Is There an Inherent Connection Between Sadness and Art-Making?

From Beethoven to Leonard Cohen, Susan Cain Wonders About Melancholy and Creativity

In 1944, when the poet-musician and global icon Leonard Cohen was nine years old, his father died. Leonard wrote a poem, sliced open his father’s favorite bowtie, inserted his elegy, and buried it in the family garden in Montreal. That was his first artistic expression. He would echo it again and again during his six-decade, Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award–winning career, penning hundreds of verses on heartache, longing, and love.

Cohen was famously sensual, romantic, a ladies’ man; Joni Mitchell once called him a “boudoir poet.” He had a hypnotic baritone, a shy charisma. But none of his love affairs lasted; as an artist he “existed best in a state of longing,” as his biographer Sylvie Simmons put it.

Perhaps his greatest love was a Norwegian beauty named Marianne Ihlen. He met her on the Greek island of Hydra in 1960, where a free-spirited international arts community had formed. Cohen was a writer then; it wouldn’t occur to him to set his poetry to music for another six years. Every morning he worked on a novel, and in the evenings, he played lullabies for Marianne’s son by another man. They lived in domestic harmony. “It was as if everyone was young and beautiful and full of talent—covered with a kind of gold dust,” he said later of his time on Hydra. “Everybody had special and unique qualities. This is, of course, the feeling of youth, but in the glorious setting of Hydra, all these qualities were magnified.”

But eventually Leonard and Marianne had to leave the island, he to earn a living in Canada, she to Norway for family reasons. They tried to stay together but couldn’t make it last. He moved to New York City, became a musician, was swept up in a scene that never really suited him. “When you’ve lived on Hydra,” he said later, “you can’t live anywhere else, including Hydra.”

He moved on with his life, Marianne with hers. But she inspired some of his most iconic songs—about leave-taking. They had titles like “So Long, Marianne” and “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” “There are some people that have a tendency towards saying hello,” Cohen said of his music, “but I’m rather more valedictory.” His last great hit, released three weeks before his death at age eighty-two, was called “You Want It Darker.”

Sad moods tend to sharpen our attention: They make us more focused and detail oriented; they improve our memories, correct our cognitive biases.

Even those who adored his work commented on its somber nature. One of his record companies joked about giving away razor blades with his albums. But that’s a limited way to think about him. He was really a poet of dark and light—of the “cold and broken Hallelujah,” as he put it in his most famous song. Whatever pain you can’t get rid of, he seemed to say, make it your creative offering.

Is creativity associated with sorrow and longing, through some mysterious force? The question has long been posed by casual observers and creativity researchers alike. And the data (as well as Aristotle’s intuition, per his question about the prominence of melancholics in the arts) suggest that the answer is yes. According to a famous early study of 573 creative leaders by the psychologist Marvin Eisenstadt, an astonishingly large percentage of highly creative people were, like Cohen, orphaned in childhood. Twenty-five percent had lost at least one parent by the age of ten. By age fifteen, it was 34 percent, and by age twenty, 45 percent!

Other studies suggest that even creatives whose parents live to their dotage are disproportionately prone to sorrow. People who work in the arts are eight to ten times more likely than others to suffer mood disorders, according to a 1993 study by the Johns Hopkins psychiatry professor Kay Redfield Jamison. In his study of the artistic psyche, Tortured Artists, a 2012 book profiling forty-eight creative outliers from Michelangelo to Madonna, author Christopher Zara found that their life stories share a certain amount of pain and suffering.

And in 2017, an economist named Karol Jan Borowiecki published a fascinating study in The Review of Economics and Statistics called “How Are You, My Dearest Mozart? Well-Being and Creativity of Three Famous Composers Based on Their Letters.” Borowiecki used linguistic analytic software to study 1,400 letters written by Mozart, Liszt, and Beethoven throughout their lives. He traced when their letters referred to positive emotions (using words like happiness) or negative ones (words like grief ), and how these feelings related to the quantity and quality of the music they composed at the time. Borowiecki found that the artists’ negative emotions were not only correlated with but also predictive of their creative output. And not just any negative emotions had this effect. Just as scholars of minor key music found that sadness is the only negative emotion whose musical expression uplifts us (as we saw in chapter 2), Borowiecki found that it was also “the main negative feeling that drives creativity.” [Emphasis added.]

In another intriguing study, Columbia Business School professor Modupe Akinola gathered a collection of students and measured their blood for DHEAS, a hormone that helps protect against depression by suppressing the effects of stress hormones such as cortisol. Then she asked the students to speak to an audience about their dream jobs. Unbeknownst to her subjects, she arranged for some of these talks to be greeted supportively, with smiles and nods, and others with frowns and head shaking.

After the talk, she asked the students how they were feeling; unsurprisingly, those with receptive audiences were in a better mood than the ones who thought they’d bombed. But she also asked the students to make a collage, which professional artists later rated for creativity. The students who faced disapproving audiences created better collages than the ones who were smiled upon. And those who received negative audience feedback and had low levels of DHEAS—that is, the students who were both emotionally vulnerable and suffered rejection from the audience—made the best collages of all.

Other studies have found that sad moods tend to sharpen our attention: They make us more focused and detail oriented; they improve our memories, correct our cognitive biases. For example, University of New South Wales psychology professor Joseph Forgas found that people are better able to recall items they’ve seen in a store on cloudy days compared to sunny ones, and that people in a bad mood (after being asked to focus on sad memories) tend to have better eyewitness memories of a car accident than those who’d been thinking of happy times.

There are many possible explanations, of course, for such findings. Perhaps it’s the sharpened attention that Forgas’s studies suggest. Or maybe emotional setbacks instill an extra degree of grit and persistence, which some people apply to their creative efforts; other studies suggest that adversity causes a tendency to withdraw to an inner world of imagination.

It’s not that pain equals art. It’s that creativity has the power to look pain in the eye, and to decide to turn it into something better.

Whatever the theory, we shouldn’t make the mistake of viewing darkness as the sole or even primary catalyst to creativity. After all, plenty of creatives are sanguine types. And studies also show that flashes of insight are more likely to happen when we’re in a good mood. We also know that clinical depression—which we might think of as an emotional black hole obliterating all light—kills creativity. As Columbia University psychiatry professor Philip Muskin told The Atlantic magazine, “Creative people are not creative when they’re depressed.”

Instead, it may be more useful to view creativity through the lens of bittersweetness—of grappling simultaneously with darkness and light. It’s not that pain equals art. It’s that creativity has the power to look pain in the eye, and to decide to turn it into something better. As Cohen’s story suggests, the quest to transform pain into beauty is one of the great catalysts of artistic expression. “He . . . felt at home in darkness, the way he wrote, the way he worked,” observed Sylvie Simmons. “But in the end, it really was about finding the light.”

__________________________________

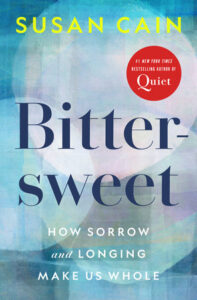

From Bittersweet by Susan Cain. Copyright © 2022 by Susan Cain. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Susan Cain

Named one of the top ten influencers in the world by LinkedIn, Susan Cain is a renowned speaker and author of the award-winning books Quiet Power, Quiet Journal, and Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking. Translated into more than forty languages, Quiet has appeared on many best-of lists, spent more than seven years on the New York Times bestseller list, and was named the #1 best book of the year by Fast Company, which also named Cain one of its Most Creative People in Business. Her TED Talk on the power of introverts has been viewed over forty million times.