It Was All Greek to Her: With the Sappho-Obsessed in 1900s Paris

Eva Palmer Sikelianos, Pre-Modern Modernist

In the summer of 1900, Eva Palmer was reading the lines of Sappho in the company of her friends Renée Vivien and Natalie Clifford Barney, preparing for a series of Sapphic performances in Bar Harbor, a summer island resort on Mount Desert Island off the coast of Maine. Of the three women, Barney and Vivien (who was later christened, in a portrait, “Sapho 1900”) are well known as formative members of a Paris-based literary subculture of self-described women lovers, or “Sapphics.”

In a period that scholars have identified as “pivotal” in delineating modern lesbian identity, they interwove the fragmented texts of Sappho in their life and work, making the archaic Greek poet Sappho of Lesbos the quintessential figure of female same-sex desire and Sapphism, or lesbianism. They appear in the history of gay and lesbian sexuality as the women who contributed substantially to the turn-of-the-century decadent rewriting of Baudelaire’s lexicon of the sexualized woman.

Eva Palmer is largely absent from this history. She has made cameo appearances as the “pre-Raphaelite” beauty with “the most miraculous long red hair” who performed in two of Barney’s garden theatricals in Paris. Yet Eva’s correspondence, along with such sources as photographs and newspaper coverage, indicate that she participated in many more performances. From 1900 to the summer of 1907, the years when she moved with Barney between the United States and Paris, she developed a performance style that complemented the poetic language of Vivien and Barney by implicating Sappho in the practice of modern life. Eva’s acts helped transform the fragmented Sapphic poetic corpus into a new way of thinking and creating, before her differences with Barney propelled her to move to Greece to live a different version of the Sapphic life.

*

But what was Greece to Eva? By what journey of intellect and desire had she come to embrace this particular Greek prototype?

A notion that the new world found creative ground in old things was integral to Eva’s 19th-century upbringing. It aligned with the progressive ideas of her parents, both from prominent American families and advocates of well-reasoned social and political change to counter the effects of industrialization. Her mother, Catherine Amory Bennett, a member of the Amory family descended from Salem merchants and part of Boston’s traditional upper class, was a classically trained pianist who dedicated herself to the arts and progressive causes such as women’s suffrage. She gathered musicians in the family home to play in her small orchestra or to sing. Operatic divas Nellie Melba, Lillian Nordica, Emma Eames, Marcella Sembrich, and especially Emma Calvé were near the hearts of Eva and her siblings.

Eva’s father, Courtlandt, claimed he was descended from a knighted crusader and an ancestor who came over on the Mayflower. Trained as a lawyer at Columbia Law School, he spent his days “investigat[ing] for himself the questions, the problems, the mysteries of life. . . . No error could be old enough, popular, plausible, or profitable enough, to bribe his judgment or to keep his conscience still.” When he purchased a stake in Gramercy Park School and Tool-House (also known as the Von Taube School, after its originator and director, G. Von Taube), he supported its “new education” model of self-directed learning harmoniously combining theoretical and practical learning to prepare students for a business or scientific course. Yet he also directed pupils to study “Greek, French, German and English systems of philosophy, following his motto, “old things are passing away; behold, old things are becoming new.” This was his willful misreading of the passage in 2 Corinthians 5:17 that reads “all things are become new.”

Such enactments confirmed the sense that America was rooted in Greek culture.

Old Greek things were deeply ingrained in the look and feel of the world that these Mayflower descendants had inherited. Greece entered America (as it did Germany and Britain) as a country of the imagination, a special locus of aesthetic and intellectual origins, practically from the country’s founding moments. Initially the founders filtered Greece into American self-governance through the guise of Roman republicanism, considered a more congenial model than Athens’s direct democracy. Then, around the turn of the 19th century and coinciding with the receding of fears of the “perils of democracy,” American elites began drawing visible lines of affiliation that filled the gap between the new world and ancient Greece through a variety of Greek “revivals,” in architecture, education, and more.

*

Over time and coinciding with her coming of age in the late 1800s, changes in the value given to Greek learning broadened its social reach. Hellenism was proposed as an antidote to the crude anti-intellectualism of industrial society. It became a “platform for the perfection of the inner self.” Thus imitation of the Greeks moved from elite domains of scholarship and governance to popular spheres such as athletics—for example, when the American team competed successfully, dominating the gold medal tally in the first international revival of the Olympic Games, held in Athens in 1896. Imitation of Greek prototypes became a private occupation too when figures such as the tragic heroine Antigone were upheld as good models for women of the rising middle class.

During Eva’s adolescence, as women began gaining access to higher education, they also took on leading roles in reforming American culture. In the public sphere, they actively sought to translate classical models for new purposes, which were as pointedly sociopolitical as they were scholarly.

