starting to melt fast, too, and as that permafrost thaws, microbes convert some of the frozen organic material into methane and carbon dioxide, which cause yet more warming—perhaps, say scientists, enough to add a degree and a half Fahrenheit or more to the eventual warming.

New studies also show that degradation of tropical woodlands, from wildfire, drought, and selective logging, has turned them from sinks for carbon into sources of more carbon dioxide. This transition is important. When economists scoffed at books such as Limits to Growth, insisting that scarcity, and the resulting higher prices, would spur the search for new sources, they had a point: we haven’t run out of copper; and oil obviously keeps flowing. But places to put our waste? Those are ever harder to come by, as the increasing temperature weakens the ability of forests and oceans to soak up carbon. Should this weakening continue, the New York Times noted, “the result would be something akin to garbage workers going on strike, but on a grand scale: The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would rise faster, speeding global warming even beyond its present rate.” And that’s what seems to be happening. Even as our emissions rise more slowly, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere keeps spiking faster.

But, again, we’re getting ahead of the story. Right now, just focus on what we’ve already done, how much we’ve already changed our world. Consider California, the Golden State, long the idyllic picture of the human future. It endured a horrific five-year drought at the start of this decade, the deepest in thousands of years—so deep that the state was tapping into groundwater that was 20 thousand years old, rain that fell during the last Ice Age; so deep that the state’s Sierra Nevada range rose an inch just because 63 trillion gallons of water had evaporated; so deep that it killed 102 million trees, a blight “unprecedented in our modern history,” in the words of the Los Angeles Times. (Sugar pines should live 500 years, but “everywhere you walk, through certain parts of the forest, half these big guys are dead,” said one forester.) The drought ended in the winter of 2017, when the rains finally came, an endless atmospheric river that poured off the hot Pacific into the high mountains. Everyone breathed a sigh. California’s authorities said, of course, that they understood the reprieve was only temporary, but they could be forgiven for relaxing a little as the hills turned lush and green. (Anyway, they were having enough trouble with the floods that the record rainfall produced: the deluge caused almost a billion dollars in damage, for instance, to the nation’s highest dam.)

The summer of 2017, though, proved hotter and drier than even in the worst years of the drought, and all that green grass soon browned up, and in October, a firestorm swept through Napa and Sonoma. Despite all the TV alerts and text warnings, it killed more people in a shorter time than any American fire in a century—old people, especially, who simply couldn’t outrun the flames. Reporters described the “apocalyptic scene” in neighborhoods that, 24 hours earlier, came as close to representing the good life as any place on earth. People died in swimming pools where they’d taken shelter, the tiled sides as “hot as oven racks.” In Santa Rosa, “the aluminum wheels on cars melted and dripped down driveways like tiny rivers of mercury before hardening. A pile of bottles melded together into a tangle so contorted it looked like a Picasso sculpture. Plastic garbage bins were reduced to mere stains on the pavement.”

But that was October, right at the end of the state’s traditional fire season. So, people breathed a sigh again, and began the work of cleaning up, knowing they had a little time—until, in December, record heat and dryness in Southern California touched off what became the largest blaze in California history, a blaze that “jumped ten-lane highways with unsettling ease” and threatened the homes of Rupert Murdoch, Elon Musk, and Beyoncé.

It burned till the New Year, and then, as 2018 began, people breathed a sigh again, and welcomed the prospect of a little winter rain. The first storm hit, and it brought prodigious amounts of water, half an inch inside of five minutes in some places. That water fell on the burned-over hills, where there were no plants left to hold the flood, and so it turned into a mudslide. Twenty-one people died. Those who survived remembered the sound, a rumbling like a freight train. “It buried houses and cars and people,” said the writer Nora Gallagher, who lived nearby. “It buried the freeway and the train tracks. The creeks ran black with ash. It went all the way to the ocean. A body of a man was found there on the beach. Not far away from him was the body of a bear.”

The rest of 2018 was no better. By early August, the record for the largest fire in state history had fallen again, to a massive blaze in the Mendocino area; Yosemite Valley was closed “indefinitely” as flames licked at its access roads; and meteorologists were trying to make sense of a vast “fire tornado” that rose 39,000 feet above the city of Redding and twisted so violently it stripped the bark from trees. And then, in autumn, came the most gruesome fire of all, in the Sierra foothills above Chico. After the fall “rainy season” delivered a seventh of an inch of precipitation, the town of Paradise exploded in flames; people died by the score in their cars as they tried to flee down narrow, burning roads. The president blamed the conflagration on “forest mismanagement” and recommended “raking”; meanwhile forensic teams tried to recover the victims’ DNA from the ashes of burned-out subdivisions.

This is our reality right now. It will get worse, but it’s already very, very bad. Nora Gallagher again:

Climate believers, climate deniers, deep in our hearts we think it will happen somewhere else. In some other place—we don’t actually say this but we may think it—in a poorer one, say, Puerto Rico or New Orleans or Cape Town or one of those islands where the sea level is rising. Or it will happen in some other time, in 2025 or 2040 or next year. But we are here to tell you, in this postcard from the former paradise, that it won’t happen next year, or somewhere else. It will happen right where you live and it could happen today. No one will be spared.

![]()

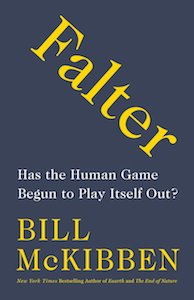

From Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? by Bill McKibben. Published by Henry Holt and Company April 16th 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Bill McKibben. All rights reserved.

Bill McKibben

Bill McKibben is a former New Yorker staff writer and the founder of the grassroots climate campaign 350.org. He is the Schumann Distinguished Scholar in environmental studies at Middlebury College.