Is Space the Final Frontier of Espionage?

Anthony Vinci on Space Warfare, Spy Satellites, and Science Fiction Becoming a Reality

The greatest explorers have also been great spies. The two professions are intimately linked, with both spies and explorers illuminating the unknown. People like Sir Richard Francis Burton exemplify this connection. Burton’s exploits and intellect are legendary. He spoke twenty-nine languages and led an expedition to Africa in search of the source of the Nile, becoming the first European to see Lake Tanganyika.

But he was also a soldier and a spy, reporting back to the British Empire as part of the Great Game with the Russian Empire in Central Asia. Empires and nations need both maps and reports from the field. They must prepare for military contingencies or be able to make diplomatic decisions.

Indeed, my former agency the NGA is charged with both making maps (the job of explorers) and uncovering what’s really going on in those places (the job of intelligence officers). This interplay between exploration and espionage continues today, even when the surface of the world has been almost completely explored. Now we’ve moved on to space. The Space Race was not just about putting men into orbit or landing them on the Moon; it was also about putting up spy satellites.

Today, we are in the midst of a new space race, as the United States, China, and, to a lesser extent, Russia, India, and others put more and more satellites into orbit and push the envelope in exploration, from the Moon to asteroids to Mars and beyond. Intelligence follows this exploration and expansion, as it always has.

To see this race in action, just look up.

To see this race in action, just look up. On December 7, 2018, the Chinese launched Chang’e 4 (named for the moon goddess of Chinese mythology) into outer space and landed a probe, named Yutu-2, on the far side of the Moon. This rover explored parts of the Moon the Americans and Russians never had. After first landing in the Von Kármán crater, a 110-mile-wide divot, Yutu-2 employed radar to explore beneath its surface. Because the Moon blocks the transmissions from Yutu-2 to Earth, the Chinese rover used a relay satellite to communicate with its base back home. And during all this, the probe remained invisible to U.S. observation.

While most Americans certainly missed this story, our intelligence agencies did not. No doubt, they were immediately aware of Chang’e 4’s importance, not only for what it could do, but also for what its successful landing meant for our competition with China. Also frightening, the United States had no Earth-based means of tracking Yutu-2. Intelligence officers are a paranoid bunch, and they surely asked themselves what else our most capable competitor might be up to out there.

As the boundaries of exploration expand, so, too, does intelligence. The United States is already scrambling to learn what sort of space capabilities China has, what the CCP is building, and what China’s real intentions are. It’s not hard to imagine a future where clandestine intelligence and covert actions are undertaken on the Moon—if this isn’t happening already.

As things develop further, nations will spy on one another’s lunar satellites and bases, trying to see what they are working on and who is there. Indeed, as soon as someone reaches Mars and begins setting up semi-permanent or permanent facilities, we will certainly see espionage become multi-planetary. Space espionage is not new; what is new are the players, the scale, and the distance we will go.

The era of spy satellites began with the United States’ CORONA program, but just two years later, the Soviets launched their Zenit satellite program, which carried their cameras to capture pictures of Earth’s surface and U.S. military secrets. Just as we did with our secret CORONA program, the Soviets claimed that Zenit was being used for scientific exploration, though it was of course being used for intelligence-gathering purposes. The Chinese successfully launched their first spy satellite, the Fanhui Shi Weixing, in 1975. The CORONA program ran through 1972, and the Zenit program would operate into the 1990s. There were many more secret spy satellite programs on both sides, some of which continued to use film and, later, digital cameras, while others collected signals from antennas or other classified means.

Space espionage is not new; what is new are the players, the scale, and the distance we will go.

From those small, very secretive beginnings, space-based intelligence has become a cornerstone of intelligence. The National Reconnaissance Office, which oversees building and launching spy satellites, has a classified budget. While there is little information about the size of the NRO’s budget, the New York Times reported in 1994 that the budget was around $6 billion (around $12 billion in 2024 dollars).

