It’s an Honor Just to Be Asian: Sandra Oh on Systemic Racism in Hollywood

“For the first time, I’m finally getting film roles where my character’s name is Korean.”

Hollywood has never truly known what it has in Sandra Oh, who has quietly built a career as one of the most talented, adaptable, and appealing actors in the business, without ever receiving the industry recognition she truly deserves; without ever being talked about as an “A-list” performer; without ever getting offers to play above-the-title roles.

That is, until 2018, when BBC America offered her the role of Eve Polastri in their adaptation of crime novelist Luke Jennings’s Villanelle novels—a white character in the original novels. Oh’s performance was universally acclaimed, garnering her a Lead Actress Emmy nomination. But for many of us, the line she uttered in the show’s opening musical number was the most memorable part of the night: when told by the hosts that it was the first nod in the category ever given to an Asian actress, she responded, “It’s an honor just to be Asian.” Oh shared with us the long road she walked to get to that point, and why the line sums up how she feels today, and how she hopes future generations will feel as well.

*

I grew up outside Ottawa, Canada. I began dancing when I was four. My parents made me do it because I was pigeon-toed and they heard it was a way to fix that, but I loved it—I loved the sensation of being onstage and moving my body and expressing myself, and just being as big and as truthful as possible. Then, at age 10, I did my first play in school, The Canada Goose, and that opened everything for me. There was nothing like the feeling of connecting with and reaching an audience for me. I was hooked. At age 15, I started working in front of the camera. At the time, I was in a student improv group called Skit Row High, like “Skid Row”; it was a bad pun but a very good improv troupe. Alanis Morissette, who’s from Ottawa, was a part of our troupe for a hot second—I actually sang backup for her in one sketch!

One of the girls in the troupe had an agent, and her agent asked if she knew any young Asian actresses. Well, she did—me—so I got signed, and I started doing things like PSAs and industrial videos. My first on-camera job was an anti-drinking-and-driving short film. I learned a lot from that, no kidding.

I always had a basic understanding that I was an Asian person in a white society. I grew up in Canada, with a lot of safety and privilege in a close-knit Korean Canadian community. But it was a small community and church, in a very white community. So yes, there was always the sting of knowing I couldn’t go out for the lead parts.

But I was extremely driven, and I wanted to do everything. I was in this high school show called Denim Blues, which was sort of inspired by Degrassi High. And then I was on another show where I was, like, the best friend of the best friend—basically two girls away from the blond girl. These were small roles, and I was clearly not a priority, the makeup artists never understood how to do my face, but I didn’t give a shit why I got a job or how small my role was. I just wanted to be in front of that camera, so I took it all.

I’d gone from a place of tremendous possibility and confidence when I was very young to not even being able to see myself on the page.

And then after I left school, I got the lead in a film called The Diary of Evelyn Lau for the Canadian Broadcasting Channel, based on Evelyn’s book about her life on the streets. And then I met Mina Shum and was able to star in her film Double Happiness. I was 21, and these experiences made me realize how much I had to give, and how eager I was to give the world all my work, all my soul, and all my talent. So I moved to Hollywood.

I think it’s good to land in Hollywood when you’re young and driven—you have a little bit more energy to push through things. But there was this very specific moment I experienced when the systemic racism that we experience as Asian artists just hit me. It was when I was first taking meetings with agents. And one in particular, she was a big agent, and very intimidating, and she made me wait a long time. When she finally saw me, she said: “Listen. I’m going to tell you the truth, because no one else will. Go home. Go back home and get famous. Because I can tell you, I have an Asian actress in my roster and she hasn’t gone out for anything in six months. There’s really no place for you here.”

And at this point, I’d starred in A-level theater. I’d been nominated for the equivalent of the Best Actress Emmy in Canada, the equivalent of Canada’s Best Actress Oscar—and I’d won.

So I thought to myself, where else could I go to get famous, if not here? I remember going back to the place where I was staying and calling my mentor and just shaking and crying. I could have quit then and gone home.

But I was extremely driven.

I stuck it out. I got some guest-starring roles and did short films. And then the following year, I landed a regular role in HBO’s Arli$$, and I did that for six years. And even then, after that show ended, it didn’t open any real doors for me. I did a couple of indie films, including Sideways, which got great reviews, but that didn’t open any doors either. I was still just getting offers for supporting parts. So I finally set myself a growth goal: I wanted to get to the point where I felt I had the ability to walk away.

Then I got a call for Grey’s Anatomy. They brought me in for the role Chandra Wilson eventually got: the hospital chief of staff, Dr. Bailey. But as I read the script, I realized that the show was really the interns. It was a show about students and teachers, and the students were the meat of it. So I asked my agent what other roles were open, and it turned out they hadn’t cast Cristina at that point. I looked at the part, and said to myself, “This is a better fucking role.” She’s the antagonist in the pilot. Cristina and Meredith Grey meet, and they’re instant rivals.

So they brought me in to test for Dr. Bailey, but I was adamant I wanted to get the shot to play Cristina instead. And because I’d gotten there early, I ran Cristina’s lines with them, just so Shonda Rhimes and the other executive producers could see what I could do as Cristina. After that, as I was waiting to do my test, my manager called and said, “Walk out.” You have to sign your contract before you test, and they weren’t willing to sign the deal my team thought I deserved. Well, that was my growth goal: to be able to say no. So I said, “I have to leave. Bye!” And I walked out of the audition. And they gave me the role! They cast me, and I never even tested.

