Isaac Bashevis Singer on the Particular Wonders of Writing

in Yiddish

An Iconic American Writer on an Oft-Misunderstood Language

I once said that a Yiddish writer is like a ghost who can see but is not seen. Perhaps that is why I like to write “ghost” stories. The Yiddish writer not only belongs to a minority but he is a minority within a minority. He is a paradox to his own people. Theoretically, a Yiddish writer is dead. He moves around like one of my phantoms, a corpse who either ignores his own death or is not yet aware of it.

When I tell people what my occupation is, I expect them to shrug. And they do. I feel no insult when asked, “Does Yiddish still exist?” Or when I am solemnly informed that I am writing in a dead language. In truth I have written in two “dead” languages. Forty years ago, the Hebrew I was attempting to write in was considered dead. In heder I also studied Aramaic, another dead language. These dead tongues taught me one lesson: when it comes to language, the difference between life and death is negligible.

I have witnessed in my lifetime the resurrection of Hebrew. Yiddish too has grown almost overnight from a primitive tongue to a language immensely rich in idiom, imagery, and symbol. In my own time, Ukrainian, Belorussian, Lithuanian, Latvian, and many other tongues and dialects in Asia, Africa, and South America have sprung to life. We are living literally in an epoch of the resurrection of languages. The world forgets or pretends to forget that many languages today, which are the pride of those who speak them, were once looked down upon, as Yiddish is at present. They too were called vulgar tongues. In the early Middle Ages, Latin and Greek were the languages of the intellectual, and English, French, German, and Italian were a kind of Yiddish, spoken by peasants. As late as the nineteenth century, the nobles of Russia and Poland boasted of their children’s ignorance of their mother tongues. French was the fashion then, even though this borrowed tongue failed miserably as a means of literary expression in the countries that had adopted it.

The Yiddish writer, I believe, is richer in topics and themes at his disposal than writers of any other modern tongue.

Many writers rose to greatness along with the languages that they helped to form. Pushkin, Dante, and Shakespeare did much to help create modern Russian, Italian, and English. Yiddish, although it was already spoken in those times, has been a few hundred years late in awakening. Modern Yiddish is only a few years older than I am. So rapidly have the changes come about that the language of books written in the beginning of this century are already somewhat obsolete. Even today, Yiddish still lacks a standardized spelling. The first Yiddish encyclopedia and a complete Yiddish dictionary are only now in the process of preparation.

This late maturing, however, carries with it some advantages. By writing in Yiddish, one is actually helping to establish the language. One chooses and polishes words extracted from an immense treasury of linguistic raw material. The Yiddish writer, I believe, is richer in topics and themes at his disposal than writers of any other modern tongue. Yiddish to him may be a literary Siberia, but one that is rich in virgin soil. It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that the Jew began in earnest to develop a secular literature. The Jewish fiction writer has had no time to exploit the vast subject matter offered by our history. As a source for fiction, even Jewish contemporary life has barely been touched. Jewish life, whether in Russia, Poland, Israel, or anywhere in the world, because of its very dispersion and variety, is a literary mine of inexhaustible potentiality. To the humanist, Yiddish has the distinction of being perhaps the only language never spoken by men in power. There are few words in Yiddish for weapons, the paraphernalia of war, and even hunting.

Among the nations of the world, the life of the Jew was and remains a unique adventure. We are the only people who, after being driven from their land, have retained their identity for two thousand years. We are the only people to return to a land from which they were exiled two thousand years ago. We are the only group to retain its original culture over such a long period. The Jew’s history is incredible. His very existence is an exception to the laws governing groups and cultures.

Since this article is not intended as a lesson in sociology or literature, I will now make a few remarks about myself. It may sound strange, but I happen to be an exception among the exceptions. The other exceptions refuse to accept my membership in their ranks.

It is not easy to speak a “freakish” language, to belong to an exceptional people, and to be part of a literature whose legitimacy is openly suspect.

Modern Hebrew and Yiddish literature, emerging simultaneously and created by practically the same writers, were nothing less than an adventure of the spirit, but those who created them were unconscious of their adventurous character. It may be that when, one day, the dead awake and emerge from their graves, they will not see their resurrection as unusual. They will as likely as not go about such practical tasks as finding their relatives and adjusting to the prevailing economy.

