“It Can Be a Wild Story, but Everything Has to Feel Real.” A Conversation With Graphic Novelist Rutu Modan

The Author of Tunnels Talks to Jason Lutes

Rutu Modan (Tunnels, Exit Wounds, The Property) and Jason Lutes (Berlin) spoke to one another as part of D+Q Live, a fall event series by the graphic novel publisher Drawn & Quarterly. The driving force behind November’s conversation was Modan’s fourth English-language book, Tunnels, translated by Ishai Mishory. Lutes has said of Tunnels:

“Rutu Modan has written and drawn a true adventure story for the modern age, where a classic quest for precious antiquities is complicated by human relationships and real-world politics. Vivid characters vie for control, events take unexpectedly hilarious turns, farce folds in on itself, and a cow jumps over the moon.”

With Lutes zooming in from Vermont and Modan from Tel Aviv, their conversation touched on the utility of archeology for Zionists, how to draw the subterranean, and the kind of people who have a cliche for every occasion.

*

Jason Lutes: First of all, I love this book. It’s one of the most entertaining, engaging, funniest comics that I’ve read in years. It’s really wonderful.

Rutu Modan: Hearing it from you, it’s really a compliment.

Jason Lutes: Having tried to write a longer-form book myself with a broad cast of characters, I would really love to hear what the initial seed of the idea was, where it came from.

Rutu Modan: After finishing The Property in 2013, a conversation with a friend reminded me of a story that I heard in my twenties. A classmate I met at the Academy of Art in Jerusalem, together with his father, had dug illegally looking for the Ark of the Covenant. They did this for a few years, his father even took him out of high school to help. Of course, they didn’t find anything. At the time he told me this, it was just a joke. Then, when I suddenly remembered the story, I asked myself for the first time: “Why did they do it?” I knew the family quite well. I knew the father, and they were not religious. They’re not mystical people, just, more or less, regular people. So, it made me think: What is the connection? Why did they believe?

I was never interested in archeology before because in Israel, the findings are quite miserable. Not very interesting… but the stories! So I started reading about it and found so many great things connected to it: history, crime, money, obsession.

I also started to think about and understand how archeology was used by Zionism to justify itself. And I understood the connection with current politics. I’ve always been interested in the connection between past and present and how regular people and their daily lives are influenced by things that happened a really long time ago.

JL: One of the most striking things about Tunnels is the cast of characters. A pretty big cast, and each one of them very distinct. Part of the pleasure of reading the book is seeing how those personalities interact and clash or mesh with each other. We have here a cast of real individuals who are funny, with all the flaws of real human beings. I would love to know how you came up with this wonderful group of people.

RM: This is one of the reasons that it took me so long to write this book. The Property has five characters. And here you have 20, each with their own story arc. In a way, the book was just an excuse for me to show Israeli society as I see it. When I write, I also think about people that I know. And each of them, maybe, is connected to someone that I know.

JL: There’s a cast list at the back where you have actors listed. Did you use them for photo reference?

RM: Because of the way I write, I don’t use captions (for narration) much, and I never write what people think. I want the reader to understand the characters through their actions and words. The combination of how they act and what they say, which sometimes contradicts. Comics is a great medium to reveal that contradiction because a comic is made up of pictures and text.

After I finish the script, I storyboard the whole book to plan all the panels and what exactly will be in them, but it’s not very beautiful. Then, I hire professional actors. I direct them according to the panels. I used to model for myself or ask friends. But actors, they have this talent. This is what they do. They have so many ideas about how to use their body and face to express themselves, to show what they think. I plan beforehand and know exactly what I want from them, but they also have flexibility: they can invent, express their ideas, and how they see the character. It was wonderful to invite these people to work on this book with me.

JL: There’s a collaborative aspect to it, which is so wonderful.

RM: Which is rare for a comic artist.

JL: Very much so. Do they perform in an actual setting or do you add the backgrounds later?

RM: Everything is in my studio. When I hire the actors, I tell them, “Okay, come, participate. You don’t have to learn anything by heart. You don’t have to read a script before. Just come on a certain day. I’ll take your photos.” And I shoot it like a movie in the sense that it’s not in the order of the scenes. Sometimes they don’t even know what the story is about. After a few days, they start to understand the character, what’s going on. It’s a lot of fun. I love it. It’s amazing working with other people.

JL: That’s such a great and novel approach. I think that other cartoonists in history have done similar things, but not to this level, at least in my experience. That explains in part why these characters have such distinctive personalities. You’re really paying attention to actual human beings and how they’re talking and relating to each other.