It’s also safe to assume that budgets have gone up since then. On top of that, Space Force, the newest military service charged with organizing, training, and equipping personnel to protect U.S. interests in space, spent nearly $30 billion in 2024, and a large portion of that is devoted to intelligence. Space intelligence is big business.

By 2024, the U.S. government had around 170 civilian satellites and 250 military satellites in space. That may seem like a lot, but in that same year, around 10,000 satellites were operating in space in total, most of which were U.S. commercial satellites. Many of these commercial satellites are regularly used for intelligence purposes, as they collect imagery or other data that is then sold to intelligence agencies.

The future of space is commercial. It once took billions of dollars and thousands of people to put satellites and people into space, the work of a nation. Today, a high school team can put a tiny CubeSat into space for around the cost of a midsize car. That changes the game not only for space, but also for intelligence.

One company, the San Francisco–based Planet, designs, builds, and operates its own imagery satellites. The company was founded by former NASA engineers in 2010 and has since leveraged hundreds of millions in venture capital and, later, public market funding to launch more than two hundred satellites into orbit. Most of the Planet satellites are tiny (around a foot long), weighing less than eleven pounds. These satellites are launched on commercial rockets, and the images they take are beamed down to commercial satellite dishes around the globe. The images are then processed in Planet’s offices or in partnered analytical start-ups, where they are uploaded to the internet for anyone to purchase.

Today, a high school team can put a tiny CubeSat into space for around the cost of a midsize car.

This sort of commercial imagery has accomplished something truly new, something the CORONA engineers could only have dreamed about. In 2017, Planet developed a system to provide an updated photograph of the entire world every day. To put this into perspective, while CORONA photographed approximately 590 million square miles of the earth’s surface during its entire multiyear run, Planet photographs 186 million square miles every day.

Now it is possible to shift from analyzing imagery produced in a single location at a single time to viewing the constant change of the entire world. And rather than being designed in a Top Secret military facility—literally, Area 51, used for the U-2—at the expense of billions of taxpayer dollars, Planet’s doing it with around six hundred employees and hardly a security clearance in sight.

Nor is Planet alone. Other companies, such as BlackSky and Maxar, are providing their own electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) imagery—that is, images in the visible and infrared light spectrums—commercially. Moreover, it is not just EO/IR imagery that is now available. Commercial company HawkEye 360 collects and processes radio frequency data from its constellation of satellites using advanced algorithms. In other words, it does commercial space-based SIGINT—something many of us in the Intelligence Community never thought possible. Capella Space, Umbra, and ICEYE provide synthetic aperture radar satellites commercially—another improbability is that there is not just one but multiple commercial SAR companies in the world.

After years of balking, the Intelligence Community is now embracing this commercial turn. In July 2017, while I was at the NGA, we signed a $14 million contract with Planet to purchase its imagery. It was in many ways a challenge to the NGA not only to sign such a contract—we were already spending hundreds of millions of dollars per year on imagery from DigitalGlobe at the time—but also to figure out what to do with all this new imagery. The system simply was not set up to look at the entire world every day. More than that, it was not set up to work with nontraditional, often venture-funded tech companies that were dual use—that is, they had commercial products and ambitions beyond wanting to be government contractors.

Classified spy satellites are the Ferraris of the space world.

Since my time at the NGA, the Intelligence Community has turned more and more to commercial space. The NRO took over the mission of acquiring commercial space imagery from the NGA and now has multiple contracts out for EO/IR, SAR, hyperspectral, and other forms of space data amounting to over a billion dollars. The NGA continues to acquire analytics from commercial companies to figure out new ways to analyze this data, using AI and other new technologies.

Commercial imagery isn’t meant to replace the classified satellites; it is meant to be used alongside them. Classified spy satellites are the Ferraris of the space world. They are monstrous in size, highly intricate, and very expensive, but they do things no other satellites can. The term you often hear used to describe them is exquisite. They may have much better resolution or other highly classified features to better spy on adversaries.

