Isn't Every Narrator an Unreliable Narrator?

So Many Damn Books with Christopher Hermelin and Drew Broussard

On So Many Damn Books, Christopher Hermelin (@cdhermelin) and Drew Broussard (@drewsof) discuss reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never, ever dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in their hands!

This week, after reading Ian Parker’s “A Suspense Novelist’s Trail of Deceptions” piece from the New Yorker, Christopher and Drew get into unreliable narrators and what they hold (or hold back), and wonder if maybe every narrator is an unreliable narrator.

Drew Broussard: I was thinking a lot about the balance between art and life, and I was reading that Dan Mallory piece and I picked up this book The Hunting Party by Lucy Foley. It’s a mystery with a couple points of views and you can’t be sure if you can trust any and the ones you thought you can trust are the ones you can’t trust. They are thousands of books like this, but I got me thinking about how pervasive it is, this unreliable narration thing.

Christopher Hermelin: We lost so much faith in our narrators, but we never really had it. 18th-century literature, like Robinson Crusoe, it starts with sign-off that this is all really real and there is a newspaper article to illustrate this all really happened. It had to be a journal; it couldn’t be a straightforward novel because it’s more realistic.

DB: Dracula, too. All these books that are meant to feel like real texts.

CH: Exactly. We didn’t trust the narrator back then, so what if we tried to make you trust them even more. Now we can even destabilize a narrator as it goes, like Paula Hawkin’s Girl on the Train where the main narrator is an alcoholic. That’s the whole point: how much can you trust what she’s saying? I can understand why it was so exciting to see and pulled to the forefront like that. Of course, it’s behind a million other things that people love. When it’s done really artfully, it’s really exciting.

DB: Right, those books where you suddenly realize what you believed for fifty to eighty percent of the book is no longer true.

CH: Or that one detail they chose also explains away three other things they didn’t say. I was thinking about in particular Ottessa Moshfegh’s Year of Rest and Relaxation that has characters who you can’t trust what they’re saying because they’re under some sort of influence, and you hear one thing from them and another character will give you a detail where you’re not seeing how that happens. That’s when it gets really exciting for me, where a detail kind of shows off a shadow.

DB: Do you see out this kind of storytelling? I feel like every once in a while when I really want escapism I just want to churn through something in two days. I’ll pick up a mid-list thriller, I’m in it, I want to know what happens, it’s done and I’ve forgotten about it.

CH: It’s a page-turning thing. As you’re picking out details, you’re also realizing more and more you’re going to be revealed what is. They’re going to point it out and outline it for you, which is exciting because you’re going to get more and more of the pieces by the way around it. I do like that, but I like it more in the Donna Tartt way.

DB: More literary fiction, unreliable narrator and less solving a mystery together?

CH: I like The Secret History where the narrator of that likes aesthetics. He’s trying things, making things sound lavish more than they are. Or Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter. You wouldn’t say that’s a book about an unreliable narrator but I start to really get into the idea of what’s fact and what’s fiction of this and what’s the truth that they’re getting at. You know, in the way all fiction is science fiction because you’re making up the rules of your universe no matter what. Every narrator is an unreliable narrator because you have to choose the details that are going to explain your story.

*

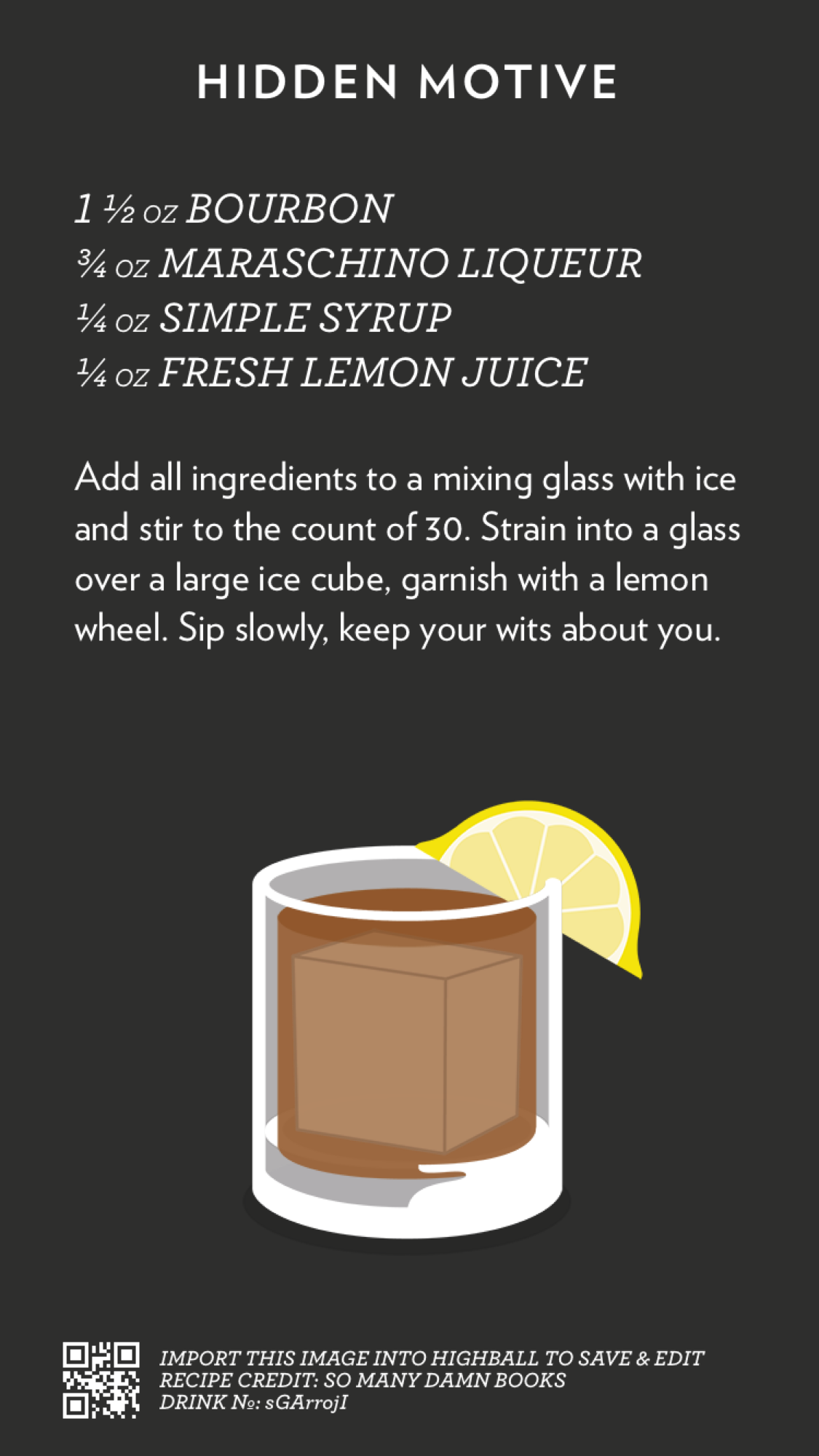

This week’s themed drink recipe:

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.