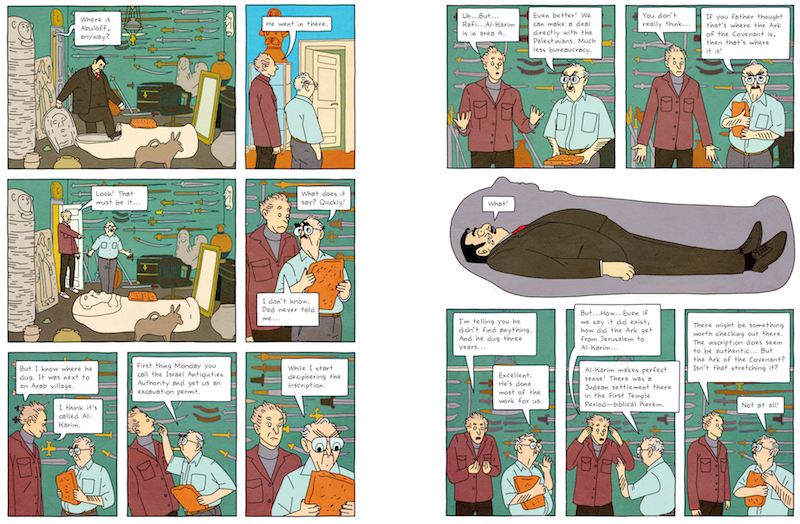

In this sequence, we have Abuloff, the collector, who is hiding in a room from these other two characters, who he wants to overhear.

He climbs into the sarcophagus, which is such a weird, idiosyncratic, goofy thing to do. I don’t feel any other character in the story would do that. It really feels specific to him. And then we get to see him sweating on the inside as he’s listening to this information being revealed. So, for me, that was a great little bit of character acting that this person was doing.

And Gedanken is such a character. He’s always trying to get some leverage or make it happen or have things go his way, and he is constantly quoting scripture. Are all of his quotes actual words from a holy book?

RM: Yes. I didn’t invent anything. In Hebrew, most of what he says are cliches. Israeli readers, even if they’re not religious, will recognize most of the phrases that he uses.

JL: You’ll be happy to know that even in translation, Gedanken’s quotes do come off that way. It comes off like, “Here, I have a little cliche for every occasion.”

So, you do all of the thumbnails. You stage it. It is like a little film. It very much feels like every location is a real location, too. They’re not just backdrops. They’re in physical places that have elements to them, which become a part of the story.

RM: I also looked for locations. Usually, when I draw the location, I am looking for the atmosphere, especially here. Another challenge is that most of the book takes place in the West Bank. I hadn’t gone before, for many years, because I was boycotting it. But because I had to draw it, I had to go, and look for the place where the story could take place.

I also thought of colors. What are they? What are the trees? How does it look, and how does it feel? Usually, my books are very urban. They take place in cities and houses. But suddenly I had to draw a landscape, this was a new interesting challenge. How do I draw nature? And especially, the West Bank, which is a landscape without trees. Most of it is small bushes.

JL: How did you figure out the camp, did you research? Because it also feels very real. There’s a laundry basket with food in it. There are all these little details, and the specific equipment that they’re using.

RM: This is something I have to do first for myself. I have to feel that it’s really happening. And it can be a wild story, but everything has to feel real. So I went to see an archeological dig, what is the equipment, what do they take with them? I thought about what they have to eat. Probably they have some kind of a kitchen. And they have to drink, so they have a water tank. I like to think about practical things. The big picture might be digging for the Ark of the Covenant, but you still have to eat and you still have to sleep.

JL: Was the book drawn digitally? I imagine you’re sort of combining it, compositing it somehow, and then drawing over it.

RM: Yes, it’s digital. If I miss something, I invent it or look for a reference. When I started this book, I said, “Okay, this time I’m going to be a minimalist.” I was very jealous of minimalist cartoonists, but I guess I can’t do it. I love drawing all these details. This is the fun part. It’s a lot of work, but it’s nice. It’s like going on a long vacation for me, just drawing because everything is already there. I have the story. I have the storyboard. Things are changing, of course, throughout the process, but still most of the time it’s drawing and drawing and drawing. It’s very fun to do. Just moving your hands for hours like this.

There’s all kinds of ways to feel empathy for these different characters.