More important, they are secret, their full capabilities unknown to those we spy on, making it hard for those adversaries to defend against or avoid their gaze. But they are very limited in number, and their information cannot be shared with anyone who doesn’t possess the highest of clearances.

Commercial satellites are much more inexpensive, much more numerous, and completely unclassified. This means they can capture more imagery at a lower cost, and that information can then be shared with anyone. With this imagery, a terrain map can be generated for use by urban planners, or a soldier can print a copy of an image and share it with foreign mission partners on the battlefield. This balance between the value of commercial capabilities and that of classified capabilities goes for many other types of “dual use” capabilities such as robotics or drones.

The biggest commercial space company of them all is SpaceX. Of the ten thousand–plus satellites in orbit in 2024, around six thousand were owned by SpaceX, part of its Starlink telecommunications network. Beyond satellites, SpaceX is best known for changing the game in launch with its Falcon 9, Falcon Heavy, and Starship rockets. These rockets were the first to be reusable and plunged the cost of a launch from ten thousand dollars or more per kilogram to around one or two thousand dollars per kilogram.

Eventually, they may get to one hundred dollars per kilogram, which starts being close to the price of a first-class airline ticket. This is a huge driver for bringing down the cost of the space economy in general and has been the opportunity for creating many other new space companies. Rocket Lab and other launch companies are doing the same.

But this is not just a commercial space race. War is also coming to space.

The secret to their success is in thinking about space and space vehicles in terms of manufacturing scale. Rockets and satellites were historically mostly built in massive, sterile places where engineers in Tyvek suits moved cautiously around intricate components. When I visited the SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, just south of Los Angeles International Airport, it was the polar opposite—a chaotic jumble of activity as former automotive engineers built rockets at breakneck speed. It felt like they were racing to get to Mars—which, in fact, they are.

SpaceX is also getting into the intelligence business. In 2021, under its Starshield business unit, it signed a $1.8 billion contract with the NRO. While the details remain classified, the goal is to build and launch a network of hundreds of spy satellites—or maybe more—with specialized intelligence payloads into low earth orbit. As one NRO spokesperson said, this Starshield-NRO collaboration represents “the most capable, diverse, and resilient space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance system the world has ever seen.”

The United States is not alone in this commercialization of space. The Chinese plan for space domination looks a lot like the way China came to control markets in 5G or rare earths. In 2014, the CCP opened the space sector to private capital, and in 2019 the China Commercial Space Alliance was launched to support that commercial growth both within China and globally. China’s space technology market is dominated mainly by the state-owned firms China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation and the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. It’s a safe bet that the CCP has already enacted a cyber intrusion and industrial espionage campaign to steal corporate and manufacturing information from the United States and space companies, including SpaceX.

At the same time, China is able to harness its manufacturing strengths to produce less expensive satellites and launch capabilities. The Chinese government can then subsidize these products for export through cheap central or provincial government financing. The space economy requires the same sort of economic intelligence as any other part of the economy to protect U.S. competitive advantage.

But this is not just a commercial space race. War is also coming to space. When President Trump first talked about plans for what became the Space Force, a new branch of the military designed to operate in outer space, some Americans thought it was a farce.

Late-night hosts cracked jokes, memes proliferated on the internet, and Steve Carell even starred in a Netflix sitcom about the Star Trek–like operation. But many in the government knew this was no laughing matter.

When, on December 20, 2019, President Trump announced the establishment of Space Force at a speech at Andrews Air Force Base, he noted that “Space is the world’s newest warfighting domain . . . Amid grave threats to our national security, American superiority in space is absolutely vital.” This is equivalent to the formation of the U.S. Air Force in 1947, which led to a massive ability to fight wars in the air—from the B-52 strategic bombers prepared to fight nuclear war, to the F-22 Raptor stealth fighter jets that still maintain air dominance, to fleets of MQ-1 Predator drones to surveil war zones around the world. The formation of this new military service is the biggest signal yet that the United States is preparing to deter wars in space and, in the worst-case scenario, fight them.