A case in point was the solidly humanities-based curriculum of Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, which Eva completed in 1891. As a day and boarding school, Miss Porter’s adopted a Yale preparatory curriculum for girls in grades nine to twelve. Even more revolutionary was the classically grounded humanistic curriculum that Eva followed at Bryn Mawr College, a school promising academic rigor equal to that of Harvard and Yale. After passing stiff entrance exams in Latin to gain entry as a twenty-two-year-old adult in 1896, she took advanced Latin and beginning and intermediate Greek classes there.

She was likely practicing some form of “inversion” in the sexual sense in her dormitory room in Radnor Hall in the spring of 1898.

At Bryn Mawr, Eva would have encountered Sappho on many fronts. From the mouth of the college’s president, M. Carey Thomas, who set the school’s high-minded direction, she would have heard Sappho named “the greatest lyric poet in the world,” an exception in history, a sign of women’s as yet untapped genius, and call for the necessity of their solidarity. Thomas was the same person who established the goal that work done in women’s colleges should be “the same in quality and quantity as the work done in colleges for men.”

Eva’s courses in Latin and Greek put that principle into effect by requiring that female students acquire skills in the original languages. They had to know the sources and stay informed about archaeological discoveries, such as the unearthing of new papyrus scraps of Sappho’s poetic fragments. Perhaps it was for them that “M. Maspero, the Director of Explorations in Egypt,” included the detail that “he detected the perfume of Sappho’s art” in those scraps in the sands of Oxyrhynchus. In her Latin studies Eva would have encountered stories of Sappho’s life in Ovid’s Heroides, or lingered on Catullus’s line about the young woman who made herself “Sapphica . . . musa doctior” (“more learned . . . than the Sapphic muse”). In Mamie Gwinn’s course on the English essay concentrating on “Arnold, Pater and Swinburne,” she would have read Swinburne’s Notes on Poems and Reviews in defense of “the very words of Sappho.”

Thomas’s message to students at Bryn Mawr College was double: that women’s higher education should replicate the “quality and quantity” of men’s colleges, on the one hand, and provide women students with prototypes such as Sappho who could serve as transformative models for women of the future, on the other. Indeed the twofold nature of Thomas’s notions was written into the project of women’s higher education.

Specifically with regard to Greek learning, it was impossible for young women to embrace the discipline of philology in the neutral, unstressed ways of men, whose gendered lives as men were not changed by their access to Greek learning. At the very least, women made Greek learning a sign of their capacity for cultivation. This was no small matter, for by learning to read Greek at Bryn Mawr College as if they were men reading Greek at Harvard College, women showed their capacity both for doing what men were already doing and for assuming some of their roles. In this way, they were “invert[ing] the traditional privilege system that lends primacy to men.” They and their Greek books were implicated in a social transformation. “What didn’t the Greeks have?” Eva would later ask Natalie Barney, making the point that the Greeks gave her everything she needed to live a transformative life.

Eva embraced the contradictory directions given to her by Bryn Mawr College. Though no stellar student, she gained enough training in classical languages to understand the significance of gendered adjectival endings and pronouns (lost in English translation) and to recite Sappho’s poetry in ancient Greek. Then, following Thomas’s second line of argument, she made use of classical prototypes to invert social conventions. She was likely practicing some form of “inversion” in the sexual sense in her dormitory room in Radnor Hall in the spring of 1898—perhaps testing Sappho’s words of love on a fellow student. At least one female classmate, Virginia Greer Yardley, recalled having a devastating “crush on Eva Palmer” and remained emotionally attached to her for years. In any case, Eva was caught doing something strictly prohibited, and President Thomas wrote her a stern letter “[forbidding her] the right of residence in the halls of Bryn Mawr College for one year from the 28th of May, 1898, to the 28th of May, 1899.”

It was commonplace to believe that women might grow “unwomanly” or excessively free if they got too close to Greek learning. In Eva’s case, her accession to classical studies did bear something in excess of the anticipated outcomes of a college education. When she and her female friends exchanged Greek words in private moments, they were not just proving themselves to be “as fully classical as men.” These women were using the classical to renegotiate old gender and sex roles, circumvent the attendant taboos, and express new desires. They were pushing old Western cultural models onto unconventional ground as an unwelcome “heresy.” It was for some such unspecified heresy that Eva was suspended from Bryn Mawr in the spring of 1898 and traveled to Europe with her brother Courtlandt, who was studying piano in Rome.

__________________________________

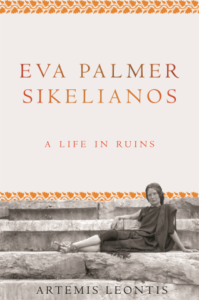

From Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins. Used with permission of Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Artemis Leontis.

Artemis Leontis

Artemis Leontis is professor of modern Greek and chair of the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Topographies of Hellenism and the coeditor of “What These Ithakas Mean...”: Readings in Cavafy, among other books. She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.