JL: At what stage are you thinking about the colors? At what point in your process does the palette of a scene come in? Do you do all of the linework and then start thinking about colors or… ?

RM: Because it’s such a big project, I cannot think about everything at once. I focus on what I’m doing at any given moment. If I’m writing, I just think about writing. Not how I’m going to draw it because that’s too frightening.

JL: I can relate.

RM: Then the storyboard or directing the actors. And so, I do all of the linework, and after that, I color everything. And coloring is a big thing for me. First of all, it’s information.

It’s part of the storytelling and part of the rhythm of the story. Each scene has a very distinct color palette so that the reader will feel that it is a new place, new location, and new time. And they know this without thinking about it. Immediately, it’s like a cut in a movie.

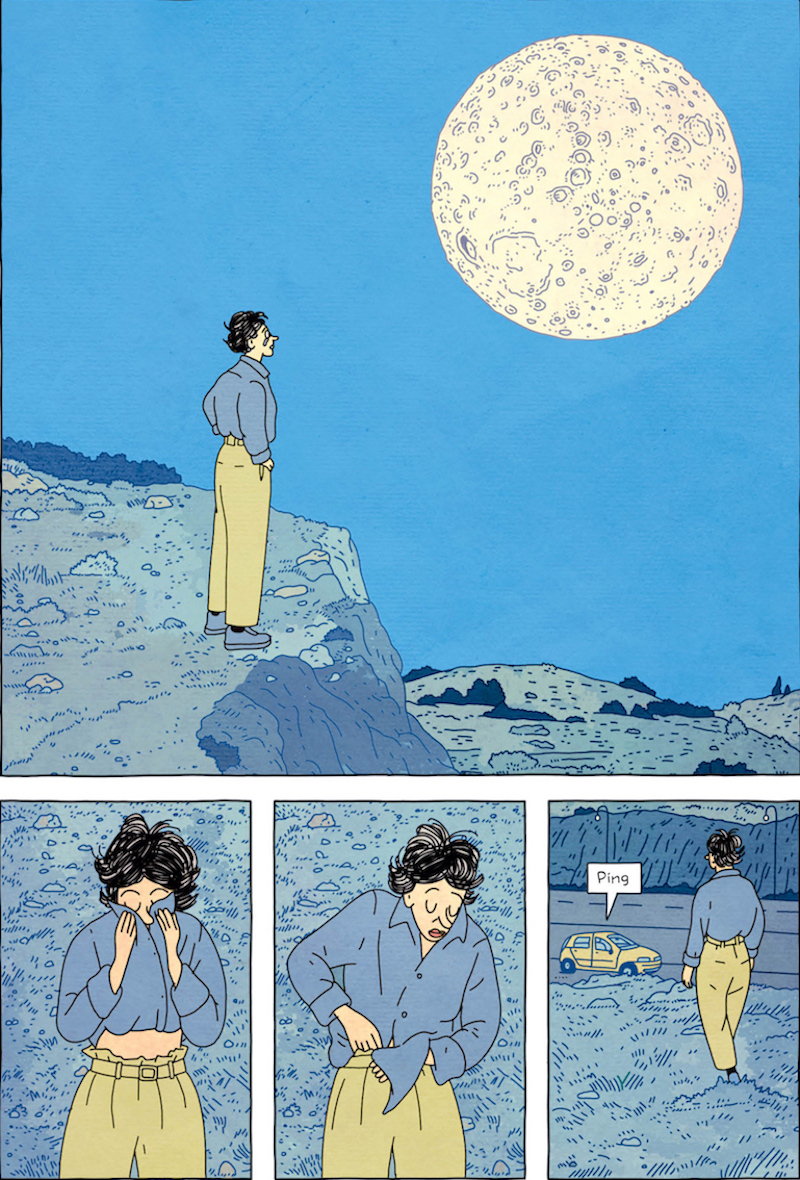

JL: This page right here is a great indication. It’s a moment where Nili is in a different mental state than she’s been in for a lot of the book and the colors convey that.

