Is the Past a Literary Genre Unto Itself?

Sophie Mackintosh Speculates on the Nature of Historical Speculation

On January 2nd, 2020, with no idea what to come, I started off the year by taking a long bus into central London, and then walked around a small art gallery where you had to take your shoes off. It was still as a cathedral, bathed in white light. I was the only one there for quite some time, observing small and perfectly-formed ceramic sculptures. It was a day that felt like a small miracle, clear blue sky and freshness, and I went afterwards to a nearby cafe and sat and wrote the first sentence of what would become Cursed Bread.

I have always loved that moment, the plunging into possibility, and this time I felt an extra edge of excitement, because I was striking out into what felt like vaguely uncharted territory. My previous two novels had tended towards the speculative, but this time I was working from the seed of a fact—a real-life case of a mass poisoning in South France—and so branching out, technically, into historical fiction.

One night during the summer of 1951 in the town of Pont St-Esprit, 250 inhabitants found themselves struck by terrible hallucinations; seven died, while more were committed to asylums. The tragedy had taken hold of me ever since I had happened upon the story, due to its strangeness, and due to the theories behind its cause.

The most likely theory is that the bread was contaminated by naturally-occurring ergot, but another theory is that it was part of a CIA mind control experiment, testing LSD on an unwitting population.

With this idea in mind, during the months of thinking about it two characters had come to the forefront for me; a charismatic and mysterious ambassador from the United States, and his wife, arriving into a quiet French town to set a plot in motion. And as I thought more about the role that bread would play in this plot, another character came to me too, this time of a baker’s wife, eager for something to puncture her monotonous days.

I believed the process of writing the novel would be easier, based as it was on a true story. In my previous novels, The Water Cure and Blue Ticket, I invented entire worlds and set pieces—one a claustrophobic island kingdom, the other a sepia-tinted strange universe of roads and mountains and service stations, where the rules we knew were warped.

I can’t help but feel there is a nobility in exhaustive research.

This time, I told myself, I wouldn’t have to do so. This time I was working from fact, from a kind of framework, or at least I believed I was. In retrospect, this was naive. Part of the frustration and fun of writing is the not-knowing until the words are on the page whether they will bear weight, ring true. This complacency—it’s a story pretty much written already, we know how it goes—was quickly dispelled.

Sometimes I wonder if it would have been dispelled, veered so far into something else, if it hadn’t been for the circumstances in which it was written. I worked solidly through January and February, looking forward to a residency in Paris planned for March, from which I would travel to the town itself.

But as the news started to roll in, and my residency was cancelled, I realized the process of writing from fact was going to go much differently to how I had imagined it. There would be no strolling around the streets where history had taken place, taking in the atmosphere, learning first-hand.

Instead there was sitting at a desk during an unseasonable spring heatwave, hovering my cursor over Google Maps, reading what I could find about the catastrophe, claustrophobia setting in as my ideas of what a historical novel could or should be shifted before my eyes.

My experience of novel-writing has always been that the heart of thing never really makes itself apparent right away. Even when you have everything planned out scene to scene, that when it feels like you know exactly how it will go, novels have a habit of spooling out. One tangent embarked upon can quickly become a new direction, the spark that alights the whole process.

One such tangent gave me the insight that the novel was not necessarily about the poisoning, but about how we ourselves can be poisoned by not-knowing, by losing our grip on reality, by falling into obsession. Suddenly the carefully-planned scene list, the obedient working through to an ending that felt ordained, needed a new approach.

Is all historical fiction not a branch of speculative fiction, after all? I reasoned to myself, in that hot room, over that rickety table, in the feverish and pent-up state that characterized my writing of it. Maybe it was better this way, to not feel tied to fact, to not know the exact shape of things. Writing as I was about memory, about trauma, this flexibility felt particularly fitting. And this was a real tragedy, after all; to retell the exact details in gory detail with the dispassionate eye of an observer started to feel intrusive.

So in this way it became not the town of the tragedy but a more theoretical town, a space beyond history, fable-like and inexact. It became the hyper-real idea of a pastoral French setting, thick with textures, a site where the strange could happen. It became a town as remembered during one febrile, terrible summer by one person, Elodie the protagonist, necessarily subjective, colored by her desire.

I saw the summer I was writing it in reflected—the world turned upside down, the heat, the collective grief. I realized, near the end, that I hadn’t even mentioned the name of the town. It had become something more than itself, the story a springboard, something I had run away with.

One of my favorite recent novels has been Briefly, a Delicious Life by Nell Stevens, a fictional retelling of the summer writer George Sands spent in Mallorca with Chopin in the 1800s, narrated through the point of view of a teenage ghost who falls in love with her. I loved this interpretation of events, this inhabiting beyond historical details; another springboard with which to move into fiction, into the possibilities of story.

I read it after I finished the edits for Cursed Bread, slung across sun-warmed rocks on the shores of the Adriatic, and realized that in allowing ourselves the freedom to imagine beyond fact, we also allow ourselves possibility, and we allow ourselves a kind of fun. We are not tethered to our world, but can dip into another.

I’ll admit that at times I have worried that this leaning into the freedom and relief of being unable to know the exact details, this embracing of the inexactitude of history, of composite settings and subjectivity, can veer towards lazy. I can’t help but feel there is a nobility in exhaustive research, in discovering the exact grain of the exact fabric that someone would wear in an exact decade three hundred years ago, in melding these tiniest details with our own imaginations.

But then I think about how in my more outwardly speculative novels I have shied away from tying myself too tightly to tropes, preferring to take what I wanted and leaving the rest; there is little world-building, for example, and there is plenty of space around the images and words for readers to reach their own conclusions, their own takes on events.

There is a joy in picking and choosing the parts that feel right for the story you are trying to tell, for the trick you are attempting to pull off. And why not? In speculation, we aren’t limited. You can take fiction anywhere, and actually we so rarely do. We write differently, with our own approaches, and three novels in I am accepting that I will always be pulled back to this space of possibility, where reality and fantasy feed into each other, live happily side by side.

__________________________________

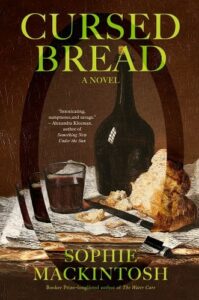

Sophie Mackintosh is the author of Cursed Bread, available now from Doubleday.

Sophie MacKintosh

Sophie Mackintosh is the author of Blue Ticket and The Water Cure, which was longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize and won the 2019 Betty Trask Award. In 2016 she won the White Review Short Story Prize and the Virago/Stylist Short Story competition. She has been published in The New York Times, Elle, and Granta magazine, among others.