Where war goes, intelligence goes. The Space Force also created its own intelligence capability and became the eighteenth member of the Intelligence Community. This includes Space Delta 18, which acts as the National Space Intelligence Center; and Space Delta 7, which is the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance division of Space Force. Not long after, the NGA announced a change in its mission vision to note that it would “Know the World, Show the Way . . . from Seabed to Space.” The agency in charge of making maps and looking at Earth is now preparing to do the same for extraterrestrial bodies.

While tracking secret spaceships in Earth’s orbit may sound like science fiction, it is already a day-to-day reality, and the future of space is even more outlandish.

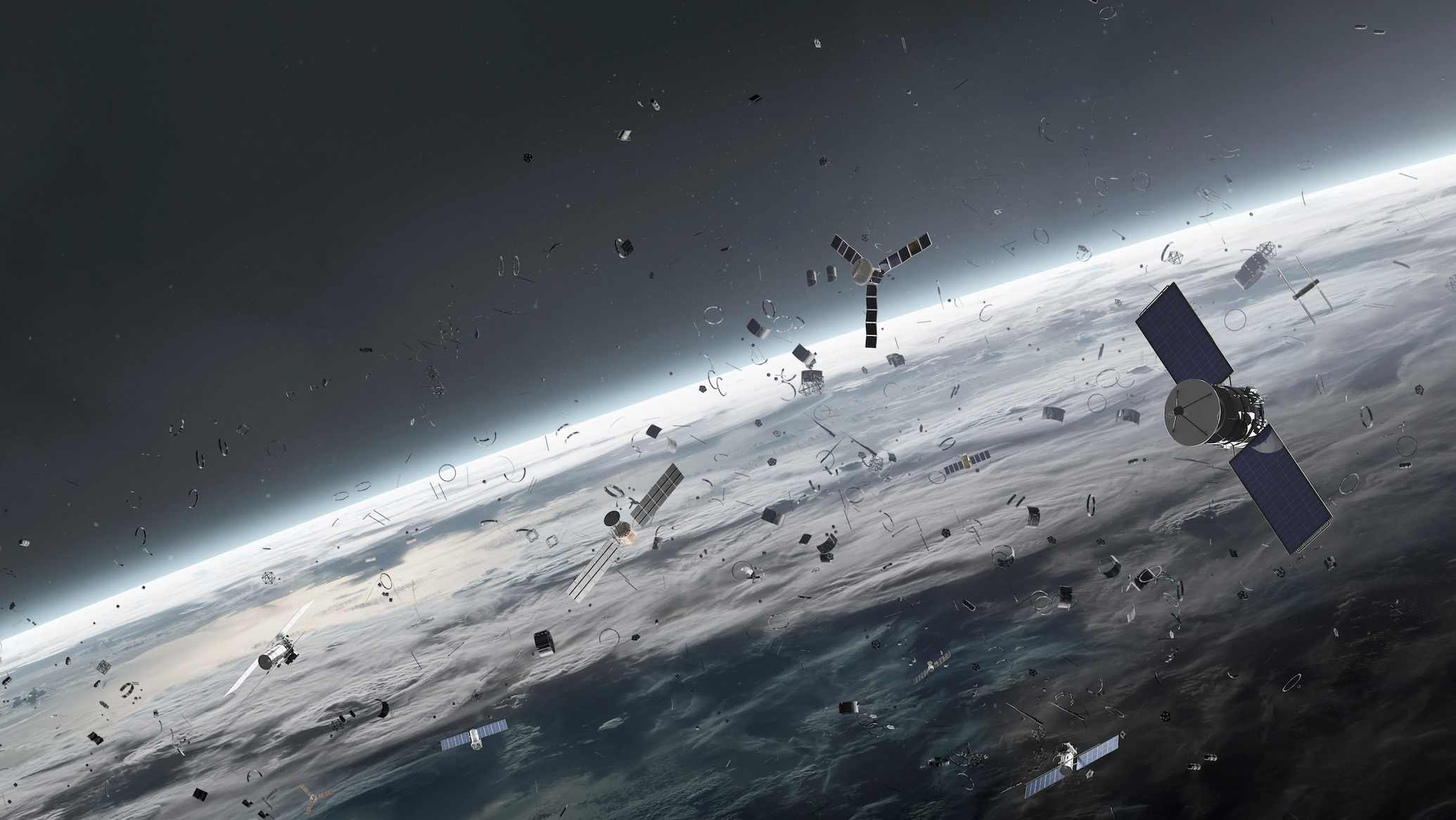

One key mission of the Space Force is space domain awareness (SDA), which is focused on tracking and monitoring objects in space. With increasing space traffic from various nations and private companies, keeping tabs on potential collisions and threats becomes crucial. Even small pieces of space junk (for example, leftover or broken pieces from space launches or nonfunctioning satellites) can have catastrophic effects. A softball-size piece of junk flying through space at 17,500 miles an hour could destroy a satellite or significantly threaten and potentially kill astronauts on the International Space Station.

Moreover, with space being a warfighting and intelligence domain, there is a need to track military and intelligence assets in space, just as we track adversary submarines, bombers, and secret reconnaissance overflights. SDA involves a network of groundand space-based sensors to create a comprehensive picture of what’s happening in Earth’s orbit. It is an innately whole-of-nation capability, with the Federal Aviation Administration and many commercial companies that provide data also playing major roles.

While tracking secret spaceships in Earth’s orbit may sound like science fiction, it is already a day-to-day reality, and the future of space is even more outlandish. By the mid-2020s, NASA’s Artemis program intends to return humans to the Moon. To complete this goal, NASA has teamed up with three companies, Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX, to design and construct aspects of the program. The goal is to create an operational Moon base. NASA has also let out contracts for building new Moon rovers and space stations, and some companies are already innovating in the areas of mining and construction on the Moon. Meanwhile, China and Russia have agreed to work together to create the International Lunar Research Station. The project aims to build a research base on the Moon for use by participating countries by the early 2030s.