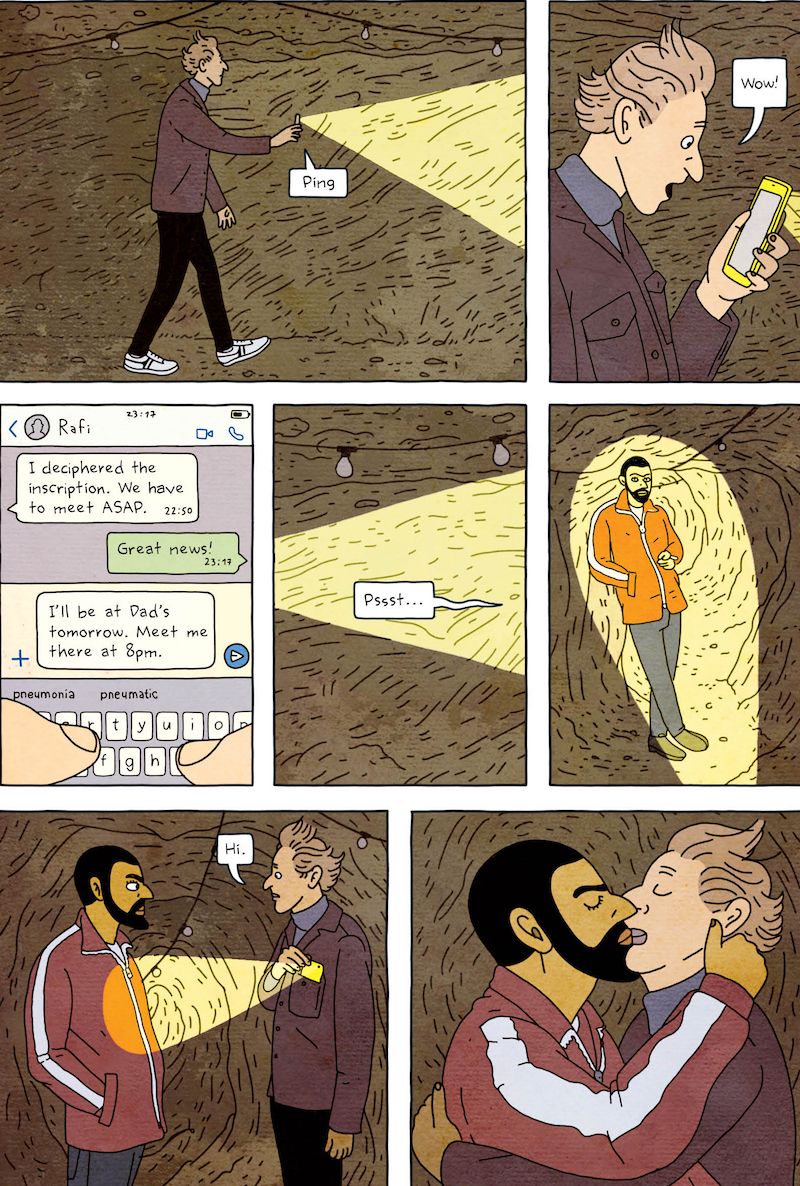

RM: There was another challenge for me as an artist. A lot of the book takes place in darkness, either underground or at night. So, I had to invent ways to draw night or to draw darkness. And how bright can it be because you have to see it. I needed to play with different levels of darkness. So I was constantly asking myself, how do you color night, but still make it colorful?

JL: Overall to me the book feels like a caper. It feels very funny. I was laughing out loud at some of the things these characters did, and I never do that in a comic. But it’s also like you said, a specific commentary on certain aspects of Israeli culture. There’s all kinds of ways to feel empathy for these different characters. There’s a tragic component to it. There was even romance, right? There is subterranean romance going on as well.

RM: A bit of romance. Yeah. I must have at least one kiss in each book.

JL: That’s one of your requirements? That’s great.

RM: When I wrote Tunnels, I wanted my protagonist Nili to have a romance. But Nili is not interested in love. I think about the women characters for my three big books. Numi in Exit Wounds, she was very conscious about her femininity. And Mica in The Property, she was beautiful, and she was very comfortable with it. But I think Nili’s not interested in her femininity. She has other things on her mind. She has no time.

JL: Thank you so much for sharing your process with us. I personally have been totally interested in how you go about making comics, and every cartoonist has their path that they take because this medium is still wide open and ready for exploration and people to discover how to make things on their own.

Your work is such a great example of that because it has a lot of the conventional: there’s panels on a page, there’s words and images arranged carefully on each page. But the way you’ve described your approach, the organic beginnings of the story, the way you respond to it as it’s in your hands, and then how the characters become a part of the world that you’ve created is… It could only have come from you. This is a singular kind of artistic approach, and the results are really wonderful.

RM: Thank you very much for this conversation.

__________________________________

Tunnels, translated by Ishai Mishory, is available from Drawn & Quarterly.