But in my case, I was born with the feeling that I am part of an unlikely adventure, something that couldn’t have happened but happened just the same. The atmosphere of adventure permeated my home. My paternal grandfather was a Kabbalist, my maternal grandfather was a religious philosopher, my father was a Hasid, my mother an anti-Hasid, my sister suffered from hysterical seizures, my brother, I. J. Singer, tried rebelliously to become first a painter and then a writer. It was the entire household, not only I, who looked upon the worldly past, present, and future as one big adventure. My father always related the miracles of famous rabbis. My mother refuted them, but she was herself possessed by an unusual curiosity about the supernatural. My sister behaved as though possessed by a dybbuk. My brother, who was supposed to be the family rationalist, saw with uncanny clarity the bizarre unreality of Jewish life in Poland. The astonishment that came over me when I began to read Jewish history has not left me to this day. What astounds me more than anything else is seeing a Jew who is not baffled by his own existence. In a sense the whole human race should marvel and wonder. What is humanity but an incredible adventure on this earth, or perhaps in the cosmos?

For me, the function of literature in general, and particularly Yiddish literature, is to record this perplexity of the spirit. But to my regret, I have found little of this sense of wonderment in world literature and, alas, almost nothing of it in modern Yiddish literature. With few exceptions, modern Yiddish writing preaches a worldly positivism. It attaches itself to causes that seem to me both narrow and problematic. It is indifferent to the dark depths and strange undercurrents of Jewishness.

I know that our literature could not have been exactly as I would have wished it to be. A sea serpent, if it lives somewhere in the ocean, searches for its food just as any other creature does. It does not think of itself as a monster. Nor does it worry that according to the zoologist it is nothing more than a legend. It is not easy to speak a “freakish” language, to belong to an exceptional people, and to be part of a literature whose legitimacy is openly suspect. I sometimes dread the professor who, after examining me to detect what type of specimen I am, will pronounce me a prehistoric animal or one of evolution’s embarrassing slips. I am often asked what I think about the future of Yiddish, and I hesitate to admit that I don’t really care. There are at least two thousand languages and dialects in the world that are spoken by even fewer people than Yiddish. Many of them are in danger of being swallowed by the linguistic whales. There must be a number of good writers and exceptional talents who remain forever undiscovered to the large world because of the obscurity of their mediums. Even if adequate translation were possible, their chances of playing the role they deserve in literature would remain at best precarious.

Writers have never had any guarantees as to the number of their readers or the future of their languages. Nobody can tell what will happen to the words and phrases in use today or five hundred years from now. Anew way of conveying ideas and images may be found that will make the written word, and perhaps even today’s spoken word, completely superfluous. It is not the language that gives immortality to the writer. The very opposite is true: great writers do not let their languages become extinct.

I am amazed to see other nations go through ordeals comparable in some way to those the Jews had to undergo. I notice how many “new” languages are confronted with the problems Yiddish has faced and is still facing. Not only Yiddish but all languages are constantly in the throes of death and in the terrible effort of being reborn.

Because of the great demand for fiction on the part of the publisher and reader, and nature’s small supply of genuine talent, producers of disguised journalism and pseudo-literature are taking over the artist’s place almost everywhere and particularly in the large civilized countries. Fiction writing is becoming a forgotten art. The epoch of literary barbarism and deliberate literary amnesia has already begun.

In some eerie way the predicament of the Yiddish writer is becoming the predicament of the serious writer all over the world. The uncanny power of the cliché and mass production may drive all creative writers into a corner and may actually excommunicate the writer who refuses to adjust himself to the caprices of vast audiences and the economy of publishing. It has already happened in poetry. It is happening in drama. Serious fiction is next. Literature in America is already divided into a small number of bestsellers and books that remain in obscurity, or at best semi-obscurity. The lot of Yiddish today may be the lot of genuine fiction tomorrow. I personally don’t look upon this as a misfortune. I have become accustomed to being a “ghost.”

__________________________________

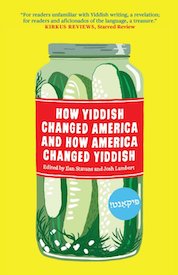

Excerpted from How Yiddish Changed America and How America Changed Yiddish (Restless Books, Jan. 2020). First published in Forverts (1965). Reprinted with the kind permission of the Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust.

Isaac Bashevis Singer

Isaac Bashevis Singer was a Polish-American writer who won the 1978 Nobel Prize for Literature.