The competition heating up between the United States and China, or the United States and Russia, will eventually expand beyond the Moon. Probes have already been sent to asteroids, and companies are planning to mine them for various precious minerals. The United States and, likely, China will send humans to Mars in the coming decades. And it’s probable that SpaceX or other companies will meet them there, or maybe even beat them there.

Once there is real activity on the Moon or an asteroid or Mars, there will be intelligence there as well. Telecommunications will be necessary on the Moon and other planets, just as they are on Earth. There might be radios used on the Moon’s surface and communications satellites around its orbit. If there is communication, someone will want to spy on that communication.

The United States and China will have bases and likely will want to keep some of the activities at those bases secret. So each nation will no doubt try to find out those secrets by using spy satellites or more secret means, like emplaced sensors. Even human intelligence will follow, as visual reconnaissance teams view what is happening in other settlements or try to recruit sources who live and work there. Intelligence has followed us from the Ancient Egyptians to today’s modern skyscrapers, and it will follow us to the stars.

Space intelligence expands the world of intelligence to the farthest reaches. This is not science fiction; it is real. But intelligence will also remain close to us; indeed, inside us. And that might feel even more like science fiction.

__________________________________

The Fourth Intelligence Revolution: The Future of Espionage and the Battle to Save America by Anthony Vinci. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2025 by Anthony Vinci. All rights reserved.

Anthony Vinci

Anthony Vinci served as the first Chief Technology Officer at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA). Earlier in his career he served in Iraq, Africa, and Asia. After leaving the world of intelligence, Vinci became an executive at a private equity firm and CEO of an AI company. He is an Adjunct Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) and received his PhD in International Relations from the London School of Economics.