A lot of it is timing: the timing of Killing Eve, the timing of Crazy Rich Asians, the timing of society, ultimately, being ready for me to be where I wanted to be.

I played Cristina—they gave her the last name “Yang” after they cast me—for 10 seasons. And I’m so thankful for the opportunity. But I got the role because I was willing to walk away, and I always said to myself that I would hold on to that willingness to say no, to leave a situation if it was no longer feeding me or challenging me. And after a decade doing a role, you get to that point. So I did let Cristina go, and it was a painful but necessary decision.

I was nominated for an Emmy every year for five years for playing Cristina Yang. I won a Golden Globe and a Screen Actors Guild award for Best Supporting Actress. Even then, when I left in 2014, no job offers. So I just did what I did early in my career: concentrated on growing as an actor. I did a lot of theater. I did another film with Mina Shum. I worked with John Ridley. And it dawned on me that for all of my success, I was just never going to have the same career trajectory as Charlize Theron or any of the Emmas or any of the Jennifers.

Here’s a sign of how beaten down I felt. When my agent called me to say they were offering me Killing Eve, I didn’t know what part I was being offered. I looked through the script and I couldn’t see myself in any of the characters. And that’s when my agent told me that they wanted me for the lead. For Eve. The character in the title.

And that’s the moment that I realized how deep the internalized racism had been for me by that point in my career. I couldn’t even see the part I was supposed to be playing. I’d gone from a place of tremendous possibility and confidence when I was very young to not even being able to see myself on the page.

So things have obviously been different in the past few years. But a lot of it is timing: the timing of Killing Eve, the timing of Crazy Rich Asians, the timing of society, ultimately, being ready for me to be where I wanted to be. To let me represent who I really am.

We have a little bit more freedom to write and talk about what we want to write and talk about.

That was summed up by the line they gave to me in the opener of the 2018 Emmys. I was up for a Lead Actress Emmy for Killing Eve, and I had tough competition, and they asked me to say this line about being nominated: “It’s an honor just to be Asian.” And I jumped on it. I knew I could do the line, make it funny and make it true, because it was true. I wasn’t worried that it would be taken the wrong way. But you just don’t know when something’s going to go viral. Everyone was talking about it the next day, and even then I thought it would bubble up and fade away. Until the shirt. Jeff Yang made the shirt, and the shirt became a thing. I wore it on Instagram with my family before the Golden Globes. I wore it when I hosted Saturday Night Live! I’m so glad it happened, because I see people wearing it all over as just a celebration of pride in being ourselves.

That’s something I’ve tried to bring to my choices as an actor. In the third season of Killing Eve, I got them to set it in New Malden, which is a Koreatown in the UK—and I could do that because I was also an executive producer. By that point in the story, Eve needs to retreat and to find a sense of home. Seeing her make mandu spiritually grounds the character. Hearing Korean spoken gives flavor to her background. And for the first time, I’m finally getting film roles where my character’s name is Korean.

That’s significant for me—people are calling me by a Korean name on-screen. I’m doing Umma, a psychological horror film written and directed by Iris Shim, and it’s very significant for me, in part because I do not speak Korean and I had to learn Korean for it. Just deeply confronting my ancestral language was very, very challenging. And then there’s Raya and the Last Dragon, which is so amazing, because Awkwafina is so fucking busy, and there are two kids in it who are going to be fucking busy, and Kelly Marie Tran’s dance card is full—that is what we need to see, our next generation out there working. If the industry is going to change, that’s how it’s going to change. We have a new generation of storytellers coming up. We have a little bit more freedom to write and talk about what we want to write and talk about. We aren’t as afraid it’s all going to go away if we wake up. It’s been thrilling for me just to have been able to be a part of that.

You could say, it’s an honor.

_____________________________

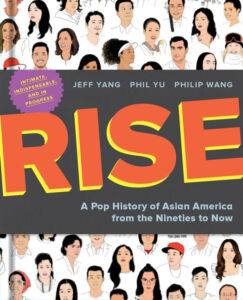

Excerpted from Rise: A Pop History of Asian America from the Nineties to Now by Jeff Yang, Phil Yu, and Philip Wang. Used with permission of the publisher. Copyright © 2022. Reprinted by permission of Harper.

Jeff Yang, Phil Yu, and Philip Wang

Jeff Yang has been observing, exploring, and writing about the Asian American community for over thirty years. He launched one of the first Asian American national magazines, A. Magazine, in the late '90s and early 2000s, and now writes frequently for CNN, Quartz, Slate and elsewhere. He has written/edited three books: Jackie Chan's New York Times best-selling memoir I Am Jackie Chan: My Life in Action; Once Upon a Time in China, a history of the cinemas of Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Mainland; and Eastern Standard Time: A Guide to Asian Influence on American Culture. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Phil Yu is the founder and editor of the popular Asian American news and culture blog, Angry Asian Man, which has had a devoted following since 2001. His commentary has been featured and quoted in Washington Post, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, NPR, and elsewhere. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Philip Wang is the co-founder of the hugely influential production company Wong Fu Productions. Since the mid 2000s, his creative work has garnered over 3 million subscribers and half a billion views online, as well as recognition from NPR and CNN for its impact on Asian American representation. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.